South Carolina's farmland shrinking, number of young farmers dwindling. What is the industry's future?

Published in Business News

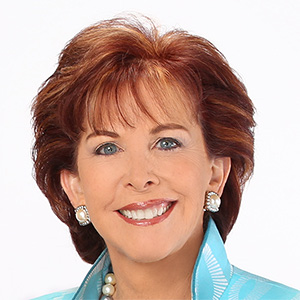

A little more than a stone’s throw from the Baptist church he grew up attending on Sundays, Troy Dobbins stops to feed his cattle with his wife, Taylor, and their 3-year-old daughter, Caroline, in tow.

“That one’s my favorite,” the youngest Dobbins tells her dad, pointing to one of the bulls in the field.

“What about Brownie?” Dobbins asks. “I thought Brownie was your favorite. Brownie’s getting a little round, looks like she might be ready to have her baby.”

On 100 acres of his family’s 600 acres of farmland in Townville, a rural, unincorporated community in Anderson County, the 31-year-old Troy is reviving his family’s legacy almost a decade after they left the dairy industry. Dobbins grew up the grandson of dairy farmers, in a family that had farmed since the ‘60s.

After Dobbins met his wife at Oklahoma State University, the pair spent a few years in Houston, Texas before moving back to South Carolina in 2020 and starting their cattle business with a handful of heifers.

But his example is an exception, not the rule.

Dobbins is one of few new farmers entering the agriculture industry in South Carolina. As younger generations of longtime farming families leave the industry and land becomes more unattainable, the average age of a farmer in the state is rising and farmland has been cut nearly in half over the last century.

“If it were up to me, do I think small farms and farmers should be around everywhere? Absolutely, but I can’t blame people,” said Jason Roland, a farmer with a small operation in Lexington County. “They inherit the land and then they sell it because they don’t want to do this and I can’t blame them for that because this is freaking hard.”

Across the state, even as generational family farms shutter or sell off land to developers, there are pockets of hope among younger farmers who are trying to keep the vital industry that puts food on tables afloat. They’re inventing new, creative approaches, changing the ways they do business and pushing younger people to dig a little deeper.

New development eating up farmland

It’d be easy to miss Jason Roland’s farm if you weren’t looking for it.

Sandwiched between a conventional subdivision built up in the late 2010s and White Knoll High School, a few small plots of tilled dirt on his 16 acres of land yield kale, cabbage and sweet potatoes.

Each Thursday, Roland typically transported boxes of his produce to Hunter-Gatherer at the Hangar, a brewery in Columbia’s Rosewood neighborhood, where loyal customers who sign up to pick up produce ahead of time met him for their individual bags. He’s not sending his harvested crops to large grocery stores.

Development has been creeping in Roland’s direction for years, since before he began selling his produce directly to customers, a system known as community-supported agriculture (CSA), in early 2020. The 30-year-old grew up in the 70s-built home on the property with his mom. He now lives there with his wife, Ami. Their farm in the Red Bank area is less than two miles from an upcoming $65 million mixed-use development set to bring a Lowes Grocery store and a Planet Fitness, among other large retailers.

“I can remember being, I don’t know, maybe 12 years old, there were maybe a couple hundred cars that would pass [through] here every day,” Roland said. Now that number sits around 8,500 cars each day, according to state traffic data.

Roland’s time working the crops barefoot while blasting his favorite songs is coming to an end. He sold his family’s land amid the boom in development in Lexington to move to Ellerbe, N.C. where he plans to expand his farming operation. His decision to sell as new homes and commercial development spill over from larger metropolitan areas into rural communities, which Roland said contributed to his decision to leave, has become a more common story for farming families around the state.

When farmers die and children inherit their land, families are often left with a choice: pocket a decent chunk of change from developers for the sale of the land or labor away on the farm, an often grueling job that comes with financial risk.

“You’re gambling every single day that you’re a farmer, you can have something like what happened with the hurricane,” Paul Grant, who owns Freshly Grown Farms in Columbia, said of the September 2024 storm Helene. “I could’ve come in the morning after the hurricane and all of my greenhouses are completely blown away.”

The amount of farmland across the state has declined steadily over the last century, with the most drastic dip happening between the 1950s and mid-1980s. South Carolina was more than 60% farmland in 1935, data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture shows. In 2022, less than 25% of the state was farmland.

And as fewer farmers follow in the footsteps of generations ahead of them, the average age of a farmer in South Carolina, and nationally, is on the rise. Forty years ago, the average farmer in South Carolina was around 52. In 2022, the last time the agriculture census was taken, that number had risen to almost 59.

It’s a trend occurring across the country – the average age of a farmer in the United States has risen by almost eight years over the last four decades and sits around South Carolina’s average number.

As South Carolina farmland decreases, it’s become more concentrated on larger farms. From the 1940s to the ‘80s, the number of farms dropped off while the average acreage increased exponentially, as larger farmers held on to market share and younger farmers struggled to break through.

‘Huge barrier’ for young farmers

New farmers face two main types of challenges: financial and strategic.

The biggest barrier is capital, young farmers and industry experts said. Purchasing land and obtaining equipment ranging from tractors to cattle can make or break whether a budding farmer successfully enters the industry or leaves entirely.

For farmers who don’t have cash in hand, they typically have to turn to loans because the federal Department of Agriculture doesn’t dole out grants for buying land.

“If we had to go buy this land, there’s no way we could afford it,” said Dobbins, the Townville cattle farmer. He rents his 100 acres from his grandmother, who’s had the land for the better part of a century.

Roland inherited the farmland, which had been in his family for six generations, from his mother. Paul Grant, with Freshly Grown Farms in Columbia, purchased his land following the 2008 housing crash and was given his first greenhouse during the foreclosure of a farm in Asheville.

But unless inherited, obtaining the land to start a farm is a hurdle few new farmers can get over. And even if they do, many can’t afford necessary equipment or capital like tractors, planting supplies and animals.

The other barrier revolves around strategy – knowing how to do business and filling a niche that other farmers aren’t.

Farmers know how to farm, how to reap and sow crops and tend the land. But they often don’t know how to run the business side of things, how to market themselves and keep their books in order.

“They’re out there, sun up to sun down. The last thing they want to do when they get in is sit down and go over their books. That’s a huge barrier, just having that business acumen,” said Kyle Player, the executive director of the S.C. Department of Agriculture’s Agribusiness Center for Research and Entrepreneurship (ACRE).

For its part, the state’s agriculture department has made a concerted effort to recruit new, younger farmers and to encourage different types of agribusiness that aren’t just farming.

Over the last two decades, the agriculture department has put on a week-long summer program, called the South Carolina Commissioner’s School for Agriculture, for high school students to encourage them to get involved in the farming industry.

“They’re thinking of people on a tractor and getting down in the dirt and things like that,” Player said. “It’s beyond the traditional, what you think of, hands in the dirt.”

For example, people entering the agribusiness industry might put more of an emphasis on things like agritourism or creating artisan products like jams and honey.

Leading ACRE, Player helps with an agribusiness development program that takes a group of about a dozen farmers through courses that help them come up with a business plan and learn about resources. The farmers then pitch their plan to a panel of judges for a chance to get one of five $5,000 grants from the department.

New ways forward

As land remains expensive and often unattainable for farmers looking to break into the industry, Player said she’s seen an increase in urban farming. Instead of traditional row crop farming, with long aisles of produce stretching for hundreds of acres, new farmers have turned to things like large shipping containers, greenhouses and hydroponic growing.

In many ways, newer farmers have also changed how they do business. While larger, multi-generational farms might send produce to grocery stores or close-by food hubs for distribution, smaller, urban farmers turn to local restaurants, farmers markets or create CSAs with others, as Roland in Red Bank did.

“This is not what you think of when you think of farmers in South Carolina,” the Lexington County farmer said. “It’s [not] ‘Alright, I’m growing 180 acres of soybeans and I need this big giant tractor and all the chemicals and all the things.’ You know, I’m all about all-organic and just staying as natural as possible.”

The shift in how new farmers do business is one that could lead to positive change in the agriculture industry, said Najmah Thomas. Thomas has worked with the S.C. Black Farmers Coalition and with the agriculture department’s ACRE program to get young students of color involved in agriculture.

Thomas said she’s seen a shift in the last few years in the industry, but believes it’s still got a ways to go.

“If we are able to keep our foot on the gas a little bit, continue to support the kinds of programs that’ve made it possible to increase access and then to support the next generation of either farmers or agribusiness owners … I see the future of farming as very healthy, very equitable,” Thomas said.

’Nobody wants to talk about death’

It took a pointed conversation with a feed salesman for Loyd “LD” Davis, Jr.’s father to make peace with the fact his son chose to stay in the dairy industry.

The senior Davis, a second generation farmer, had repeatedly lectured his son for throwing away his college education to return to the farm. But when he made a comment to a friend and feed salesman, he got pushback.

“Fred said, ‘Loyd, what the hell are you talking about … that education, he’s going to carry with him from now on,’” Davis, 71, said.

But, in some ways, as Davis got older, he understood where his dad was coming from. He required his daughter, Iris Barham, to move away from the farm for a while, get an education and try out something different. He wanted to know she was sure about her decision to stay.

Barham returned to Starr, a town of less than 200 people just a few miles from the Georgia border, amid the COVID-19 pandemic. She’s now in business with her dad and brother, Loyd Davis, III at Milky Way Farm.

But even when younger generations like Barham and her brother choose to stay in the business, emotions around retirement and contingency plans can run high and cause families to put off those conversations.

“Nobody wants to talk about death,” Barham said. “There’s a lot of emotions caught up in that. For my dad, who’s 71 years old, you have 50 years of life’s work. It’s not easy for some people to talk about transitioning.”

For the time being, the family behind Milky Way Farm has been buying additional land and adding new technology to make the work sustainable for future generations. Barham has two children and so does her brother. The hope is that at least one of them will want to stay in the industry, but not without seeing the world a bit first.

“We want them to come back and we’re making investments for it to be here for them, but we don’t want them back so far that they don’t learn what we learned by going off,” Barham said.

©2025 The State. Visit at thestate.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments