Freed from scandal, Wells Fargo Sets Its Sights on Growth

Published in Business News

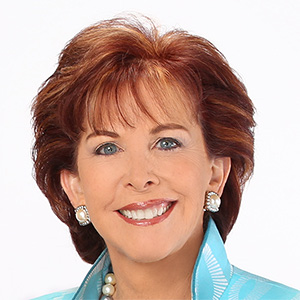

Charlie Scharf can finally play offense.

After more than a half-decade cleaning up Wells Fargo & Co.’s scandals, the chief executive officer has cleared away the firm’s biggest impediment to growth: the Federal Reserve’s seven-year-old cap on assets. That means the $1.95 trillion lender can once again seek to narrow the gap with larger rivals JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Bank of America Corp. — including in Wall Street business lines.

The unshackling of Wells Fargo sets up stiffer competition among the biggest U.S. banks — and a new chapter for Scharf, who has sought to keep a low profile since taking over in late 2019. That will change, according to people familiar with his thinking. As one of them put it, the job is just starting to be fun, and Scharf, 60, plans to stick around for that.

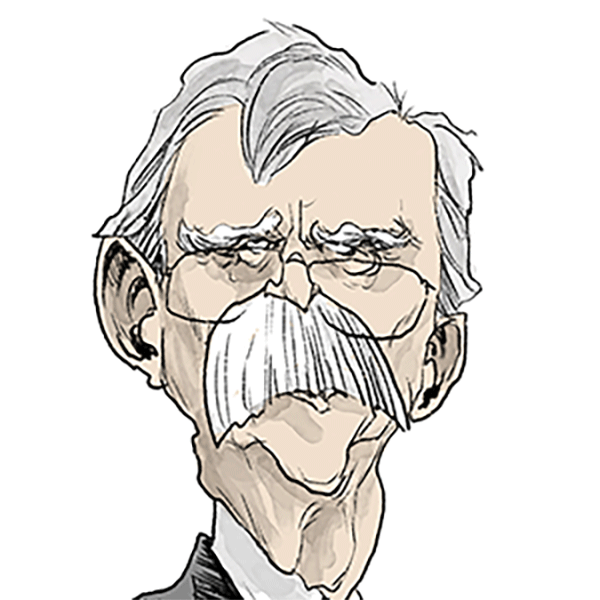

“Charlie has worked extremely hard over the years to resolve heritage issues at the bank and to get to this place today, and he and his team deserve a lot of credit,” said Jamie Dimon, the longtime JPMorgan Chase & Co. CEO who hired Scharf out of college and turned him into a protégé. “This is not only good for Wells Fargo but for the industry overall.”

After months of Wells Fargo executives awaiting a verdict, the Fed’s announcement Tuesday was so abrupt that many of the bank’s senior leaders were scattered. Some were attending an intern orientation in Orlando. Its chairman was celebrating his 73rd birthday.

Until that moment, Scharf had mostly been a fix-it guy at Wells Fargo — the fourth leader to attempt to wrestle its problems into submission. Yet in the decades before his arrival, he focused on growing businesses.

He helped Dimon build the modern JPMorgan, then jumped to Visa Inc., where he more than doubled its stock price in four years. During that time, he oversaw the roughly $20 billion purchase of Visa Europe and reshaped the payments firm to compete with emerging competitors including PayPal Holdings Inc. He was just settling into his next CEO gig at Bank of New York Mellon Corp. when Wells Fargo announced in 2019 that it had lured him away.

With the asset cap gone, shareholders will be eager to hear much more about strategy. The outlines of Scharf’s aspirations are little secret.

His team has been laying the groundwork and making targeted hires for years to ramp up trading operations that were limited by the cap. They have also been adding investment bankers in a bid to win more underwriting and advisory business. Scharf also marked credit cards and wealth management as key growth areas in his early years at the bank, and that list will likely expand now that the cap is gone.

“I honestly believe, with the exception of the mortgage business, all have the opportunity to grow in terms of returns and in terms of rate of growth,” Scharf said Wednesday in a CNBC interview. “And we have a little bit of a head start in the card business because we identified that as something strategically important early.”

Shares of the company were the best performers Wednesday in the S&P 500 Financials Index, jumping 2% and bringing this year’s gain to 9.2%.

Wide gap

The gap between Wells Fargo and other Wall Street banks is still wide. The firm’s trading revenue and investment-banking fees last year were about the same as what JPMorgan earned from those businesses in the fourth quarter alone.

This look at the clean-up and strategy is based on accounts from people with direct knowledge of the matter, who asked not to be identified discussing behind-the-scenes events. A spokesperson for Wells Fargo declined to comment beyond a statement Tuesday calling the Fed’s decision a “pivotal milestone” for the bank.

The Fed imposed the asset cap after years of mounting frustration with the firm’s reaction to scandals, including the revelation that it had opened millions of accounts without customers’ permission. The unprecedented measure limited Wells Fargo’s balance sheet to its size at the end of 2017 until the lender finished shoring up risk management and board effectiveness to the Fed’s satisfaction.

That required a ground-up rebuild of those operations that neither side expected to take so long. The punishment proved so tenacious and costly that it’s now the most-feared sanction in bank regulation. By one measure it caused Wells Fargo to miss out on almost $39 billion of profits.

When Scharf accepted the job more than a year after the cap began, he didn’t know how much work remained. After all, any progress — or lack thereof — on regulatory sanctions fell in the bucket of “confidential supervisory information” that firms are strictly forbidden from revealing. His impression when he was recruited as CEO was that the firm was probably less than a year away from getting the cap lifted, according to people with knowledge of the situation.

In a conference call just after his appointment, he told listeners that he appreciated “all the work that has already taken place to begin the transformation of Wells Fargo.”

Low point

Shortly thereafter, he learned that the bank’s proposed overhauls hadn’t even been accepted by the Fed, one of the first hurdles toward lifting the cap. As Scharf assembled his team and embarked on deep reviews of business lines, they discovered the lack of progress extended beyond just the Fed’s order.

Authorities had laid out more than a dozen public orders and hundreds of “matters requiring attention” — regulatory parlance for a nonpublic warning to fix something or face further escalation. Failing to address such issues quickly enough can turn into public orders and fines. For each one, Scharf held meetings on progress and planning.

The firm’s predicament worsened before improving. After the pandemic set in, Wells Fargo reported a quarterly loss for the first time in more than a decade and slashed its dividend. In September 2021, as Scharf neared his two-year anniversary as CEO, the bank was hit with a fresh sanction over a lack of progress addressing long-standing problems in the mortgage business.

As Wells Fargo fell further behind its own estimates for reforms, some executives privately began wondering if they were facing an impossible task and whether regulators would ever let them out of consent orders. Now, they look back on that time as the lowest point in the turnaround.

Shrinking workforce

Around late 2022, they started seeing signs of progress. Optimism mounted through 2023, and by a board meeting in New York that December, executives were confident they would meet their deadlines to submit the rest of their work to regulators — and that they were getting it right.

One of the final steps for the asset cap was a third-party review of their work, which alone cost about $100 million. They submitted that last year.

While untangling the regulatory mess, Scharf and his team worked on a second track: reshaping the firm.

Improving earnings with the cap in place meant shrinking or shutting businesses that Scharf’s reviews deemed less desirable while freeing up room on the balance sheet for others. He dialed back the firm’s massive home-lending empire, once the largest in U.S. finance. He sold the bank’s asset manager, corporate-trust unit, student-loan book, rail financing portfolio and most of its commercial mortgage servicing business.

He also did away with the folksiness that his predecessors had long embraced. The stagecoach logo was left by the wayside. He stopped calling employees “team members” and then slashed their ranks by nearly 60,000 and counting.

He split the corporate and investment bank into its own unit and marked it for growth, repeatedly saying that the fourth-largest U.S. bank shouldn’t be “afraid” to talk about its Wall Street presence. That contrasted with predecessors who had long said the main purpose of the firm’s securities operations was to respond to the needs of companies that did business with other parts of the bank.

Dimon’s advice

One person who long predicted that Wells Fargo would someday become more formidable on Wall Street is Dimon. The JPMorgan CEO repeatedly warned his own shareholders about Wells Fargo’s potential — until its scandals began erupting.

Privately, he later predicted that Wells Fargo would rise again.

On the day Scharf’s appointment as CEO was announced, his vice chair at BNY, Bill Daley, was pondering his own future on a walk down Greenwich Street in lower Manhattan when he got a call from a blocked number. It was Dimon, his old boss and longtime friend.

Don’t do anything stupid like go back to Chicago, Dimon told the Windy City native. Dimon added: Wells Fargo is a great institution and Charlie will fix it — this is what he does. Daley ended up joining Scharf at Wells Fargo later that year.

(With assistance from Daniel Taub.)

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments