Unprecedented 'jobless boom' tests limits of US economic expansion

Published in Business News

The U.S. economy is creating plenty of wealth. It’s just not creating many jobs.

Forecasters expect Friday’s report on gross domestic product to show the economy expanded 2.7% in 2025, a solid pace by any standard for a developed country. But employment barely grew, and the combination is drawing comparisons to the infamous “jobless recovery” of the early 2000s that followed the tech bubble and collapse.

There’s one major difference between then and now that makes the current divergence all the more unusual: The 2000s episode kicked off with a recession. This time, the “jobless boom” is happening without one. That marks a first in the postwar era.

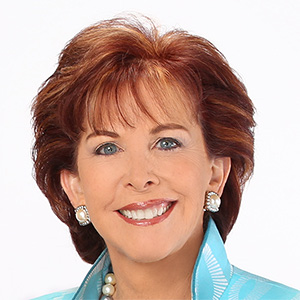

“We have never seen anything later in an expansion like what we are seeing today, and that’s what makes it so unusual and hard to judge about where we are going,” said Diane Swonk, the chief economist at KPMG. “At the end of the day we are sitting on a one-legged stool, which is not the most stable place to be.”

President Donald Trump will likely tout strong GDP numbers during his first year back in the White House at his annual State of the Union address to Congress on Feb. 24. The economy was supported in 2025 by resilience in consumer spending alongside rising stock prices and a pickup in business investment driven by the artificial intelligence boom, despite drastic changes in trade and immigration policies that added uncertainty to the mix. Data out Wednesday confirmed business investment ended 2025 on a high note, and manufacturing output rose in January by the most in nearly a year.

Trump and his allies are urging the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates, arguing the U.S. central bank should take a page from the playbook of its former chairman, Alan Greenspan — who in the 1990s famously predicted rising productivity could be setting the stage for a period of faster growth without higher inflation.

But the economy today is starting to look less like the one in the 1990s than what came after, which then-Fed Governor Ben Bernanke identified in a 2003 speech on the “jobless recovery.” Much like then, nationwide headcount flatlined in 2025 amid a broad-based pullback in hiring across industries, despite the strength of GDP.

A big focus of Bernanke’s speech was the loss of manufacturing jobs, which had already been in a decades-long decline and were at the time being dealt another major blow from China’s rise as factory floor to the world.

Between 2001 and 2005, though, the segment of the workforce employed in office and administrative support roles experienced job losses of a similar scale as the tech boom left a trail in its wake, shedding 1.3 million positions alongside the 1.7 million decline in production roles.

Michael Pearce, the chief U.S. economist at Oxford Economics, drew an explicit parallel to the aughts in a Feb. 11 report on the outlook: “Conditions that led to the jobless recovery in the early 2000s are aligning, such as overhiring, robust productivity growth, technological advancements, and increased policy uncertainty,” he said. “This leaves the economy vulnerable to shocks, because the labor market is the main firewall against a recession.”

In the 2000s episode, the pain of unemployment was spread across the spectrum of educational attainment. This time around, college-educated Americans are bearing the brunt of the slowdown, faced with rising unemployment even as jobless rates among their non-college counterparts have declined.

Office jobs

Many of them are on the front lines of the battle to expand AI in white-collar workplaces across the country, the success of which may be key to keeping the current productivity boom — already being reflected in official statistics as the GDP-jobs gap widens — going in the years ahead.

“AI could bring productivity gains over the next few years and it could be quite significant, which of course means that we may see less job growth than you would ordinarily,” said Stephen Stanley, the chief U.S. economist at Santander Capital Markets. “But I would be surprised if that is making a huge impact just yet.”

Crystal Mason, 45, was notified in mid-December that she was being laid off from her job as a contractor at a call center. In that role, she helped military service members schedule mental health assessments and handled after-hours calls from suicidal individuals.

Now the Holly Ridge, North Carolina resident is looking for similar work, and she says her current job search has been distinctly more challenging than the last one two years ago, when she consistently received offers following job interviews.

Mason, who has an associate degree, says she wonders how AI will impact availability of such positions going forward. She also suspects she’s up against a flood of other laid-off job seekers who are applying for anything they can find. Of the applications she’s submitted this time around, two have resulted in interviews, 42 have been rejected and 64 haven’t even responded.

“I’ve noticed other companies I’ve worked at, or where friends work, are already using AI and reducing roles for people who do what I do,” she said. “The sad part is, from my years of experience in customer service and health care, I’ve learned that almost everyone I interact with prefers talking to a real, empathetic, professional person.”

Americans working in office and administrative support positions like Mason’s saw the biggest increase in unemployment in 2025. It was the clearest part of a broader pattern of reallocation within the pool of unemployed workers last year toward white-collar occupations and away from blue-collar roles.

Investors, meanwhile, are reaping the benefits of such cost-cutting programs across Corporate America. U.S. stock indexes are near record highs, and corporate profit margins remain near the widest levels of the post-World War II era.

How much work has actually been replaced by AI to date is a matter of some debate among economists. Fed Chair Jerome Powell argued in a recent press conference that the current wave of rising productivity started five or six years ago — in other words, before the mass rollout of large language models.

Some of his colleagues have instead suggested process improvements and reorganization of business models originally spurred by the pandemic are now starting to pay off. In December, the last time Fed officials issued economic projections, they boosted their outlook for GDP growth in 2026 while leaving their estimates for the unemployment rate unchanged.

‘Unlike anything’

Danielle Williams, 40, took a job last year as a senior lead recruiter for a midsize firm focused on civil and commercial electrical projects, then was laid off in November after five months in the role. Since then, the Miami resident has only been able to find a six-month contract position at a similar company.

“I’m very familiar with the labor market and market trends because I have been in the recruiting industry for the past 12 years,” Williams said. “This market has been really crazy, unlike anything I’ve ever seen.”

The latest monthly jobs report published on Feb. 11 by the Bureau of Labor Statistics showed job growth was weaker in 2025 than initially reported, but it also showed hiring picked up in January. Private-sector employers added 172,000 workers to payrolls, a figure representing almost half of last year’s entire increase.

January’s gains, however, were overwhelmingly concentrated in health care and social assistance, much as in 2025. Construction jobs were also a major driver of the jump, whereas employment sectors predominantly staffed by white-collar workers mostly lagged behind.

By and large, the outlook is for continued steady economic growth and only a slight improvement in the labor market. But some economists, like Mickey Levy, aren’t optimistic that rising productivity can continue to carry the U.S. economy if it’s not passed on in the form of higher wages. Right now, that’s not happening — wage growth has been decelerating as workers have lost bargaining power in negotiations with their employers.

“It’s too early to compare this episode of strong GDP, weak employment to earlier episodes, where the relationship was sustained for much longer,” said Levy, a visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution. “Economic growth will be slowing significantly to reflect the stagnant labor markets.”

©2026 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments