Christian Zionism hasn’t always been a conservative evangelical creed – churches’ views of Israel have evolved over decades

Published in News & Features

During confirmation hearings, Mike Huckabee, President Donald Trump’s nominee as ambassador to Israel, told senators that he would “respect and represent the President,” not his own views. But the Baptist minister’s views on the Middle East – and their religious roots – came through.

“The spiritual connections between your church, mine, many churches in America, Jewish congregations, to the state of Israel is because we ultimately are people of the book,” he said on March 25, 2025, in response to a question from a senator. “We believe the Bible, and therefore that connection is not geopolitical. It is also spiritual.”

Huckabee is one of the GOP’s most prominent “Christian Zionists” – a phrase often associated with conservative evangelicals’ support for Israel.

But Christian Zionism is much older than the 1980s alliance between the Republican Party and the religious right. American Christian attitudes toward the idea of a Jewish state have been evolving and changing dramatically since long before Israel’s creation.

Zionism’s modern form emerged in the late 19th century. Its declared aim was to create a Jewish homeland in the region of Palestine, then under control of the Ottoman Empire. This was the land from which Jews were exiled in antiquity.

The “founding father” of the modern movement was Theodore Herzl, an Austro-Hungarian Jewish intellectual and activist who convened the first Zionist Congress in Switzerland in 1897. While most of the 200 attendees were Jews from various parts of the world, there were also prominent Protestant Christian leaders in attendance: church leaders and philanthropists who supported “the restoration of the Jews to their land.” Herzl dubbed these allies “Christian Zionists.”

Catholic leaders, however, were not among the supporters of a Jewish state. The prospect of a Jewish state in the Christian Holy Land challenged the church’s view of Judaism as a religion whose people were condemned to permanent exile as punishment for rejecting Christ.

Eventually, in the wake of the Holocaust and the establishment of Israel, attitudes shifted. In 1965, reforms at the Vatican II council signaled a radical change for the better in Catholic-Jewish relations.

But it would be three decades until that change was reflected in the Vatican’s diplomatic recognition of the Jewish state.

In contrast, Protestants were more open to Jews’ aspiration to return. In 1917, the British foreign secretary published the Balfour Declaration, announcing government support for “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.” With the British victory over the Ottoman Empire, the area soon fell under British control in the form of the League of Nations’ Mandate for Palestine.

In the U.S., the idea elicited enthusiasm among conservative Christians who hoped that the Jews’ return to Israel would help hasten the end times, when they believed Christ would return. Within a few years, Congress endorsed the Balfour Declaration.

Pastor W. Fuller Gooch summed up the evangelical reaction to the Balfour Declaration: “Palestine is for the Jews. The most striking ‘Sign of the Times’ is the proposal to give Palestine to the Jews once more. They have long desired the land, though as yet unrepentant of the terrible crime which led to their expulsion.” This “terrible crime” refers to Jews’ rejection of Jesus – one of multiple anti-Jewish tropes in the sermon.

Two decades later, prominent American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr declared himself a supporter of political Zionism. Unlike evangelicals, Niebuhr’s support for a Jewish state was based on pragmatic grounds: Considering the dangerous situation in 1930s Europe, he argued, Jews needed a state in order to be safe.

In the early 1940s, Niebuhr wrote a series of articles titled “Jews After the War” for The Nation magazine. His biographer Richard W. Fox called these articles “an eloquent statement of the Zionist case: The Jews had rights not just as individuals, but as a people, and they deserved not just a homeland, but a homeland in Palestine.”

Thus, in the 1930s and ‘40s, two different types of American Christian Zionism emerged. Some liberal Protestants, while giving qualified support to Zionism, expressed concern for the fate of the Palestinian Arabs. Conservative evangelicals, on the other hand, tended to be more hostile to Arab political aspirations.

In 1947, on the eve of the United Nations’ vote on the partition of Palestine, Niebuhr and six other prominent American intellectuals wrote a long letter to The New York Times, arguing that a Jewish state in the Middle East would serve American interests. “Politically, we would like to see the lands of the Middle East practice democracy as we do here,” they wrote. “Thus far there is only one vanguard of progress and modernization in the Middle East, and that is Jewish Palestine.”

In 1948, the U.S. government, at President Harry Truman’s direction, granted the newly declared state of Israel diplomatic recognition, over the objections of State Department officials.

There were, of course, prominent Americans who objected to recognizing Israel, or to embracing it so strongly. Among them was journalist Dorothy Thompson, who had turned against the Zionist cause after a Jewish militant group bombed Jerusalem’s King David Hotel in 1946. These opponents made the case for supporting emerging Arab nationalism and Palestinian autonomy and asserted that recognizing Israel would deepen America’s entanglement in the unfolding Middle Eastern conflicts.

But by the late 1950s and ‘60s, American criticism of Israel was increasingly muted. Liberal Christians, in particular, viewed it as a beleaguered democratic state and ally.

Conservative Christian Zionists, meanwhile, continued to often view “love of Israel” through a biblical lens.

In the late '60s, the American journal Christianity Today published an article by editor Nelson Bell, father-in-law of famous evangelist Billy Graham. Jewish control of Jerusalem inspires “renewed faith in the accuracy and validity of the Bible,” Bell wrote.

Fifteen years later, televangelist Jerry Falwell told an interviewer that Jewish people have both a theological and historical “right to the land.” He added, “I am personally a Zionist, having gained that perspective from my belief in Old Testament scriptures.”

These Christians, like some Jewish religious Zionists, saw “the hand of God” in Israel’s conquest of East Jerusalem during the Six-Day War of 1967. They considered any territorial compromise with Arab states and the Palestinians to be an act against God.

During the 1980s, as the Republican Party forged alliances with the emerging religious right, Israel would become a core cause for the GOP. Some liberal Jews who supported Israel grew alarmed by these ties and by the rightward shift in Israeli policies toward the Palestinians.

Yet this brand of Christian Zionism is clearly the forerunner to today’s – and holds sway in Washington. Today, 83% of Republicans view Israel favorably, compared with 33% of Democrats. Republicans in Congress are pushing to use the biblical terms “Judea and Samaria” instead of “the West Bank.” Evangelical Christian Zionists continue to call for support of the Israeli right and of settlers in the occupied territories.

And in Huckabee, they see a potential ambassador who shares their views.

In 2009, when Huckabee was considering a presidential campaign, he visited Israel and met with settler leaders. On hearing of Huckabee’s presidential aspirations, a rabbi said, “We hope that under Mike Huckabee’s presidency, he will be like Cyrus and push us to rebuild the Temple and bring the final redemption.” The rabbi was referring to the biblical story of Cyrus, King of Persia, and his proclamation that the exiled Jews be allowed to return to Zion.

Seven decades after the state of Israel’s founding, evangelical Christian Zionism’s influence is greater than ever. This turn to the political right is very far from the mid-20th century Zionism of Truman, Niebuhr and the Democratic Party.

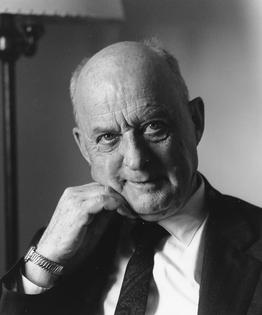

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Shalom Goldman, Middlebury

Read more:

Palestinians have long resisted resettlement – Trump’s plan to ‘clean out’ Gaza won’t change that

Jewish critics of Zionism have clashed with American Jewish leaders for decades

When is criticism of Israel antisemitic? A scholar of modern Jewish history explains

Shalom Goldman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments