New details about police activity after lawmaker shootings raise questions about response

Published in News & Features

MINNEAPOLIS — From the first 911 call, moments after Minnesota state Sen. John Hoffman and his wife, Yvette, were shot at their home in the early morning of June 14, police knew a masked gunman was impersonating an officer, had targeted a politician and was on the move.

Yet it would take 10 hours for law enforcement to systematically alert lawmakers to the exact nature of the danger they faced. Communication across a patchwork of agencies was also spotty, leaving some officials unaware of the threat for hours and raising questions about whether the suspect, Vance Boelter, could have been caught earlier.

In at least one instance, police didn’t follow their own procedures when they responded to attacks on the homes of lawmakers. The shootings killed Rep. Melissa Hortman and her husband, Mark, and wounded the Hoffmans.

A Minnesota Star Tribune investigation has found new details about the law enforcement response to the shootings, including:

—The initial 911 call, made at 2:05 a.m. by the Hoffmans’ daughter, Hope, included the fact that the suspect was disguised as a police officer and wearing a mask.

—In a deviation from department policy, Brooklyn Park police waited more than an hour to enter the home of Melissa Hortman after watching Mark Hortman get shot in the doorway.

—New Hope police didn’t immediately communicate an officer’s interaction with Boelter, which occurred after the Hoffmans were shot but before the Hortmans were killed.

—Some police officers and legislators weren’t made fully aware of the threat for several hours.

“There wasn’t a playbook for this, and I think that was clear,” said DFL Sen. Erin Maye Quade.

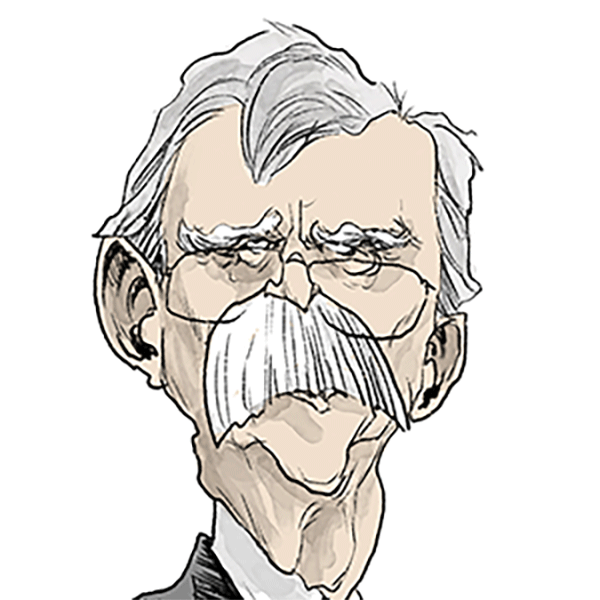

Boelter is now facing state and federal murder charges, state attempted murder charges, and federal charges of stalking and use of a firearm.

State Public Safety Commissioner Bob Jacobson said that “law enforcement did an admirable job of trying to respond and make sure they were doing their very best in this case.”

Still, Jacobson said public safety leaders ordered a review of their conduct that morning, and Minnesota’s Office of the Legislative Auditor said it would consider launching its own investigation into how communication was shared.

“We have received several requests to do an inquiry or a review related to the communication around the rapid response,” Legislative Auditor Judy Randall said Thursday.

Quick action, missed chances

The first interaction between law enforcement and Boelter took place near the home of Sen. Ann Rest at 2:36 a.m. when a New Hope police officer “self-dispatched” to perform a spot check on Rest’s home. The officer, a 12-year veteran, encountered Boelter sitting in his makeshift police vehicle.

The officer believed Boelter was a police officer who was checking on Rest and asked Boelter to roll down his window. He was a “bald, white male, staring straight ahead,” according to court records. Boelter didn’t respond to the New Hope officer, who left to check on Rest.

When the officer returned, Boelter was gone.

Several sources with knowledge of the investigation said the officer’s interaction with Boelter was not reported to other law enforcement agencies in real time. Whether that’s because the officer didn’t report it or because police radio traffic was so heavy that the transmission didn’t go through is currently unknown.

It also isn’t clear what the New Hope officer knew at that time and why she was on her way to Rest’s home.

The New Hope Police Department has declined several requests to share more information about the interaction. They provided the Star Tribune with a police report on the incident that doesn’t make any mention of the encounter with Boelter.

The New Hope encounter occurred just minutes after police started reviewing the Ring camera footage from Hoffman’s house. The footage, which the Star Tribune reviewed, shows the suspect clearly dressed as an officer with what appeared to be a police vehicle flashing its lights in the driveway. The sound of Boelter allegedly shooting the Hoffmans isn’t captured, but as he climbs back into his SUV, someone inside the home says, “Call 911.”

A transcript of that 911 call was provided to the Star Tribune this week. It was heavily redacted but showed Hope Hoffman telling dispatchers her father was a state senator. A source who has heard the audio of the 911 call said that Hope describes the suspect as impersonating law enforcement and wearing a mask. Body camera footage reviewed by the Star Tribune shows a police officer outside the Hoffman residence watching the Ring camera footage at 2:25 a.m.

Inside law enforcement circles, Boelter’s interaction with the New Hope officer after the shooting of the Hoffmans was instantly critiqued.

A video shared with the Star Tribune that was allegedly passed among officers within days of the shootings includes a clip from the film “The Town” that shows a group of bank robbers dressed as nuns and wearing silicone masks when they pull up beside a Boston police officer. The men are holding guns and the officer stares at them for several seconds before letting them leave.

In the modified clip, the logo for the New Hope Police Department is superimposed on the cop car.

Mylan Masson, a retired Minneapolis police officer and former police trainer, said it’s not uncommon for cops to second-guess other officers, especially in high-profile situations, and cautioned against rushing to judgment before knowing all the facts.

Masson said that’s especially true in this unique situation. She noted it was dark, the car looked like an unmarked police vehicle and the driver was dressed as a cop. On top of that, the officer was going to check on Rest and went to complete that task.

“There’s so many unknowns,” Masson said.

After gunfire, police wait an hour to check on Hortman

About the same time officers at the Hoffman residence were reviewing the home security footage, some police departments began checking on state politicians.

But it took more than an hour for Brooklyn Park police to visit the Hortman home.

At 3:35 a.m., two Brooklyn Park police officers arrived at the Hortman residence. Those officers fired at Boelter as he entered the house after shooting Mark Hortman. Additional muzzle flashes from Boelter inside the home lit up the entryway.

Despite the gunfire, officers didn’t enter the house until 4:38 a.m., according to time stamps on the bodycam footage. Instead of entering the home immediately to check on Melissa Hortman, the officers waited for a drone to be deployed to see if Boelter was inside and if Melissa Hortman was still alive.

A source familiar with the drone footage said Hortman is shown immobile and curled up on the landing at the top of the stairs.

At 4:42 a.m., Melissa Hortman was taken out of the house and brought to an ambulance.

Brooklyn Park Police Chief Mark Bruley has said his officers believed they shot Boelter and he was “holed up” in the basement.

After shooting the Hortmans and the family dog, Gilbert, Boelter allegedly escaped out the back door, which was propped open. He then dumped his mask, wig and gun, and was on the run for 43 hours before being captured.

Bruley said in an interview with the Minnesota Reformer this month that his officers were using de-escalation tactics in the pursuit of Boelter.

A senior law enforcement official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity and has been in several active shooter situations, said this was not a situation that called for de-escalation but fit the description of an active shooter. That meant officers should have gone into the house to confront Boelter.

Brooklyn Park’s use-of-force policy says officers can use deadly force to prevent death or great bodily harm. It says de-escalation can only be used when delay will not “compromise the safety” of someone else, lead to another crime or result in the suspect’s escape.

The Brooklyn Park Police Department declined to answer specific questions about the timeline of activity at the Hortman home.

In a statement, the department said it’s focused on bringing Boelter to justice and has requested an after-action review of the shooting to “highlight both the commendable efforts and areas for improvement.”

Masson, the former police trainer, said if officers were trying to save Mark Hortman’s life while protecting each other from potential shots from Boelter, the decision to not immediately enter the house is understandable.

Asked if it seemed reasonable that it took an hour for anyone to physically check on whether Melissa Hortman was still alive, Masson said, “It seems like a long time. But I don’t know the circumstances of why.”

‘Every city was left to its own response’

After he escaped, the dire nature of Boelter’s plans was not immediately conveyed to politicians. Several were told to contact local law enforcement for protection only to learn their local law enforcement had no idea about the attack.

Sen. Jim Abeler was among the first legislators to hear of the shootings and get protection. The Republican said Anoka police knocked on his door at 3 a.m. to warn him a legislator had been shot, 35 minutes before officers arrived at the home of Melissa Hortman. Police returned a half-hour later, Abeler said, and told him, “If somebody comes back, call 911 to make sure it’s us.”

Other lawmakers didn’t get such prompt protection, Abeler said. He recalled a DFL senator asking him about her personal safety at 6:30 a.m.

“Every city was left to its own response,” Abeler said.

The first widespread dissemination of the information to law enforcement was sent out at 4:25 a.m. via teletype to agencies in the seven-county metro area. Jacobson said it’s the only system that exists to get the information to every dispatch center.

”We can maybe do better, but it’s a reminder those dispatch centers are open 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” he said.

A high-ranking leader in the Minnesota State Patrol was alerted to the shooting at the Hoffmans by an officer at the scene at 2:37 a.m., according to a source with knowledge of the investigation. The patrol contacted the House and Senate sergeants-at-arms about the shootings before 4 a.m., according to a spokeswoman. It’s unclear how much information the sergeants received or shared with lawmakers. They did not respond to questions from the Star Tribune.

Gov. Tim Walz’s chief of staff, Chris Schmitter, reached out to legislative leaders just after 4:30 a.m., warning that violent incidents had taken place at lawmakers’ homes.

About 5 a.m., Jacobson told House and Senate leaders to communicate with their caucuses about the violence as soon as possible, and that Bureau of Criminal Apprehension investigators were being sent to the Hoffman home.

An hour and a half later, Jacobson shared a message for legislative leaders to send to their members, warning of a “dangerous individual” who’s made threats against state legislators and other prominent figures. He urged lawmakers to contact their local law enforcement. He did not mention the suspected gunman impersonated a police officer and carried a list of targets.

Jacobson said the Department of Public Safety received the list of names from Brooklyn Park police “no later than 6:30 in the morning,” but it was a rapidly developing situation.

“It was just a very early, quick view of all those journals you’ve heard about,” Jacobson said. “The so-called list, or the names. That list continued to be edited and updated throughout the day.”

Walz and public safety leaders held the first news conference about the lawmaker shootings around 9:45 a.m., discussing what happened and sharing that the alleged assailant impersonated a cop and carried a list of targets.

The Department of Public Safety worked with federal authorities to share the initial list with relevant local law enforcement. But the DPS didn’t share the list with the House and Senate caucuses until 11:59 a.m., after Boelter had been on the run for several hours.

Maye Quade, the state senator from Apple Valley, said her local police department didn’t learn she was on the target list until about 9 a.m. Apple Valley police reached out to her quickly, but by that time, Maye Quade said she and her wife had already fled their home.

“It’s hard for me knowing that I was on a terrorist’s hit list, and he was successful in shooting one of my colleagues and his wife and murdering another colleague and her husband, and that information wasn’t shared with my local police department for hours,” she said.

“There’s nothing else my police department could have done because they didn’t know,” Maye Quade added.

Jacobson said his department is close to finalizing an agreement for an independent after-action review to show “what went well in a horrible situation and here’s what we can improve on.”

He added that he’s already hearing from law enforcement agencies across the state that are starting to build their own databases of local elected officials.

Col. Christina Bogojevic, chief of the State Patrol, said that going forward a system for alerting lawmakers of threats outside of the Capitol would be helpful.

The State Patrol has an emergency response system to alert lawmakers about threats on the Capitol campus, but it’s specific to that area, participation in the system is voluntary and the Legislature isn’t in session. That system wasn’t used the morning of June 14.

The communication gap left some legislators unaware they were possible targets. They didn’t know to be cautious if someone looking like a cop knocked on their door.

“When you hide information like the shooter is impersonating a police officer, and then no one tells you that,” said Sen. Heather Gustafson, DFL-Vadnais Heights. “I would have answered my door to Vance Boelter, and five out of my six family members were here.”

“I don’t know how to feel about that,” Gustafson added. “Who was supposed to tell me not to answer my door, and why didn’t they?”

———

(Allison Kite of the Minnesota Star Tribune contributed to this story.)

———

©2025 The Minnesota Star Tribune. Visit startribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC

Comments