Broadview residents are scared as ICE facility becomes a battleground for Trump immigration blitz

Published in News & Features

CHICAGO — From the open window in her dining room, Dana Caruso watched the bedlam unfold late last week off of 25th Avenue in Broadview. The road to an Immigration and Customs Enforcement facility is just across the street and the sight of unmarked ICE vans and protesters had already become commonplace, when early last Friday she heard what sounded like artillery fire and saw people running.

The smell of gas wafted through her window, an odor she finds difficult to describe but even harder to forget. She watched while men in what appeared to be military fatigues, dressed for battle, gave chase through the street and into her backyard. She could still see it all days later — and smell it, and hear it — while she sat at the window and recounted a morning that left her family traumatized.

Caruso relived the kind of scene that prompted Katrina Thompson, the mayor of Broadview, to publicly rebuke ICE and the Department of Homeland Security. Her village, a town of less than 8,000 people 13 miles west of Chicago, has become the unwitting epicenter of President Donald Trump’s crusade against illegal immigration, a campaign that has some locals hiding in fear and others loathing the smell of tear gas in the morning.

Since the Department of Homeland Security launched the so-called Operation Midway Blitz in early September, Fridays have been marked by violent clashes between ICE agents and demonstrators during planned protests at the detention center. After federal authorities deployed tear gas on Sept. 26 for the second straight week, DHS asked the Department of Defense to deploy 100 military troops to the Chicago area to help “end the migrant invasion and these lawless riots.”

Thompson’s response to the request was swift and unwavering.

“They are making war on my community,” she said.

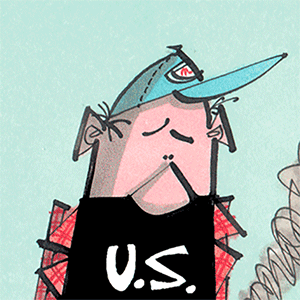

If there is a front line to that war, it’s along 25th Avenue, where protesters have gathered in recent weeks to confront ICE agents. It’s also where a few of the modest homes nearby have small manicured lawns with small American flags out front.

It was in one of those homes along 25th, where Caruso, 36, first heard what she thought to be some kind of an explosion. It was the sound of something from a war movie, and not anything she’d heard before along a typical suburban street that has become something of a broader metaphor, a physical manifestation of a divided country.

“I was telling my friend — I was like, ‘Girl, they are bombing these protesters.’ But, you know, it’s flash bangs,” Caruso said. “And then they were doing the tear gas. And then, even seeing those big rubber bullets.

“Those are huge. Imagine getting hit with one of those.”

“Have you seen one?” Caruso’s cousin, Christina Carr, asked, making the shape of a large round circle with her hands.

The cousins, who share the two-story brick home, found some of those rubber batons in their backyard, not far from the fence they say ICE agents broke as they stormed through the neighborhood.

Carr, 31, came outside to re-create the scene a few days later, but all she and Caruso could think about were the four children who live in the house — three of them Carr’s, one Caruso’s — who could’ve been outside playing. Who were outside, after things quieted, waiting to go to school.

“And they couldn’t even wait for the bus in front of the house,” Carr said, “because the tear gas was affecting them. I had to walk them two blocks that way for them to meet the bus driver.”

Before the events of recent weeks, when ICE agents began meeting protesters with tear gas and pepper spray, and before the deafening flash bangs became familiar, Carr said she did not know an ICE holding facility was so close by. The road that leads to it has been closed in recent days, guarded by agents, and Carr and Caruso have been afraid to take their kids to a nearby park.

If something were to happen, they said, they know they’d have to walk back through the melee. That sort of anxiety has gripped some people in Broadview, a village with elements of small-town America despite its proximity to Chicago. Along Roosevelt Road, which serves as the village’s Main Street, mom-and-pops line the sidewalks, which seemed quieter than usual this week.

“One day, I only had, like, 24 customers,” said Shaun Harrison, an assistant manager at the True Value Hardware off of Roosevelt.

He said that’s an unusually small number. And he wonders whether the ICE facility, located about a mile away, is the cause.

“I think that maybe it’s slowed down our business because people are scared,” he said.“But I don’t know … as far as I know, all that ruckus is staying over there.

“It’s not coming this way.”

The ripples of the ruckus, though, have extended throughout town. As Alphonso Richardson took his usual walk around his neighborhood one morning earlier this week, he said he feared for his friends who are Hispanic. He has lived in the neighborhood behind 25th Avenue for 13 years and hasn’t witnessed the ICE agents in the field yet.

“I don’t see it, myself,” he said.“But I hear about it — how they just walk up and grab somebody and take them away, and you don’t hear from them no more.”

About a mile away, Thompson, the mayor, prepared to face the public and walked out for a news conference, flanked by the Broadview police chief and fire chief, as well as a couple other local mayors. Lori Lightfoot, the former Chicago mayor, was there, too, and said she’d come to support Thompson and the people of her village.

Lightfoot described it as “profoundly disappointing” to see ICE agents roaming the streets of downtown Chicago and in boats patrolling the river. The scene in Broadview, though, has gone beyond that of mere public display. It has involved force, with ICE agents “acting in such a way like they are an armed militia accountable to no one,” Lightfoot said.

Thompson and local officials have called for ICE to remove a fence that blocks Beach Street, near the entrance to the detention center. That fence, adorned with profane messages written in black marker and directed against Homeland Security officials, separated an ICE agent and a woman who’d come in search of her mother around noon Tuesday. The woman did not want to give her name to a reporter, but asked the agent on the other side of the fence whether her mom was in the building, behind the boarded windows.

At that moment, a gate with barbed wire slid open and a black Chevy Express van backed out and slowly pulled away.

The agent, alone outside, came closer and asked, “Does your mom go by another name?”

The woman appeared perplexed. Moments later, the agent met someone else looking for a relative, the conversation playing out on opposite sides of the fence.

“Once he gets in here, they do the whole immigration piece of it,” the agent said, “and if he’s a United States citizen, then they’ll kick him. He’ll get his property back and he can make a phone call. … If he’s USC, we’ll let him go, for sure.

“We don’t hold on to U.S. citizens.”

Not far away, citizenship was of little consolation to a Broadview resident who identified herself as Mexican American and said she was born in Michigan. She lives close enough to the ICE facility that she, too, can smell the tear gas when it’s deployed. Now she’s too afraid to spend much time outside, too afraid to give her name while she washes her car in her driveway, one eye toward the street in case of the arrival of an unmarked van.

She pointed to her skin and noted her darker complexion. Despite having U.S. citizenship, she says she feels more at risk “because I am brown.”

“I’m scared,” she said, “because I don’t want to be detained three days in there before they find out I am American. Why would I have to go sit in there? Now I’m here and they’re taking everybody.”

They won’t look at her and assume she was born in the United States, she said.

“I’m Mexican American. But so what?,” she said. “They don’t see that. They see the color brown.”

Nowadays, her grandchildren beg her to stay inside. But sometimes they feel unsafe there too. Upon the most recent deployment of tear gas, the woman said, her family could feel it more than they could smell it .

“My grandbabies, they said, ‘Grandma, my skin’s burning,’” the woman recalled.

The woman said she turned off the air conditioning to try to keep the chemicals from coming through the vents.

Days later, she could not describe the smell of the gas. Just that “it burns” and that it made her chest hurt.

She couldn’t be sure, though, whether the pain was from the chemicals or the fear.

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments