Netanyahu enters campaign mode, claiming he saved Israel

Published in News & Features

TEL AVIV, Israel — Two years ago, after Hamas killed and kidnapped its way across southern Israel, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu seemed finished. “Mr. Security,” as he billed himself, would either resign in shame or be driven out by a devastated public.

Yet this week he promoted his candidacy in next year’s election by saying he’d saved the nation from oblivion with a slew of military successes against Iran and its proxy militias. Between those and a fractured opposition, it’s looking like the country’s longest-serving leader may hold onto his post for a while longer.

“He doesn’t need to win the next election, just not to lose it,” said Nadav Shtrauchler, a political adviser who’s worked closely with Netanyahu in the past, referring to the possibility of remaining in power without a majority. “He’s still there, astounding observers, whether they’re impressed or frustrated.”

Netanyahu, who’s clocked 17 non-consecutive years at the top, out-polls all other candidates for the job. And while surveys show that his coalition — the most right-wing in Israel’s history — won’t attract enough votes to form the next government, neither will the opposition.

When the election is held — it’s scheduled by next October — the country risks a repeat of the years 2019-2022, when it was dragged through five ballots while a transitional government with limited authority ran the country. Apart from 18 months of that period, Netanyahu held power.

This week, Netanyahu told parliament that what he has accomplished in the two years since Hamas’ Oct. 7, 2023 attacks, especially by bombing Iran’s nuclear facilities in June, ensures unprecedented national safety.

If his opponents were in charge, he said, “You Members of Knesset, all citizens of Israel without exception — Jews, Arabs, leftists, rightists, ultra-Orthodox, secularists — would all go up in atomic smoke.”

A day earlier, he announced that Israel’s battles against Hamas, Lebanon’s Hezbollah, the Houthis of Yemen, and their sponsor Iran — alongside the collapse of former Syrian President Bashar Assad’s regime — had so boosted the country’s strategic position since 2023 that he’s renaming them the “War of Redemption.”

What he didn’t say, but everyone understood, is that the name applies to his political career as well.

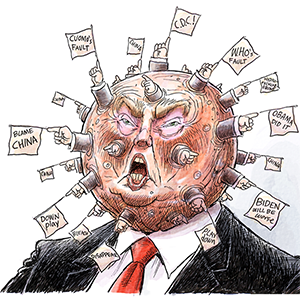

For his critics, who are legion in Israel and abroad, this seems beyond belief. He was in charge on Oct. 7, 2023, the day of Hamas’ attack and the worst single-day in the Jewish state’s history. Indicted by the International Criminal Court for alleged war crimes in Gaza, on trial in Tel Aviv for bribery and fraud, Netanyahu, 76, who denies all the accusations, should be at his political end point.

Sever Plocker, a long-standing commentator at the centrist Yedioth Ahronoth newspaper, wrote this week what many believe — that unless Netanyahu is replaced the country can’t move on. Netanyahu, Plocker wrote, is “one of the most hated statesmen in the world” and “Israel today is more isolated than ever before.”

While Netanyahu got a shot in the arm after the remaining living hostages were released from Gaza, not everyone lays the win at his feet. Trump’s son-in-law and confidant, Jared Kushner, and Middle East envoy Steve Witkoff spoke to families in Tel Aviv’s Hostage Square as exchanges took place. They were hailed for their role in securing the deal, but Witkoff was met with jeers when he tried to credit the Israeli prime minister.

Netanyahu’s handling of the war in Gaza, in which tens of thousands of Palestinians have been killed, humanitarian aid was and continues to be blocked and much of the strip reduced to rubble, alienated many around the world. That derailed Israel’s hopes for the normalization of ties with more Arab and Muslim countries — a major strategic goal at home and in the U.S.

U.S. President Donald Trump hopes to one day persuade Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman to recognize Israel and join the so-called Abraham Accords — one of Trump’s flagship achievements in his first term. The kingdom’s de-facto ruler has so far held off. Publicly, he has set an independent Palestinian state as a precondition — an idea opposed by Netanyahu and his coalition partners.

The economy and businesses have also taken a hit from mass call ups of Israelis for reserve duty. The country’s gross domestic product is still smaller, in shekel and real terms, than it was on the eve of the conflict.

Netanyahu dominates the Likud Party, whose domestic base makes little distinction between fealty to the prime minister and to the party. The opposition, a mix of secular leftists and nationalist hawks, is united only by opposition to him, making it unlikely that an alternative coalition can emerge.

The prime minister’s legal troubles have discouraged most politicians from working with him in recent years, driving Netanyahu into the arms of the ultra-nationalists and ultra-Orthodox with whom he now shares power. That pact holds two key threats to the government: a walkout from far-right partners if Hamas isn’t quickly disarmed and removed from positions of influence in Gaza, and a law exempting the ultra-Orthodox from military conscription.

Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich and National Security Minister Itamar Ben Gvir are skeptical that Trump’s plan for peace in Gaza — announced with great fanfare earlier this month — can bring down Hamas, designated a terrorist group by the U.S. and many others. They have voiced hopes of resettling Gaza with Israeli Jews and annexing the West Bank — which both Trump, and consequently Netanyahu, reject.

The Trump administration is pushing Netanyahu to be patient about Gaza and not return to war. It wants Israel to focus on rebuilding in parts of the strip even if armed Hamas militants are still operating elsewhere.

The conscription of ultra-Orthodox men, also known as Haredim, still lingers over the government. In July, the United Torah Judaism and Shas parties quit government — though stopped short of collapsing it — and are still boycotting votes on any government-proposed legislation, de facto paralyzing the Cabinet and feeding a dynamic that could see it fall apart.

The two parties are unlikely to fully rejoin the government unless a bill exempting most ultra-Orthodox men from military service gets underway. The exemption on religious grounds is unpopular among many voters, including Netanyahu’s base, which wants to see Haredi men share the burden of fighting.

Gila Gamliel, a Cabinet member in his party, said in a radio interview this week, “I believe that the government can serve out its term.”

Few Israeli governments have achieved this, and speculation has been rife that Netanyahu will call early elections to harness the small popularity boost on the back of military gains and the return of hostages from Gaza.

But this week Netanyahu hinted he intends to hold off on elections when he said he wanted to pass the 2026 budget “soon.” In the past, Israeli lawmakers have often blocked the passing of budgets as a way to bring down governments.

Trump gained a great deal of the praise for the ceasefire in Gaza, and he remains a key asset for Netanyahu. Addressing Israeli lawmakers last week, Trump urged President Isaac Herzog to pardon the prime minister.

Strategist Shtrauchler said that wasn’t coincidental.

“Trump effectively launched Netanyahu’s election campaign,” he said. “The prime minister is counting on Trump’s presence moving forward. They are fully coordinated.”

_____

(Chris Miller contributed to this report.)

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments