Gig workers, street vendors and day laborers hit by feds in Chicago immigration crackdown

Published in News & Features

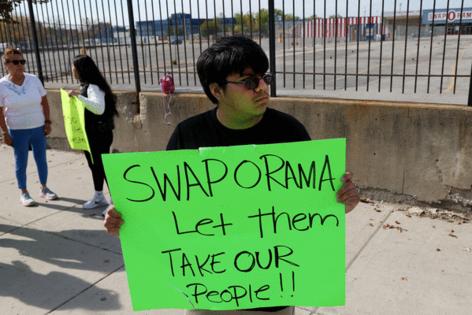

CHICAGO — Five days after armed federal agents descended on the Swap-O-Rama flea market and took more than a dozen people away, some of the market’s vendors were back at work, selling tools, hot sauce and women’s underwear from spaces they rent in the parking lot.

But the flea market was mostly barren on Tuesday’s overcast afternoon. Customers and vendors alike, it seemed, were staying away.

“It’s a hard decision,” to set up shop again at the open-air Back of the Yards market, said one Swap-O-Rama vendor, who gave only her first name, Sylvia. “We don’t like what happened last Thursday, but we have to come.”

Weeks into President Donald Trump’s immigration crackdown in Chicago, that’s a decision some of Chicago’s most vulnerable workers — those who work out in the open, selling tamales on street corners and waiting for construction jobs outside home improvement stores — are making every day.

Over the last seven weeks, federal agents have carried out several raids in a parking lot near O’Hare International Airport where ride-share drivers wait for passengers. They arrested a flower seller in Archer Heights and another street vendor as she sold tamales outside a Home Depot in Back of the Yards. On Wednesday, they detained a cotton candy vendor near 28th Street in Little Village. They detained 13 people at Swap-O-Rama.

So far, large-scale worksite immigration raids, the likes of which were more common during the first Trump administration and for which workers and their advocates have prepared since the beginning of this year, have largely not materialized in Chicago, although the administration has carried them out elsewhere. Instead, many of those being detained have been gig workers or those working independently, particularly those who work outside. Administration officials say they have arrested more than 1,500 people during the Chicago crackdown, which it’s termed “Operation Midway Blitz.”

Workers in the city’s informal economy of street vendors and day laborers are “low-hanging fruit,” for federal agents, said Shannon Gleeson, a professor at Cornell’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations who writes about immigrant workers’ rights.

These workers lack the protections offered by traditional employers, many of whom have caught on to the idea that they can bar agents from their factories or restaurants if they don’t have a judicial warrant, she said.

In Chicago — which Gleeson described as “one of the most organized places on the planet in terms of worker advocacy” — many businesses have posted signs that warn federal agents they won’t be let in without a warrant.

Some employers have taken things a step further: After feds were spotted on 26th Street in Little Village last week, at least two nearby restaurants stationed workers in their entryways to let diners in one by one, relocking the front door after letting customers in.

Immigration agents are “looking to do whatever’s easiest for them,” agreed Miguel Alvelo Rivera, executive director of the Latino Union of Chicago, which organizes with day laborers throughout the city. The group estimates that around 30 day laborers have been detained in the Chicago crackdown.

In Chicago today, these workers must decide whether to show up to work, knowing federal agents are roving the city, or stay home, and risk the ability to pay their bills.

On some Chicago corners, street vendors have disappeared. Many are lying low because they are scared of being detained, said Maria Orozco, development manager for the Street Vendors Association of Chicago. A relief fund for street vendors set up by the organization attracted around 500 applications, Orozco told the Tribune.

Their absence from the streets is a cultural loss and an economic one, she said.

“These people pay taxes, they give back into the economy,” said Orozco, herself the daughter of Chicago street vendors.

People without legal permission to work in the U.S. often turn to various forms of self-employment to make a living. That’s in large part because of a 1986 law that made it illegal for employers to knowingly hire people without permission to work in the U.S.

And some independent workers who have legal permission to work in the U.S. — but who look Latino — also fear going to work and not coming home, advocates say.

In Chicago — where the sight of federal agents chasing people and loading them into unmarked vehicles has become almost commonplace — officials have repeatedly detained people, including U.S. citizens, first, and sought information about them later.

In September, the day the Trump administration announced Midway Blitz, the Supreme Court issued a decision that paved the way for immigration officials to profile people based on their race, the language they speak — or the type of work they do.

“The Fourth Amendment protects every individual’s constitutional right to be ‘free from arbitrary interference by law officers,’” Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in a dissent in that case. “That may no longer be true for those who happen to look a certain way, speak a certain way, and appear to work a certain type of legitimate job that pays very little.”

The Trump administration has argued that it is targeting the “worst of the worst” in its Chicago crackdown.

In response to questions about the Swap-O-Rama raid, for instance, Department of Homeland Security Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin said the agency had arrested “13 illegal aliens who have broken our nation’s immigration laws, with criminal histories that include arrests for DUI, battery causing bodily harm, and domestic violence.”

But Homeland Security didn’t provide the names of those arrested at the flea market after the Tribune asked for them, making it impossible to verify its claims.

Meanwhile, advocates say there is more the city and business owners can do to protect workers in the informal economy, even if they don’t employ them directly.

Alvelo, of the Latino Union, said the group is pushing for the creation of a city-owned structure for day laborers to wait for work, the likes of which has been created in Plano, Texas. He also said Home Depot could bar federal agents from carrying out enforcement actions on company property if they lack a warrant.

In an emailed statement, Home Depot spokesperson George Lane said, “we aren’t notified that the immigration enforcement activities are going to happen, and in many cases, we don’t know that arrests have taken place until after they’re over.”

When asked if the company has a policy to not allow agents onto its private property, he did not directly answer the question but said, “we tell associates to report these incidents immediately and not engage with the activity for their safety.”

At Swap-O-Rama, some called for a boycott on social media after blaming the market’s owner for allowing the feds on property. The market’s co-owner, Ted Joseph, said at the time that an employee had tried to prevent agents from entering.

“One of our people said this is private property and they said to that person, ‘If you resist we’ll arrest you, we’re coming in anyway,’” Joseph said.

And at O’Hare, the Illinois Drivers Alliance — a coalition of unions seeking to organize ride-share drivers — has pushed for security in the ride-share driver lots as well as signs that say that immigration enforcement operations are prohibited on the city-owned property.

Cassio Mendoza, a spokesperson for Mayor Brandon Johnson, said previously that the city believes it could take legal action against the feds for trespassing if they attempted to raid the lot once the signs were posted.

As of Thursday, the signs were up. But federal agents returned to the ride-share lot in the afternoon anyway, according to witnesses on the scene and video reviewed by the Tribune.

Fifteen people were arrested by Border Patrol agents Thursday, the Department of Homeland Security said, describing those detained as “illegal aliens from Colombia, Kurdistan, Mongolia, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Venezuela.”

“The fact of the matter is those who are in this country illegally have a choice,” DHS said. “They can use the CBP Home app and receive a free flight and a $1,000 check or they can be arrested, detained, and deported.”

Mendoza did not respond to a question about whether the city would take legal action. Then on Saturday afternoon, feds were spotted at the lot yet again, arresting around 10 more people, according to the Drivers Alliance.

After Thursday’s raid, cars apparently belonging to detained ride-share drivers sat abandoned near the lot’s entrance, according to video reviewed by the Tribune.

Mario Salmeron, a tow truck driver, said the wife of a detained ride-share driver called him crying Thursday asking him to tow her husband’s car.

So Salmeron towed the man’s Toyota Corolla back to his northwest suburban home.

The call from the man’s wife, he said, broke his heart.

“God bless every American,” Salmeron said. “Every single person.”

___

Chicago Tribune’s Gregory Royal Pratt and Stacey Wescott contributed.

____

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments