Should medical marijuana be less stringently regulated? A drug policy expert explains what’s at stake

Published in News & Features

Medical marijuana could soon be reclassified into a medical category that includes prescription drugs like Tylenol with codeine, ketamine and anabolic steroids.

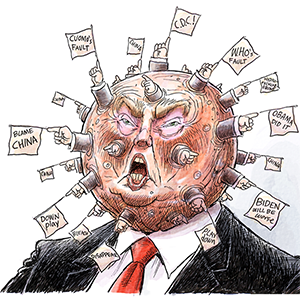

That’s because in December 2025, President Donald Trump signed an executive order to reschedule marijuana to a less restricted category, continuing a process initiated by President Joe Biden in 2022.

Currently, marijuana is in the most restrictive class, Schedule I, the same category as street drugs like LSD, ecstasy and heroin.

For years, many researchers and medical experts have argued that its current classification is a hindrance to much-needed medical research that would answer many of the pressing questions about its potential for medicinal use.

In January 2026, Republican Senators Ted Budd, of North Carolina, and James Lankford, of Oklahoma, introduced an amendment to funding bills trying to block the rescheduling, claiming that it “sends the wrong message” and will lead to “increased risk of heart attack, stroke, psychotic disorders, addiction and hospitalization.”

As a philosopher and drug policy expert, I am more interested in what is the most reasonable marijuana policy. In other words, is rescheduling the right move?

Broadly speaking, there are three choices available for marijuana regulation. The U.S. could keep the drug in the highly restricted Schedule I category, move it to a less restrictive category or remove it from scheduling altogether, which would end the conflict between state and federal marijuana laws.

As of January 2026, cannabis is legal in 40 of 50 states for medical use and 24 states for recreational use. Rescheduling would only apply to medical use.

Let’s examine the arguments for each option:

The Controlled Substances Act places each prohibited drug into one of five “schedules” based on proven medical use, addictive potential and safety.

Drugs classified as Schedule I – as marijuana has been since 1971, when the Controlled Substances Act was passed – cannot be legally used for medical use or research, though an exception for research can be made with special permission from the Drug Enforcement Administration. Schedule I drugs are believed to have a high potential for abuse, to be extremely addictive and to have “no currently accepted medical use.”

As a Schedule I drug, marijuana has been more tightly controlled than cocaine, methamphetamine, PCP and fentanyl, all of which belong to Schedule II.

Some policy analysts and anti-marijuana activists argue that marijuana should remain a Schedule 1 drug.

A common objection to rescheduling it is the assertion that 1 in 3 marijuana users develop an addiction to the drug, which stems from a large study called a meta-analysis.

A careful reading of that study reveals the flaws in its conclusions. The researchers found that about one-third of heavy users – meaning those who use marijuana weekly or daily – suffered from dependence. But when they looked at marijuana users more generally – meaning people who tried it at least once, the way addiction rates are normally measured – they found that only 13% of users develop a dependency on marijuana, which makes it less habit-forming than most recreational drugs, including alcohol, nicotine and caffeine, none of which are scheduled under the Controlled Substances Act.

Further, if the 1-in-3 figure were accurate, then marijuana would be more addictive than alcohol, crack cocaine and even heroin. This defies both common sense and well-established studies on the comparative risk of addiction.

Critics of rescheduling also deny that there is convincing evidence that marijuana or its compounds have any legitimate medical use. They cite research like a 2025 review paper that assessed 15 years of medical marijuana research and concluded that “evidence is insufficient for the use of cannabis or cannabinoids for most medical indications.”

This claim is problematic, however, given that the Food and Drug Administration has already approved several medicines that are based on the same active compounds found in marijuana. These include the drugs Marinol and Syndros, which are used to treat AIDS-related anorexia and chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Both of these contain delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, the substance that is responsible for the marijuana high.

If the active ingredients of marijuana have legitimate medical use as established by the FDA, then it stands to reason that so must marijuana.

Moving marijuana to schedule III would make it legal at the federal level, but only for medical use. Recreational use would remain federally prohibited, even though it is legal in 24 states as of early 2026.

The most obvious benefit to rescheduling, noted above, is that it would make research on marijuana easier. The system of cannabinoid receptors through which marijuana confers its therapeutic and psychoactive effects is crucial for almost every aspect of human functioning. Thus, marijuana compounds could provide effective medicines for a wide variety of ailments.

Contrary to the 2015 review mentioned earlier, studies have shown that cannabis is effective for treating nausea and AIDS symptoms, chronic pain and some symptoms of multiple sclerosis, as well as many other conditions.

Rescheduling could also improve medical marijuana guidance. Under the current system, medical marijuana users are not provided with accurate, evidence-based guidance on how to use marijuana effectively. They must rely on “bud tenders,” dispensary employees with no medical training whose job is to sell product. If cannabis were moved to Schedule III, doctors would be trained to advise patients on its proper use. On the other hand, medical schools need not wait for rescheduling. Given that many people are already using medical marijuana, some medical experts have argued that medical schools should provide this training already.

Rescheduling, however, is not without complications. To comply with the law, medical marijuana programs would have to start requiring a doctor’s prescription, just like with all other scheduled substances. And it could be distributed only by licensed pharmacies. That might be a good thing, if marijuana is as dangerous and addictive as critics claim. But advocates of medical marijuana might be concerned that this would increase costs to the consumer and restrict access. That concern might be mitigated, however, if health insurance companies are required to cover the costs of medical marijuana once it is rescheduled.

In addition, it is unclear how rescheduling would affect state-level bans on medical marijuana. Generally speaking, states cannot legally restrict access to pharmaceuticals that have been approved by the FDA. However, this principle of federal preemption is currently being challenged by six states claiming they have the authority to restrict access to the abortion medication mifepristone.

The debate over rescheduling ignores a third option: that marijuana could be removed entirely from the Controlled Substances Act, giving states the authority to allow medical marijuana to be distributed without a prescription.

Some of the objections to rescheduling come from marijuana advocates. Given that marijuana is safer and less addictive than alcohol – which is not scheduled under the Controlled Substances Act – a case could be made for removing it entirely from the list of scheduled substances and allowing states to legalize it for recreational use, as many states have already.

In fact, many drugs as, or more powerful than, marijuana are also not scheduled. For example, most over-the-counter cough medicines contain dextromethorphan, a hallucinogenic dissociative, which in large doses causes effects similar to PCP.

Removing marijuana from the list of controlled substances would also decriminalize the drug. Over 200,000 Americans were arrested for marijuana in 2024, over 90% of them for mere possession.

At the moment, the third option seems very unlikely. Although over 60% of Americans are in favor of full marijuana legalization, it lacks support in Congress.

Medical marijuana rescheduling looks likely to occur in 2026. After all, it has been proposed by both Biden and Trump. Whether it is the right move, only time will tell.

This article includes portions of a previous article originally published on Oct. 9, 2024.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Chris Meyers, George Washington University

Read more:

DEA could reclassify marijuana to a less restrictive category – a drug policy expert weighs the pros and cons

26 states may soon need to regulate cannabis – here’s what they can learn from Colorado and Washington

CBD, marijuana and hemp: What is the difference among these cannabis products, and which are legal?

Chris Meyers does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments