7 inmates died in Maryland state prisons in 2 months. Why?

Published in News & Features

Maryland correctional authorities have recorded seven inmate deaths over the past two months, a pattern that criminal justice experts say points to deeper challenges inside the state’s prisons.

“The number of deaths raises more than individual problems. It is time to look at systemic shortcomings,” said Nora Demleitner, a past president of St. John’s College in Annapolis and a longtime criminal justice scholar who has written extensively on sentencing and corrections policy.

“Staffing shortages and/or overcrowding usually contribute to deaths in custody, often combined with insufficient medical coverage,” she said.

Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services officials say staffing levels and access to services have improved in recent years, even as scrutiny continues over conditions inside Maryland’s correctional facilities.

DPSCS spokesperson Ioannis Varonis said the agency’s vacancy rate for correctional officers was nearing 17% in 2023, when Gov. Wes Moore took office and Secretary Carolyn Scruggs began her tenure. Through targeted recruitment, streamlined hiring and retention efforts, the vacancy rate has since dropped to 8.42%. The current figure represents the lowest vacancy rate reported by DPSCS in the past seven years, Varonis said. In 2025, the department also hired more correctional officers than in any other year over the last decade.

Department officials say incarcerated individuals have access to services, including treatment from licensed mental health professionals, substance use disorder programs, and counseling, to improve safety and address underlying behavioral and health needs. The agency has also been working with AFSCME, the correctional officers’ union, on an analysis that reviews current staffing levels and identifies areas where additional posts may be necessary.

“We now look forward to working with AFSCME on completing that analysis and — based on the final analysis — changes to staffing levels may be implemented to improve the safety of our staff and the incarcerated population in their care,” Varonis said.

Last year, deaths of people in custody at Maryland state prisons reached a four-year high, according to the Governor’s Office of Crime Prevention and Policy, which tracks the data under the federal Death in Custody Reporting Act. The 68 state prison deaths reported for 2025 include 21 deaths of natural causes, eight homicides and 34 deaths whose classification was pending.

The resolution of pending cases could ultimately increase the homicide count. According to the Maryland State Police, 13 state prison inmate deaths last year were investigated by the agency’s homicide unit.

Three of the seven recent deaths occurred at the Jessup Correctional Institution.

On Jan. 19, 33-year-old Joseph Harrell was pronounced dead there following an altercation with another inmate near the prison library, according to Maryland State Police. Authorities said a suspect has been identified, but no charges have been filed.

On Jan. 18 at Jessup, 38-year-old Javon Foster was found in his cell and pronounced dead. On Dec. 13, 23-year-old Deon Smith Jr. died under what police described as suspicious circumstances.

Three days later, Wenhui Sun, 36, died at the Maryland Correctional Training Center in Hagerstown following what investigators said was an altercation involving three inmates.

At North Branch Correctional Institution in Cumberland, two inmates died: 32-year-old Jordan Polston on Dec. 23 and 51-year-old Larry Horton on Jan. 10.

Data obtained from the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner show that the cases involving Foster and Sun remain pending, meaning the cause and manner of death have not yet been determined. Four other deaths — Harrell, Smith, Polston and Horton — are listed as homicides and part of ongoing investigations.

Staffing issues

Demleitner said staffing shortages can create a cycle of poor conditions.

“Staff shortages tend to lead people to resign, which makes the situation worse for remaining staff,” she said. “There isn’t the time to train and educate staff or for them to spend with prisoners to understand the dynamics and diffuse them.”

DPSCS data shows the agency employs about 9,220 people and oversees roughly 17,875 incarcerated individuals, making it one of the state’s largest agencies. About 8% of its workforce left in 2024, and nearly 500 correctional officer positions were vacant as of mid-2025, according to a government-funded Safe Inside project report.

The American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees Trade, the union for corrections officers, could not be reached for comment.

Jarrod Smith, a national trial attorney with the criminal defense firm Smith & Vinson, said supervision gaps often play a central role in inmate violence.

“The biggest issue seems to come from staffing and supervision problems,” Smith said. “We are seeing a direct correlation between personnel shortages and the rise in violence. High-risk areas like libraries and dining halls need a consistent, trained presence at all times.”

Tools for reducing violence

Demleitner said models such as “Restoring Promise,” a Vera Institute initiative that addressed “harmful prison practices and policies” through collaborative research, narrative change, and technical assistance, which emphasize communication and mediation over strict punishment, have shown promise in lowering incidents in some correctional systems.

“When you create a culture of communication rather than just lock and key, violence drops,” she said. “These programs train both staff and inmates to mediate disputes before they escalate to physical confrontation.”

She added that expanding access to cognitive behavioral therapy could help inmates develop de-escalation skills, though those programs are often among the first to be cut when budgets or staffing levels are strained.

Separating inmates more effectively, rather than relying on solitary confinement, is another area experts say needs improvement.

“Separation is a double-edged sword,” Demleitner said. “We don’t need more solitary confinement; we need smarter classification. We need data-driven systems that separate security threat groups and place predatory individuals away from vulnerable ones.”

Varonis said the DPSCS does not use what it defines as solitary confinement, “a form of extreme isolation historically marked by minimal human contact and movement.” Instead, the department uses restrictive housing, in which incarcerated individuals are housed with another person whenever possible and are permitted out-of-cell time and activities, though those privileges may be limited.

Demleitner noted that the first days of incarceration are often the most dangerous, making intake screening critical for identifying past conflicts, gang affiliations and mental health crises.

“There is always a lead-up to violence,” Demleitner said. “Shifting group dynamics, sudden ‘clumping’ of certain groups or an unusual quiet can signal that something is being planned.”

Medical issues

On the medical side, particularly in mental health care, Demleitner said, limited funding can reduce access to diagnosis and treatment, increasing the risk that physical harm or psychological distress goes unnoticed.

A spokesperson for the DPSCS said incarcerated individuals have access to licensed mental health professionals, substance use disorder treatment, counseling services, and peer-support and self-help programs throughout the state’s correctional system. The department also offers rehabilitation, education and reentry-focused programs, including anger-management, alternatives to violence and victim impact counseling, aimed at addressing behaviors and conditions that can contribute to harm inside facilities.

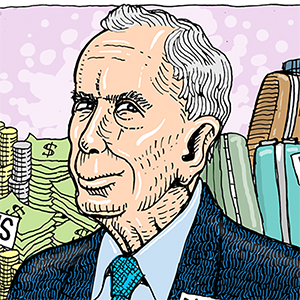

Despite several violent incidents, not all inmate deaths stemmed from assaults. George Kenney, 69, died Dec. 27 at the Harford County Detention Center after repeated hospital visits related to cardiac issues, according to the Harford County Sheriff’s Office.

Last month, the ACLU and NAACP filed a lawsuit, alleging a “deadly pattern of abuse” at the Harford County Detention Center, which the organizations say has led to more than 20 suicide attempts since 2019. The suit — filed against Sheriff Jeff Gahler, Warden Daniel Galbraith, Harford County and the state — says there is deficient screening and treatment at the detention center, “excessive” reliance on isolation, deficient monitoring of those identified as suicidal or needing medical attention, and punishment in response to those who are suicidal.

Officials with Harford County declined to comment on the pending, active litigation.

Next steps

Maryland lawmakers passed legislation in 2025 requiring state officials to notify elected leaders when an inmate dies in custody, a move aimed at increasing transparency. Advocates, however, say stronger oversight is needed.

“There needs to be a correctional ombudsman with the power to conduct unannounced inspections and hold administrators accountable for safety lapses before they become fatal,” Smith said.

Demleitner said the number of in-custody deaths underscores the need for sustained investment, rather than short-term fixes.

“Without enough trained staff and adequate medical and mental health coverage,” she said, “the system remains reactive instead of preventative — and that’s when tragedies continue to happen.”

_____

©2026 Baltimore Sun. Visit baltimoresun.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments