Column: Amelia Earhart soars back into the headlines in new book 'The Aviator and the Showman'

Published in Books News

Where’s Amelia?

We’re still looking, though recent events seem to offer the possibility, the possibility I emphasize, that we may find out what happened to aviatrix Amelia Earhart, who, along with navigator Fred Noonan, vanished in their twin-engine Lockheed Model 10E Electra as they attempted to fly around the world.

Here’s a recent report from Travel Noire: “U.S. researchers have announced a new mission to locate Amelia Earhart’s lost plane. … The expedition … follows compelling satellite imagery that potentially shows parts of Earhart’s Lockheed Electra 10E protruding from the sand on Nikumaroro, a remote island in Kiribati, approximately 1,000 miles from Fiji.”

We shall see. But this “news” has popped Earhart back into the news.

She vanished in 1937, 88 years ago if you’re counting, and few mysteries have been as durable, few people as eternally alluring as Earhart. You would be hard-pressed to find a contemporary comparison to match her.

She has an official agent and website. Hilary Swank played her in a movie. There have been many books. And there’s Amelia Earhart Elementary School at 1710 E. 93rd St. in the Chicago's Calumet Heights neighborhood.

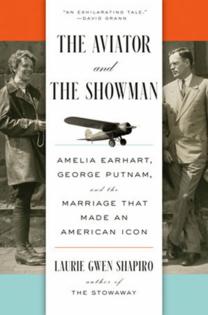

Also an exciting new book, “The Aviator and the Showman: Amelia Earhart, George Putnam, and the Marriage that Made an American Icon” by Laurie Gwen Shapiro. Set for formal publication on July 15, it has already created a buzz, with a lengthy excerpt in The New Yorker magazine and a number of favorable reviews. David Grann, the author of such bestsellers as “The Wager” and “Killers of the Flower Moon,” says the book is “an exhilarating tale of the adventurous life of Amelia Earhart and the remarkable relationship that helped to forge her legend … stripping away the myths and revealing something far more profound and intricate and true.” Publishers Weekly calls it a “nuanced reprisal of Earhart’s life (that) certainly tarnishes her reputation, but thereby makes her saga all the more captivating.”

And makes the story of her husband all the more disgusting.

His name was George Palmer Putnam, who had published aviator Charles Lindbergh’s hugely successful life story before he met Earhart. On the prowl for another such novelty and hero, he glommed onto her, taken by her modest accomplishments but also her physical attractiveness and charisma.

He wooed her and he promoted her. He’s the one who gave her the “Lady Lindy” tag and further cemented their relationship by having her write her own book, tour the country in her own plane, give hundreds of interviews, embark on a lecture tour, serve as the “aviation editor” of Cosmopolitan magazine and endorse all sorts of products, including cigarettes.

Smart he was, shrewd too. And a master manipulator who left his own wife to marry Earhart. (And, unusually for the time, Earhart did not adopt Putnam’s last name). No question he pushed her but did he push her too far?

Read the book. But know that you will find a man about whom writer Gore Vidal, whose father was a partner with Putnam and Earhart in an aviation venture, said, “I never knew anyone who liked Putnam. It was quite interesting. Everybody who knew him disliked him. Some people disliked him and found him amusing and some people disliked him and found him unamusing.”

Certainly, many of you know some basics of Earhart’s life and a few know of her local connections, even though she wasn’t here long.

Born and raised in Kansas in 1897, she and her family moved around a bit before coming here in 1914. Her father, Edwin, was a lawyer with a dangerous relationship with booze, and her mother, also named Amelia but called Amy, was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. So, in 1914, Amy and her two daughters (Amelia and Muriel) came to Chicago at the invitation of friends and lived in the Beverly neighborhood home of their friends. Amelia, soon to begin her senior year, found the chemistry lab at nearby Morgan Park High School looked “just like a kitchen sink.” So she traveled north to spend her senior year at the highly regarded Hyde Park High School, graduating as a member of the class of 1915.

She did little to distinguish herself — no activities noted in the yearbook — and then it was off to college. She worked as a social worker and got hooked on airplanes. She had her first flying lesson early in 1921 and, in six months, bought her first plane.

In 1928, she was asked to be a passenger with male aviators on a flight across the Atlantic Ocean, emphasis on passenger. Together with pilot Bill Stultz and co-pilot Louis Gordon, she flew in the airplane Friendship, acting as navigator on the flight. On June 18, after 20 hours of flying, they landed in Wales and she became the first woman to cross the Atlantic by air. Acclaim was fast and furious.

After lively visits to New York City and Boston, she came here and the celebrations and events were all but overwhelming. She visited Hyde Park High School, where a band played “Back in Your Own Back Yard”; spoke at the Union League Club and at Orchestra Hall; was cheered by large crowds as she was paraded through the Loop; heard about Mayor Thompson’s idea for a lakefront airport to be named Amelia Earhart Field.

Headlines blared: “Old Hyde Park School Friends Fete Girl Flyer.”

Earhart spoke: “I’ve always loved Chicago.”

Famous forever for being lost, there is no denying that she was an inspiration for self-determined feminists and everyday daredevils, but I now think of her also as shy and vulnerable, a victim of shrewd manipulation by a slick operator.

Doris Rich, author of “Amelia Earhart: A Biography,” published by the Smithsonian Institution in 1989, has said, “The one thing that she really feared was that nothing would happen. She had to have an important life, and that meant you had to have adventure.”

That she did, but at what cost?

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments