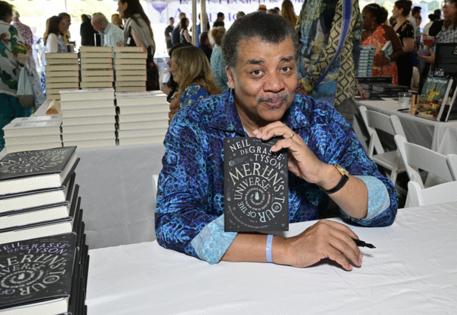

Why Neil deGrasse Tyson says we're falling into science illiteracy

Published in Books News

In October 1995, astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson hadn’t yet become the pop culture science star he is today.

Tyson was newly appointed as the interim director of the Hayden Planetarium in New York City, where as a 9-year-old from the Bronx, he’d first seen the stars and glimpsed his future career.

Then the first exoplanet was discovered, and NBC Nightly News sent a camera crew to interview him as an expert on the discovery and what it meant to have finally found a distant planet around a far-off star.

“I have my best professorial answer,” Tyson says in a recent interview on the patio of a West Hollywood hotel while in Southern California for a few days. “I said, ‘A planet does not orbit the star; they both orbit their common center of gravity.’

“Which means the star does a little jiggle” – he demonstrates with an Elvis-like hip swivel – “while the planet goes around.”

Tyson gave them more scientific explanations of how that led to the discovery and then called friends and family to let them know he’d be making his national news debut that night.

“And that evening, all that ended up on the screen was me jiggling my hips,” he says. “I said, ‘Oh, they visited me. They don’t want my professorial reply. They want a reply that will work in their world.’”

An insight hit him like an apple to Sir Isaac Newton’s head. Tyson got right to work.

“I went home, I stared at the mirror,” he says. “I had my wife just scream out – not scream, but chant out topics, places, things in science and in the universe, and I would deliver a three-sentence reply.

“The sentence has to be informative, ideally humorous, and tasty so that you want to tell someone else,” Tyson says. “I worked at it.

“We can test it now,” he offers, turning to his book publicist and asking her to pick a person, place or thing.

“Taylor Swift,” she replies – it’s just hours before the release of Swift’s “The Life of a Showgirl” album.

“No!” Tyson laughs. “No. About the universe.”

“She is my universe,” his publicist replies to more laughter. “OK, let’s go black holes.”

Before the laughter stops, Tyson is talking.

“Black holes. Avoid them,” he says. “If you see one coming, run the other way. It’s a region of space where the gravity is so strong light can’t even get out, and that’s the fastest thing we know.

“So if you fall in, you’re not coming out. And if light’s not coming out, it’s black. So it’s the best-named thing in the universe. A black hole.

“That’s a soundbite,” Tyson continues. “A little funny, makes you chuckle. It’s all accurate science. I’m not going on an off-ramp to tell a joke. It’s all contained. So I can do that with almost anything.”

Tyson had come to Los Angeles to talk about the publication of a revised edition of his 1998 book “Just Visiting This Planet.” It’s a follow-up to “Merlin’s Tour of the Universe,” which was also recently revamped for the 21st century, with Tyson answering questions about astrophysics from the public in character as Merlin, an all-knowing space traveler whose scientific chops are equaled by his sense of humor.

In an interview edited for length and clarity, Tyson discussed why it was time to update the books, how he first in love with the billions of unreachable stars and planets in the universe, what is so important about the fight for science and discovery, and more.

Q: When did you realize you had a talent for science soundbites?

A: I was invited to be on “The Daily Show with Jon Stewart.” I’d seen the show; we all know the show. He’s smart, he’s witty, he’s clever. Politicians that come on, they want to give their stump speech, and he’s just running circles around them. I said that is not going to happen to me.

So with a stopwatch, I timed the average duration of how long someone speaks before he comedically interrupts. It ranges between 8 and 12 seconds. It doesn’t sound like much, but in banter, that’s a long time. So I went in there loaded. I speak, he jumps in with his joke, we continue, there’s nothing dangling there.

Afterwards, people came up to me and said, “You have such good chemistry with Jon Stewart!” They have no freaking idea what was invested in that. People say, “You’re such a natural.” Is it a compliment or an insult? Maybe a little of both. They’re assuming I didn’t work at it.

Q: They don’t know about your stopwatch at home.

A: Right, right, they don’t know. It’s nonetheless a compliment to say it’s natural. So when did I realize I had the talent? I don’t think of talent. Talent is this fiction of some people are better at some things than other, and we call it talent. Talent often refers to people who are good at something who didn’t try. But in almost all cases, if you part the curtains, they were trying.

Q: So how much is new in the book? Why was it time for a revision?

A: The original selections were questions of high shelf life. They asked about how science works and what the universe is about. In terms of content, there wasn’t much that needed to be changed, but a lot needed to be updated. [Note: Tyson pulled many of the questions from the Merlin Q-and-A column he wrote at StarDate magazine.]

As an example, in the original “Merlin,” there were many questions about Halley’s Comet [which had just appeared a few years earlier]. Now it’s not until 2061, so I removed some questions, just because no one cared anymore.

And there were other questions that could be fleshed out with greater knowledge. For example, someone asked about what the largest telescope in the world would see. At the time, that was a very different telescope than today.

Q: Why’d you name him Merlin?

A: The column predated me for the magazine it appeared in. It was Q-and-A. They didn’t do anything with the Merlin name. It was just a straight Q-and-A and I thought that was so boring. I created Merlin to be kind of witty, a little quirky, playfully irreverent. I found that to be a fun exercise to build the kind of personality this character has.

And since Merlin has been around for the history of civilization, when Merlin recalls conversations with famous figures another fun part was to research how people communicated back then and what words they would have used.

The conversations are authentic in that sense. When Merlin chats with Leonardo da Vinci they’re in a piazza in Florence where he spent time and where they might have been. There are rumors of what his favorite food was. I think it was minestrone soup. So he’s slurping a bowl of minestrone while talking.

Q: Are there common topics people often asked about?

A: Yeah, so there’s black holes, there’s the Big Bang, there’s search for [extraterrestrial] life. These are playful, curious people looking up every now and than [at the stars].

Q: Like the guy wondering what would happen if while he held a black hole at his waist he dropped it on the floor?

A: People ask crazy questions. [He laughs] So I’m going to stay with [him] here. Is it a black hole-proof pocket? The fun part is taking someone’s question that might be a little quirky but still address it with serious science. You accept the premise and take it from there. These are intellectually curious people who had some downtime.

Q: One says he and his friend were bored after dinner, so they did some calculations about energy –

A:– how much energy does Earth have in its motion compared with the equivalent amount of gasoline? That’s the sun, and I’m happy to adjudicate over geeky arguments.

Q: It’s a way for people to get their heads around the science wrapped inside the anecdote.

A: I would say it even stronger than that where it’s a way to find ways that science can matter to people. If it plugs into their curiosity, even if their curiosity is a bit quirky or a bit odd, you still run with it. Taking them very seriously matters and also the pop culture references.

One of my favorite ones in there is the one about Superman flying backwards around the Earth. If you saw the film, you’d remember that he turns back time. I’ll give him that. But the ocean is not connected to the solid Earth.

So if he stops the Earth, the oceans keep moving, just as you keep moving in a car without a seat belt. And saving Lois Lane, he kills a billion people [as the oceans rush over the continents].

Q: Let me ask you about your earliest interest in science and astrophysics. You went to the planetarium on a school trip at 9?

A: It was the night sky. New Yorkers don’t have a relationship with the night sky. There are the tall buildings. Back then, there was air pollution, and light pollution especially. You look up there’s a building in the way. No one thinks about or cares about the night sky.

And I go to my local planetarium, Hayden Planetarium. They dim the lights, and the stars come out. Oh my gosh! I thought it was a hoax. I’ve seen the night sky from the Bronx and it doesn’t have this many stars. I’ll go along with them. Let them think I’m taken in by it.

So yeah, from age 9 onwards. It would take a couple of years ’til I was 11, 11 and a half, before I would realize that you can make a career of this. [Tyson was named permanent director of the Hayden Planetarium in 1996, and director of the Rose Center for Earth and Space, which includes the planetarium since it opened in 2000.]

Q: A lot of kids would have grown out of it, like it was just a phase.

A: I thought about this a lot. If I had grown up on a farm where every night was a perfectly clear sky, then there’s no way I would have become starstruck by it. It would just always be there, and I wouldn’t think of it as anything different or special.

There was a moment between [the age of 9] and 11 or 12 I would end up having access to binoculars. I looked at the moon; the moon was completely better in binoculars. It wasn’t just bigger, it was like you can see texture. Mountains, valleys, craters, shadows. The moon when I first looked at it with binoculars became a world to me.

You call something a world, you think and feel differently about it. It’s like maybe that’s a place to go. A place to hang out.

Q: We’re in a period now where funding is being slashed for science and education and many people don’t care. If people aren’t aware of the importance of science, what’s going to get lost?

A: So you’re telling me I suck at my job? [He laughs] You’re telling me I’m failing badly? Say it, just say it. No one cares about science and that’s been my whole mission to get people to care about science.

Q: No, no, but so many things are in peril compared to the support excitement around the ’60s, the space shuttles, the Hubble and Webb telescopes. Are we going to keep having these kinds of huge successes?

A: No.

Q: That’s not your fault.

A: I assume you want a fleshier answer than just a no.

Q: Yeah, I’ll take a three-sentence soundbite.

A: Yeah, I can’t soundbite this one. So maybe science is a victim of its own success. It is so seamlessly blended into your daily life. If anyone had any clue how much science, engineering and technology went into the iPhones. They’re always, “Oh, it was Steve Jobs.” No.

How many patents are in it? How many branches of success are represented in it? We needed somebody to bring it together, but it’s got to be there to bring together in the first place.

Q: So what’s going to happen to science and funding going forward?

A: It looks to me like it’s going to get worse before it gets better. It will get so bad we will wonder why other countries will have these major advances that we don’t as we sink deeper into the science-illiterate hole that we’re digging for ourselves. And at the bottom of that hole, everybody’s going to look at each other across the aisle and say, We’ve got to do something.

Then we’ll be united and rise up out of the hole in reaction to those failures. And why do I have confidence in that? Because we’ve done it multiple times before.

Q: What would be an example?

A: October 4, 1957. “Oh my gosh, the godless communists are ahead of us technologically, and Sputnik went over our country.” We are freaking out. Kennedy addresses a joint session of Congress in 1961, six weeks after Yuri Gagarin came out of orbit. We didn’t have a ship that wouldn’t blow up on the launch pad that could carry a person yet.

It’s the speech where he says we’ll put a man on the moon and return him safely to Earth before the decade is out. Stirring words, but that’s not what made it happen. It was the two paragraphs before in the same speech, which you don’t see anywhere. That the events of recent weeks are any indication of the impact of this adventure on the minds of men everywhere, then we need to show the world the path of freedom over the path of tyranny.

It was a battle cry against communism. That’s what wrote the checks. From being less than zero, we reacted. There was no partisan bickering, not over that.

Q: And now we’re talking about going to the moon again.

A: Do you know why we’re going back to the moon now? We could have stayed there in 1972. Could have gone in 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010. What happens? 2015. China says they’re going to put taikonauts, the Chinese astronauts, on the moon. Then we say, “Oh, wouldn’t it be nice if we went back to the moon? Look at the time. It’s time.”

So under the guise that we’re just being explorers again, behind the scenes we’re reacting to a perceived or real threat. We are very good at reacting. To be proactive, you have to foresee what could happen and then prevent it. But we’re not good at that. We’re too busy arguing over other things.

©2025 MediaNews Group, Inc. Visit ocregister.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments