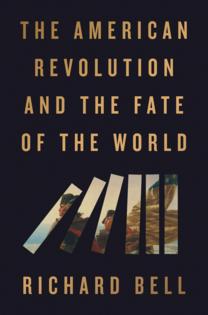

Review: Book says the American Revolution was really a world war

Published in Books News

Next July marks 250 years since a handful of upstart American colonies declared independence from Britain. A war was fought, as we all know, and almost immediately after it was over, Richard Bell asserts in “The American Revolution and the Fate of the World,” a “collective amnesia” took hold.

The preference for historians and Americans alike was to tell a simple story, one in which “plucky homegrown heroes faced down all the king’s horses and all the king’s men, all on their own.” The truth is, Bell says, the country’s founding required “a world war in all but name.”

The transnational nature of the conflict can’t be understated, he goes on. Its reach was felt far and wide, so much so that it is “not an exaggeration to say that the American Revolution set much of the world as we know it in motion,” to the delight of some and the horror of others, namely Indigenous and enslaved peoples.

To get at that immensity, Bell advances seven core arguments that encompass migration, the war’s human cost, the improbability of its outcome, naval power, trade, imperial crackdowns in other colonies and the spread of liberty. He then filters it all through individual experience — Molly Brant, for instance, a Mohawk woman who worked as a broker, spy and refugee-camp coordinator. It’s a crackerjack way to illustrate the heart of the conflict and its scope.

The choicest bits are the unexpected details, such as a man cutting off his son’s trigger finger so he wouldn’t have to go to war; author Washington Irving basing his headless horseman on the feared Hessian mercenaries hired by the British; or an Indian king commissioning a life-size automaton of a tiger mauling an East India Company soldier. When the automaton’s handle was cranked, the soldier’s “wheezing death throes” could be heard.

The book’s tone can be uneven, however. Bell’s occasional colloquialisms prove welcome — such as when British Admiral Sir George Rodney “made out like a bandit” after ransacking a Caribbean island on behalf of Britain — but his awkward direct addresses, not so much.

“Our purpose here will be to examine the many myths about that winter at Valley Forge. … Our guide will be [Baron von] Steuben,” he writes at one point. Or later when he makes it “our task” to understand the French alliance beyond the contribution of the Marquis de Lafayette.

Moreover, Bell sometimes strains to make revolutionary connections, most particularly in the implication that America’s refusal to allow Britain to send home-grown prisoners to its shores was the reason Australia became a penal colony. The truth, Bell does admit, is that none of Britain’s colonies wanted its prisoners — the number of which had reached critical proportions — and yet he still links the deportations to the colonists’ fight for independence.

Despite that, Bell — who is British by birth but an American by choice — is an apt guide for readers revisiting “the shot heard round the world” and its ramifications. His “The American Revolution and the Fate of the World” is a solid addition to any semiquincentennial reading list.

____

The American Revolution and the Fate of the World

By: Richard Bell.

Publisher: Riverhead Books, 406 pages.

©2025 The Minnesota Star Tribune. Visit at startribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments