Review: 'Canticle' immerses readers in 13th-century mysticism

Published in Books News

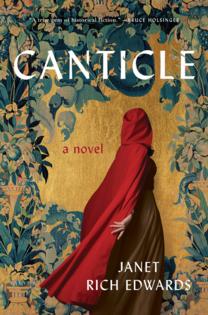

The cover of “Canticle” depicts a woman in a vibrant red, hooded cloak swirling away from the reader.

It hints at what’s inside: a mystical story that immerses us in an earlier century, in the vein of Lauren Groff’s "Matrix" or Sue Monk Kidd’s "The Book of Longings.“ If you loved either of them, as I did, you might have a hard time putting down “Canticle.”

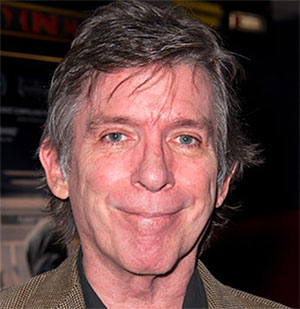

The author, Janet Rich Edwards, is a professor of epidemiology at Harvard Medical School — not the typical background for a novelist writing about medieval women mystics. But she says on her website that after writing more than 300 papers for scientific journals, she wondered “if she could convey more truth, or at least different truths, through story.” And “Canticle” is quite a story.

Aleys, the protagonist on the cover, lives in a village near Bruges (Brugge in Dutch) in what is now Belgium. The novel begins in 1295, when at age 16, Aleys loses her beloved mother, who dies in childbirth (side note: Rich Edwards researches women’s health). The deeply religious wool-maker’s daughter yearns to read her mother’s treasured psalter (the Book of Psalms) in Latin. She can read in Dutch and befriends Finn, a dyer’s son, who teaches her Latin, in exchange for her teaching him to read. After hearing a visiting friar read a Latin verse about love, she persuades Finn to locate a copy of the Canticle (finally, we get to the book title!), “the most beautiful, the most poetic psalm.”

But when Finn joins a monastery and her father wants her to marry an older merchant, Aleys flees, ending up at a community of religious women, the beguines. They refuse to answer to the Pope — Boniface VIII at the time — much to the ire of the local bishop, who calls them “self-righteous burrs beneath his saddle.” The bishop suspects one of these women has been translating scripture into Dutch, a scandalous idea that would allow people to read their Bibles without a priest: “Heresy breeds where butchers read the Bible.”

Aleys isn’t the translator but she does believe she’s been chosen by God for a higher purpose and is impatient to be “shown her gift.” Soon she is.

While praying over a dying boy at the hospital, she feels a buzzing in her hands. Rich Edwards’ descriptive writing is lyrical and lovely, as evidenced here: “She bleeds into the boy and he bleeds into the prayer, and the prayer beats with his heart and she breathes the prayer.”

Aleys emerges from a trance to find the boy healed. Townspeople begin calling her “Sint” (saint) and it’s not long before the bishop decides he can use Aleys’ gift to his advantage. It’s not giving too much away to note that the bishop and other men in the church hierarchy do not come off well in “Canticle.” The book’s women, on the other hand, are full of surprises.

You don’t need to be religious to appreciate this novel, but you might get more out of it if you have a basic Biblical knowledge. I also found myself looking up more about the beguines and anchoresses, fascinated by the thought of someone choosing to live a solitary life, locked in a cell connected to the church. Finally: You should be open to the idea of miracles.

“Canticle” is an auspicious debut — and hopefully not the last novel we’ll read from Rich Edwards.

____

Canticle

By: Janet Rich Edwards.

Publisher:Spiegel & Grau, 357 pages.

©2025 The Minnesota Star Tribune. Visit at startribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments