Ken Burns' new documentary begins with Ben Franklin and has Philadelphia at its center

Published in Entertainment News

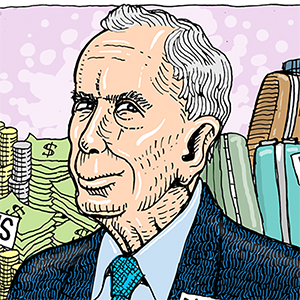

PHILADELPHIA — After capturing hundreds of hours of footage, over a decade, for his new docuseries "The American Revolution," filmmaker Ken Burns knew the epic story had to begin with Benjamin Franklin.

Burns was deeply familiar with the Founding Father from his 2022 PBS documentary, Benjamin Franklin, which helped inform aspects of his latest project, especially the introduction.

Burns and his codirectors Sarah Botstein and David Schmidt wanted to follow the foundational ideas behind the American Revolution — so they started with one of the oldest democracies in the world: the Haudenosaunee Confederacy.

The governing body composed of six Indigenous nations, based mostly in what’s now upstate New York, served as major inspiration for Franklin, who pitched it as a model for the emerging American union some 20 years before the Declaration of Independence.

“Benjamin Franklin [developed a] fascination with the Iroquois Confederacy, the Haudenosaunee, as it was called … that had been working as a functioning democracy for centuries,” said Burns, who has dedicated his career to chronicling American history. “He thought, ‘Oh, maybe we can do that, too.’”

That’s where Burns, Botstein, and Schmidt begin their six-part, twelve-hour documentary that will premiere on PBS on Nov. 16, just ahead of the Semiquincentennial celebration in 2026.

It spotlights all the key figures, from Franklin to George Washington to John Adams, along with celebrity voice-overs like Mandy Patinkin reprising his Franklin and Paul Giamatti speaking as Adams (a nod to his legendary turn in HBO’s 2008 miniseries, "John Adams").

“The folks that we associate with [the American Revolution], they’ve become so two dimensional that our first job is to sort of make them real and dimensional human beings, and then introduce literally dozens, if not scores, of other people who are engaged, particularly women, who are at the heart of the story,” said Burns.

The film widens the scope beyond the major battles, political events, and societal movements to encompass the perspectives of groups long overlooked in history books, from free and enslaved African Americans, to Native Americans, to women of all ages. That includes the story of James Forten, a Black Founding Father who fought in the Revolutionary War.

“James Forten was nine years old, a free Black boy in Philadelphia who hears the first time the Declaration is read aloud, and he doesn’t for a second and believe that these ‘self-evident truths’ didn’t apply to him,” said Burns.

The director hopes that these stories can more comprehensively and honestly portray the reality of this history, about which scholars are still uncovering new information.

At a time when President Donald Trump has targeted exhibits about slavery at Independence Hall for review and potential removal, Burns’ film reminds the nation to look to historians for answers, not politicians. The Semiquincentennial will bring about many reflections on the American Revolution and Burns encourages everyone to challenge their preconceptions — because this history is far from settled.

“It’s really bloody, and it’s not fun, and it’s very complicated to tell, but [this story is] so much better than the kind of bug-in-amber that we’ve made our Revolution, [as] just a bunch of guys in Philadelphia thinking great thoughts,” he said.

Of course, Philadelphia remains at the center of the film as the site where ideas about democracy and independence were first articulated. To portray the city in this historical context, Burns and his team visited Philadelphia dozens of times at various hours of the day, in all sorts of weather, to capture “live cinematography” that gives viewers a sense of that time period, despite being filmed recently.

“We didn’t film a lot in the city of New York because the historic buildings that exist are so overwhelmed by modernity that it doesn’t really work the same way you can get around and film in Philadelphia,” said Botstein, a longtime collaborator of Burns’ who worked on "The U.S. and the Holocaust" and "The Vietnam War." “Figuring out how to shoot that live cinematography, along with all the reenactments and reenactors, and how we visualized the battles — that took us years and years and years of experimenting.”

Obviously no archival footage exists of these historical events, so the filmmakers use the Philadelphia footage to evoke that era, along with close-ups of paintings, drawings, maps, and other historical and archival materials from nearly 350 museums, libraries, and archives around the world.

Burns typically doesn’t incorporate historical reenactments in his films, but he admitted that, in this case, “we had to get over that and over ourselves pretty early” to tell this particular part of American history through what he calls intimate and impressionistic portrayals.

While we all generally know how the story ends, Burns and Botstein relish in the chance to immerse audiences in a narrative that is still surprising about a revolution that was, at the time, considered a major gamble.

They end the series with a quote from another legendary Philadelphian, Benjamin Rush: “The American war is over: but this is far from being the case with the American Revolution.”

“That allows the ideas to be active and not passive, to be alive and not dormant, to be ever-changing,” said Burns. “It’s a process phrase. This is at the heart of us. So, yeah, we just told the story in 12 hours of the American Revolution, but it’s an ongoing idea.”

©2025 The Philadelphia Inquirer, LLC. Visit at inquirer.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments