Column: Chevy Chase and Seymour Hersh get the documentaries they deserve

Published in Entertainment News

CHICAGO — Be thankful that you are not Cornelius Crane “Chevy” Chase.

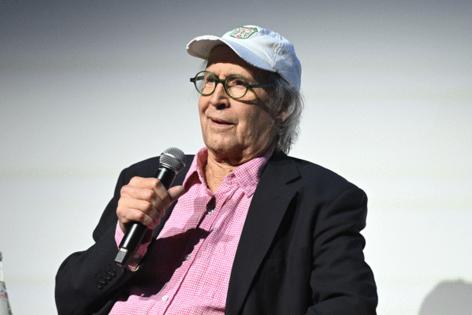

The subject of a new CNN documentary titled “I’m Chevy Chase and You’re Not” is not a particularly pleasant person, even though some of his churlishness may have been caused by a brutal and physically abusive childhood.

Now 82 years old, Chase comes off as a surly, forgetful man. But the comedian is one of two fascinating, if vastly different people currently being examined in documentary form. The other is Seymour Hersh, an investigative reporter/writer of the shoe-leather era, a throwback who is still at the admirable if frustrating business, fighting the good fight in an increasingly muddy media landscape.

Neither man seems particularly anxious for these on-camera ventures, both uneasy with self-reflection, but that reluctance adds a certain intimacy to both programs.

Though a generation may not know his name, Chase was a big star for a time, launching during the first 1975 season of “Saturday Night Live” on the fuel of his pratfalls imitating President Gerald Ford and his tiresomely smug delivery of “Weekend Update.”

After one year, he was lured to big screens, starring in such 1980s financial hits as “Caddyshack,” “Fletch,” the “National Lampoon’s Vacation” movies and “Three Amigos.” He hosted the Academy Awards, twice. And then, as the movie roles became increasingly forgettable — anyone remember “Nothing But Trouble,” “Memoirs of an Invisible Man,” “Cops & Robbersons”? — he tried to capitalize his waning renown by tackling television.

I was the Tribune's TV critic in 1993 when “The Chevy Chase Show” premiered as a late-night offering on Fox. Reviewing it, I wrote that he was “a study in self-obsession and nervous almost beyond belief.”

I wrote that the show was “painfully awkward and lame,” that he was filled with nervous tics” and that viewers could “discover how out of whack it all was … (by watching) the show’s ‘News Update,’ the satirical newscast segment that was the seed of Chase’s ‘SNL’ popularity and something that was expected to be the centerpiece of this show. … Chase’s delivery was unsure and the humor, rather than topical, was sophomoric.”

The show was a bust, and though Chase would make more movies and become a ubiquitous guest on late-night shows, he would never recapture his stardom. Three decades ago, he moved from Hollywood into what appears to be a comfortably luxurious home in quiet Bedford, New York.

His life has been scarred by some cocaine and booze troubles, and serious heart issues. His three daughters and his wife of more than four decades have loving things to say about him, as do Dan Aykroyd, Goldie Hawn and Martin Short. But it is Chase who dominates the 97-minute-long film directed by Marina Zenovich, who has previously made films about such difficult characters as Richard Pryor and Roman Polanski.

She touches sensitively on a couple of potentially incendiary subjects involving a homophobic slur and the use of a racial slur when Chase was a cast member for a few years on the NBC comedy “Community.” The star refuses to discuss that at length but did express his disappointment at not being asked to be a part of the recent “SNL” 50th anniversary bash.

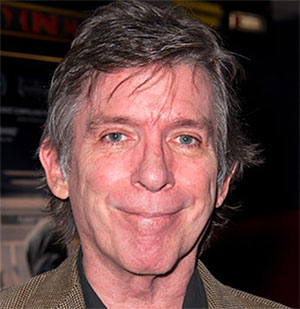

Seymour Hersh is not an easy subject either, but at least he is a gentleman and not resting on his considerable accomplishments.

He fell in love with journalism here. The son of Russian immigrants, he attended Hyde Park High School while working in his father’s laundry and dry cleaning business.

While a student at the University of Illinois’ Chicago campus, then housed in Navy Pier, he impressed a teacher with his writing. He thought Hersh would make a good newspaperman, told him so, and helped him get into the University of Chicago. That professor was, I’m proud to tell you, my uncle Bernard Kogan, not mentioned by name in the program but acknowledged often over the years by Hersh.

At the University of Chicago, Hersh learned about and was steered to the City News Bureau, the bygone training ground for such journalists as Mike Royko and my father, Herman Kogan. He started in the mailroom but was soon hitting the streets, where, he says in the film, he “fell in love with being a reporter,” especially covering the colorful worlds of organized crime and the police. (He also fell in love with his future wife, psychologist Elizabeth Klein. Though she is not interviewed in the program, they have three adult children, are still together, and he says of her, “I married the right person who can calm me down and keep me from going into total despair because I was writing such terrible stuff.”)

Indeed, and there was nothing worse than one of his first investigations.

In 1969, he was working for the Dispatch News Service when he investigated and wrote about what would be known as the My Lai massacre, detailing how the U.S. Army attempted to cover up an incident of troops killing hundreds of Vietnamese civilians. One of the most chilling lines was what the Indiana mother of one of the soldiers told Hersh: “I sent them a good boy, and they made him a murderer.”

The story added fuel to the anti-war movement, and it won the 1970 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting.

The two-hour-long film, “Cover-Up,” directed by Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus, gives us so much more, cutting effectively through the understandable glare of Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman as reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein in “All the President’s Men,” which made it easy to forget what a crucial role Hersh’s work played in that story.

We also see how Hersh got the story of the CIA’s role in spying on student groups, and the torture and abuse of prisoners at Abu Ghraib during the U.S. war on terror. And there was a steady stream of investigations; his work appeared in many places, including the Associated Press, The New York Times, The New Yorker and Substack. He has written 11 books.

He sits in “Cover-Up” still determined to find the truth in this world of “fake news.” Surrounded by piles of files and notes, Hersh is forthright. He owns up to his mistakes, one of which involved being fooled by fake documents that he had to cut from his 1997 book about President John F. Kennedy, “The Dark Side of Camelot.”

Surrounded by piles of files and notes, Sy Hersh is the real deal. He is not merely a survivor in today’s modern media mess. He’s a hero.

———

(Rick Kogan is a columnist for the Chicago Tribune.)

———

©2026 Chicago Tribune. Visit chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments