Q&A: 'Stereophonic' arrives in Chicago, telling the story of a band through its songs

Published in Entertainment News

CHICAGO — Playwright David Adjmi’s “Stereophonic” was one of the big hits of the 2024-25 Broadway season, “a three-hour dissection of ego, insecurity and the messy, messed-up gorgeousness of the creative process,” I wrote then in my review. Adjmi’s play, about a famous but fraught British band a bit like Fleetwood Mac making a studio album in California between the summers of 1976 and 1977, is now on its first national tour.

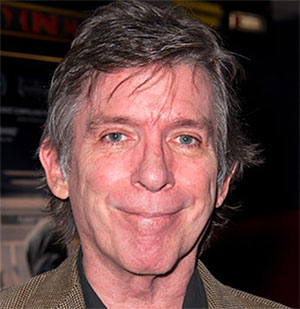

The show comes complete with original music by Will Butler, a former member of the rock band Arcade Fire, and begins performances Wednesday at the CIBC Theatre in Chicago.

Adjmi and Butler spoke about their show over Zoom from London and New York; our conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Q: I hear the script is a little different for the tour?

Adjmi: One of the conditions of doing the tour was that I had to shorten it a little bit. Officially, it’s called the “Radio Edit.” That’s the name I came up with for the draft. It’s about 15 minutes shorter than what people saw on Broadway, so it’s not exactly the same text, but I am proud of the draft. It preserves the spirit and integrity of the piece.

Q: It is hard for me to imagine anyone else performing this show other than the original cast. But you’ve had a successful London production, and there no doubt are many people who can perform the show.

Adjmi: It’s a very hard show to cast. We took six or seven months to cast the show originally. It requires a very specific skill set. In many cases, we had to find people who could play these instruments and also act it. Eight times. In terms of what it asks from the actors, it is in the range of a John Cassavetes movie. London also was a brutal casting process, but in the end, we found the actors. But it’s not the kind of play anyone can be in.

Butler: The play is robust and it supports many interpretations. It has been delightful to see the show in Seattle in a giant house and also in a tiny house in London. You experience it differently in different houses. In some theaters, it seems cinematic and it others, grimy. The play stands up to both.

Q: I wrote when I first saw the show that it was about artistic collaboration and why collaborations have to end. Or why anything ends, really.

Adjmi: I wrote the play because I had had a very bad collaboration in the theater that was existential for me. It made me question if I could make things with people, or if my plays were too specific or that they didn’t invite the collaborative intimacy that some people asked for. I was also confused about relationships. Personal relationships. Familial relationships. So I think I wrote this play as a way of putting myself into a very uncomfortable situation, by proxy of the characters, to see how I could survive this weird half-life of relationships that don’t quite end but can’t really endure. I learned something I already knew, but that I hadn’t fully fully expressed to myself: Life is about duality, art is about duality and part of being a mature human being is about accepting that duality and learning to accept it.

Q: One of the band members becomes dictatorial. He messes up the collaboration by telling people what to do, no?

Adjmi: But he also has a vision. So the show explores the tension between, how do you pursue a vision and maybe it feels bad to some people that this one vision is dominating, but then the product ends up being incredible and everyone benefits from it? To me, that is very interesting. How do you operate as a collective when you have a mix of process and needs? We had that issue making the show,. Luckily, Daniel Aukin is a very collaborative director. And I think what Will and I did together was pretty deep in the end.

Butler: There are two different worlds of collaboration. One where you are trying to do a thing and people have a skill set and you put the thing together. But if you are doing something new, you are trying to get everyone to exceed their abilities, your own self included. You’re trying to go farther than what you know how to do. That’s really hard and exhausting. It’s the difference between going for a work-out run and running a race. … In the process of making this show, we were all trying to be a bit beyond what our abilities were and pull that out from other people. You do need someone to draw people out, to push. But if it’s a total wilderness …

Q: The songs in the show are meta, right? They are songs in a play with music. They are songs with a real-life referent and they are songs that are entirely fictional. They don’t function in the way that songs in a musical function, but also not in the way that songs written for an album function. So what really are these songs?

Butler: Everyone was done in the service of the play — what makes the characters more real, what makes the world of the play work. We all wanted the play to shine. Some of that was very granular work — changing a word here or making the perfect melody that will work for the same 20 seconds, three or four times. Some of it was more traditional songwriting: “Let’s write a song or try this song in this slot.” So there were three or four different modes. Write a song, write this one little crack in the world. The music does function as music usually does in a musical, in that it cracks the world open for a minute and then it seals back up again.

Q: Did you write other songs that got discarded in the, ahem, collaborative process?

Butler: There was a decent pile of things that were not used. But what we had in the end was pretty tight, pretty self-referential, even when it’s not explained. For my own sake, all of those threads had to be tied together.

Q: But what about your compositional mindset, beyond serving the play? What did this play lead you to compositionally?

Butler: I knew there were three singers and I knew they would be singing in three-part harmony. And three-part harmony sounds so 1976. It sounds like the Eagles, post-Credence, post-Buffalo Springfield. One male and two female voices. I didn’t really appreciate it compositionally until we set it on the actors and we saw how much character work that harmony was doing.

When they sing together really tight, you know why these people are in this room together. You know they are meant to be.

———

Through Feb. 8 at the CIBC Theatre, 18 W. Monroe St.; www.broadwayinchicago.com.

———

©2026 Chicago Tribune. Visit chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments