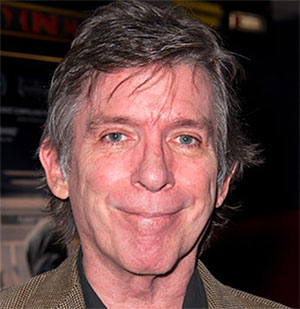

Monkees' Micky Dolenz celebrates his late bandmates on 60th anniversary tour

Published in Entertainment News

ANAHEIM, Calif. — Micky Dolenz is the last of the Monkees — Michael Nesmith, Peter Tork and Davy Jones all are gone — but when he steps on stage to perform, he says he’s never really alone.

“It’s weird. In a way, they’re still here,” Dolenz says on a recent call to talk about 60 Years of the Monkees, his new tour for 2026. “Because every show I do, I show video. Every show I do, I sing songs that Mike wrote or even sang.

“I think about it all the time,” he says. “After Davy passed, I couldn’t even look at some of the video behind me without tearing up. It was tough.”

Nesmith was the last to go. He died in December 2021, less than a month after he and Dolenz wrapped up the Monkees Farewell Tour with a show at the Greek Theatre in Los Angeles. Tork died in 2019, Jones in 2012.

And that might have been that, but for Dolenz’s love and care for the Monkees’ legacy.

“I do feel a responsibility, I guess, to kind of keep the home fires burning,” he says.

This new tour celebrates the 60th anniversary of “The Monkees” TV sitcom, which premiered in September 1966.

“I will be speaking to that,” Dolenz says. “But frankly, it’s always 90% the music. We intend to do the hit songs, the fan favorites from each album, chronologically.

“But also weaving in the origin of the show, the history, the casting process. And I always speak volumes about the songwriters, because as you probably know, we had some of the best ever writing for us.”

Does that mean “Last Train to Clarksville,” the Monkees’ debut single and first No. 1 hit, opens the show?

“Yep, you nailed it,” Dolenz says. “But I’ve started many shows with that because it’s just a great opener and the first big hit off the first album.

“The rest of the set we haven’t locked down, except that albums will be in order,” he says. “Our problem, now my problem, is what not to do.

“There’s always the can’t-not-do’s like ‘Clarksville,’ like ‘I’m a Believer,’ like ‘Pleasant Valley Sunday,’ like ‘Stepping Stone,’” Dolenz continues. “Then it’s always a challenge and fun to kind of go, ‘Well, how about this one we haven’t done for a while?’”

Getting the gig

Dolenz had starred in two seasons of the TV series “Circus Boy” as a child actor in the late ’50s, but was in college studying architecture when he auditioned for “The Monkees” in 1965.

“I thought if I couldn’t make it as an architect, I could always fall back on showbiz,” he says. “That was my parents’ business. During the summers, ’63, ’64, I was doing day jobs on TV shows at the time. “Mr. Novak, “Peyton Place,” during school breaks.

“Then pilot season would come along, and I would go up for some pilots,” Dolenz says. “That year, ’65, pilot season came along, and there were at least two or three other shows that were music-oriented aimed at the younger generation.”

The rise of bands such as the Beatles and the Beach Boys, and the general popularity of rock, pop and folk music had caught the attention of executives in the studios and production companies, and all of them wanted their own piece of the youth market.

“Obviously, they want to make a show the kids will like,” Dolenz says. “In fact, most of the auditions I went to were these other musical shows.

“There was one that was like a Beach Boys surfing band,” he says. “There was one that was like a Peter, Paul, and Mary folk group. There was one like a New Christy Minstrels, a big family, ‘Mighty Wind’ folk thing.

“And then there was ‘The Monkees,” he says. “You’ve heard about the ad in the trade newspapers?” [Variety and the Hollywood Reporter ran ads for open auditions for hip young men.] Well, I’d already had a series as a kid, so I had an agent. I didn’t go to a cattle call.

“When one has had one’s own series, one has a private audition,” he says in his best pompous thespian voice.

“When I went into the audition, there were these two guys sitting there in jeans and T-shirts, eating pizza,” Dolenz says. “I thought they were there for the audition. They were the producers, the creators, Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider. So from the get-go, it was different.”

Rafelson and Schneider weren’t that much older than Dolenz, and they were into the same kind of things he and his future castmates in the series liked.

“They were out of the East Coast, Kerouac, beatnik, Greenwich Village scene,” he says. “They were huge fans of the Beatles.” I remember thinking at the time, ‘Oh boy, this is different. I really would like to get this one.’”

He auditioned with Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode,” accompanying himself on guitar. He did scene studies, improv, and a filmed screen test, none of which were common for TV series at the time.

“So they cast me, and they said, ‘You’re going to be the drummer,’” Dolenz says. “I said, ‘Well, I play guitar.’ They said, ‘We know, but we got lots of guitar players.’ So I said, ‘Fine, where do I start?’”

‘Where do I start?’

That willingness to do what was required for the job was a product of his past work in film and television, as well as growing up with parents who were actors and singers themselves, Dolenz says.

“When I had been cast in ‘”Circus Boy”‘ in the ’50s, they said, ‘You’re going to learn to ride an elephant,’” he says. “I said, ‘Great, where do I start?’ If somebody had said, ‘You’re going to be a scuba diver,’ I would have said, ‘Yeah, where do I start?’”

If Rafelson and Schneider wanted him to play the drums in addition to being the Monkees’ co-lead vocalist with Jones? Not a problem.

Dolenz says he remembers meeting Jones during the audition process, possibly because Jones was also an experienced actor as a child and young man in his native England and on Broadway.

“I do remember the day we met all together,” he says. “It was a wardrobe fitting, because that’s the first thing you do when you do a pilot.

“It was on the same lot, same set, the same place where I did ‘Circus Boy,’” Dolenz says. “Some of the crew on the Monkees were the same crew from ‘Circus Boy’ 10 years earlier, so it was like old-home week for me.

“But I remember quite clearly, on the lot in front of the wardrobe department, one of the producers said, “OK, Micky, this is Mike, Mike this is Peter, Peter this is Davy, you guys are the Monkees,” he says.

Even then, though, the four actor-musicians didn’t really start to bond yet.

“When we met, I hadn’t even quit school,” Dolenz says. “It wasn’t like I knew we were going to spend a lot of time together. The pilot might not have sold. Remember, the Monkees was not a group; it was a musical comedy television show about a group.

“When I got the pilot, it was right in the middle of a semester,” he says. “I just took 10 days off school to do the pilot, and then I went back to school.”

Only when the show was greenlit by NBC with a 26-episode order for its first season did he finally stop his studies. Only then did the chemistry of the casting start to surface as the four Monkees came together on the set.

“The producers of any show are looking for that chemistry, charisma, the click,” Dolenz says. “One of the producers, when asked about the Monkees, said, ‘We just caught lightning in a bottle.’ That’s what happens.”

Chemistry tests

Quickly, in those first few months of the show, the actors gelled into a tight unit that would fix scenes based on their deep understanding of their characters, Dolenz says.

“Within the first couple of episodes, we would be telling the director, ‘Oh, wait a minute, Davy wouldn’t say that line, that’s a Micky line,’” he says. “And they would go for it. They were capitalizing on the improvisational qualities that they had been looking for.”

Musically, though, the guys in the fictional band all had distinctly different backgrounds.

“Music-wise, it was not difficult, but it was different,” Dolenz says. “In the ‘normal’ group, they were brothers and cousins like the Beach Boys, or they met when they were 14 years old like the Beatles. That’s more common, and they tend to be very, very similar in type and style.

“Because there’s usually one singer-songwriter, maybe two, and they’ll surround themselves with like-minded artists who are of the same spirit, the same genre of music,” he says. “That’s what usually happens.

“Well, with the Monkees, you had four lead singers with entirely different genres. Not one better than the other, but very distinct genres.

“Mike Nesmith, country, electric, pop rock,” Dolenz continues. “Me, I was singing rock and roll, screaming Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis. Davy doing Broadway ballads. Peter doing hardcore Greenwich Village folky, bluesy, Woody Guthrie stuff.”

It wasn’t always easy to make their musical backgrounds fit, he says.

“But in a way, I think that becomes one of the really interesting things, those different flavors.”

Singers and songs

The Monkees music came from the cream of contemporary songwriters in the ’60s in that period just before songwriters increasingly began to sing their own work. Neil Diamond, Carole King, Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart, and Jeff Barry all wrote hits for the group.

“When I was cast and the series went into production, I remember the [music] publisher taking me down to a little bunch of offices on Sunset Boulevard,” Dolenz says. “He said you should meet the songwriters who are going to be writing songs for you. This is me, just by myself. And I said great.

“Went down and into this little hallway of cubbyholes,” he says. “He opened the door and this was girl sitting behind the piano with a Wollensak taperecorder, and he said, “Micky Dolenz, Carole King. Carole will be writing songs for you. I’m like, ‘Oh, hi.’

“Remember, I’m 20 years old, she’s like 23. And he walked down the hall and said, ‘Here, Micky, this is David Gates; David, this is Micky Dolenz.”

In those days, no one really knew the names of songwriters for pop hits, Dolenz says. Only later, when King recorded albums such as “Tapestry” and Gates co-founded and sang lead vocals in Bread, would writers like them find individual fame.

For Dolenz, though, the work the songwriters delivered was accepted with the same can-do spirit of his “When do I start?” attitude to most things.

“They would offer me demos, and I’d listen and sing along with it,” he says. “I don’t recall ever — I probably did occasionally — say, ‘I don’t think this is my kind of song.’ And I was quite happy to do that.”

At times, though, his workload as one of the Monkees lead singers took a toll.

“I had to record so much material because they wanted two new songs every television show,” Dolenz says. “And there were 26 episodes a year. So I would go in after filming the TV show 10 or 12 hours a day, and sometimes record two vocals a night.

“A funny side story — you know the song ‘Clarksville’? the bit in the middle?”

He sings the nonverbal runs that appear in its bridge.

“Well, that had words to it originally,” Dolenz continues. “I don’t remember what they were. Something like, ‘Going to the station and I’ll meet you in the morning and I’ll bada bada bada,’” he sings.

“Years later, Tommy Boyce reminded me there were words to that bit,” he says. “I said, ‘Really?’ He said, ‘Yeah, but it was midnight. You had just come off the show for 10 hours.’ And you said, “I can’t do that, I can’t learn all these words and sing that. It’s late, and I’ve got to go home.”

“And he said, ‘Oh [bleep], just go “Doodle doodle doodle do,” ‘ ” Dolenz says and laughs. “And that of course has become a great hook.”

Becoming real

Dolenz has long been annoyed that some have dismissed the Monkees as a manufactured band, as if that made them less legitimate than their performances live and in the studio show them to be.

The problem, he says, is that they’re looking at the show all wrong.

“Just always keep in mind that the Monkees was not a group,” he says. “It was the cast of a musical comedy television show. It was Marx Brothers movies for half an hour on TV. If you can get your head around it, everything makes more sense.”

But then they were sent on tour, so … ?

“I know where you’re going with that, and you’re absolutely right,” Dolenz says. “They must have had it in mind or they wouldn’t have had musicians and singers. They would have done the old Hollywood thing of dubbing Natalie Wood’s voice [in “West Side Story”] or Steve Allen as Benny Goodman [in “The Benny Goodman Story”].

“Nobody ever talks about that or says, ‘Oh, you know he wasn’t playing,’” he says. “But the Monkees was different from the get-go. The producers must have had that in mind, that if the show even gets on the air, we’re going to do it and do it for real.”

Forty years later, the TV series “Glee” did something similar, Dolenz notes.

“Those were kids who could do it all,” he says. “They were an imaginary glee club, but they went out on the road [to do live shows] because they could all sing and dance and act. This is 40 years after the Monkees. You wouldn’t have called that a manufactured glee club, would you?”

When Dolenz, Jones, Nesmith and Tork eventually did gain more control over their work in the studio and their live performances on the road, that marked the chapter Dolenz describes as Monkees 2.0, which lasts through various reunions to today.

“I think Mike Nesmith came up with the perfect description,” Dolenz says. “He said, ‘When we went on the road and hit that stage the first time in front of thousands of kids, Pinocchio became a real boy.’”

©2026 MediaNews Group, Inc. Visit ocregister.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments