Mary McNamara: 'Love Story' is guilty of the same invasion of JFK Jr. and Carolyn Bessette's lives that it condemns

Published in Entertainment News

Will film and television never tire of riffling through the bones of dead Kennedys? Not this year, apparently.

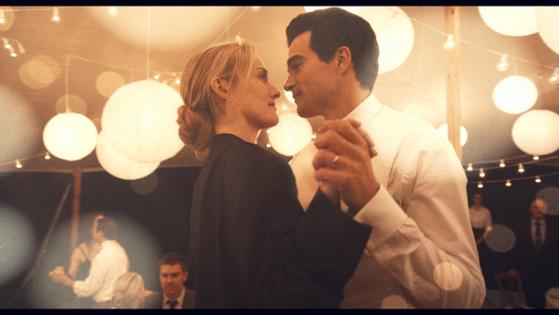

Adding to the already Homeric list of fictionalized depictions of a family so mythically weighted with tragedy that many consider it cursed comes FX’s “Love Story: John F. Kennedy Jr. & Carolyn Bessette,” which chronicles the couple’s high-profile courtship, marriage and, of course, shocking and untimely end.

Framed as an American version of the Princess Di story — winsome young woman falls for the son of a judgmental and unwelcoming power family only to be endlessly stalked by a voracious and predatory media as their romance unravels — “Love Story” starts off as a glamorous, tantalizing modern fairy tale before devolving into a rather heavy-handed analysis of familial expectation and the perils of fame.

It includes having your most intimate moments fictionalized for the purposes of a miniseries and, in Kennedy’s case, your father’s assassination and your family’s reaction to trauma raked over one more time.

But hey, that’s entertainment.

From the moment of his birth, mere weeks after his father was elected president, the son of John F. Kennedy and Jacqueline Kennedy was a national fixation. As he grew into a handsome, charming and ambitious young man, he was endlessly dogged by photographers. And while his sister Caroline rigorously guarded her privacy, John chose a public life. Famously dubbed People magazine’s Sexiest Man Alive in 1988, he lived in New York City where he was often seen biking to his job, first in the Manhattan D.A.’s office and later at the offices of George, the political/pop culture magazine he founded. A coveted and perennial party guest, he was considered the country’s most eligible bachelor — who can forget his role as Elaine’s object of sexual fantasy in the 1992 “Seinfeld” episode “The Contest”?

When he began dating, and then married Carolyn Bessette, a director of publicity for Calvin Klein, media attention exploded. If Kennedy was an American prince, the lovely and stylish Bessette was his princess, loved, hated and swarmed at every turn by a predatory paparazzi. Tabloids and magazines regularly reported on the state of the relationship, often unkindly. When the couple was killed, along with Bessette’s older sister, Lauren, in a private plane piloted by Kennedy that crashed in July 1999 as the couple was on its way to attend Rory Kennedy’s Hyannis Port wedding, the nation reeled in shock and mourning.

That much is fact. The rest, including “Love Story,” created by Connor Hines and executive produced by Ryan Murphy, is fictionalized storytelling. Murphy has built a multiverse on his fascination with the kind of tragedies, feuds and horrors that dominate headlines; the Kennedy-Bessette story is right up his alley, exploring a slightly more contemporary version of the New York elite milieu (down to Jackie Kennedy’s sister Lee Radziwill) of “Feud: Capote vs. the Swans,” another of his series.

High-profile love that ends in tragic death is, of course, a bedrock of storytelling, but this “Love Story” purports to have a higher calling. Loosely based on Elizabeth Beller’s biography “Once Upon a Time: The Captivating Life of Carolyn Bessette-Kennedy,” per those involved, it is an act of historical correction, an attempt to push back against a narrative in which Bessette was a cold, calculating (albeit very stylish) manipulator responsible for Kennedy’s unhappiness and, quite possibly, the plane crash that killed them more than a quarter century ago.

At this point, I don’t know how firmly entrenched such a narrative remains, given that it was fairly New York-centric to begin with; most people under the age of 50 probably don’t remember all that much about the couple beyond their combined and separate beauty and the tragedy of their deaths. But those who knew and loved Bessette may find comfort here.

In this telling, Bessette (Sarah Pidgeon) is an ambitious but kind and free-spirited young woman who, by dint of great personal style and excellent customer sense, leapfrogged from sweater-folding mall retail to the headquarters of Calvin Klein. There she catches the attention of the maestro himself (Alessandro Nivola) by suggesting that Annette Bening wear a man’s suit jacket to the “Bugsy” premiere (which Bening did). Klein is so impressed that he scoops her up at one of the company’s fancy events and presents her to Kennedy (Paul Anthony Kelly) — “You’re going to thank me for this,” Klein tells her.

Far from swooning as she is clearly expected to do, Bessette banters tartly and refuses to give him her number. “You know where I work,” she says. “Try reception.”

It’s a terrific moment, and Pidgeon sells it, just as she sells Bessette’s initial inner conflict — she knows that getting involved with the American prince is a bad idea, but he is very persistent and, well, she just can’t help herself.

We’ll have to take her word for that. Kelly was clearly cast for his physical resemblance to Kennedy, but try as he might he never captures JFK Jr.’s natural charisma or sex appeal. For all of Pidgeon’s best efforts, it’s difficult to believe that passionate love is what overcomes Bessette’s very legitimate aversion to being trapped in the orbit of a famous man rather than entering a romantic partnership with him.

Which, according to Jacqueline (Naomi Watts), is precisely what any woman her son marries will have to accept, as she knows only too well. This is why Jackie has disapproved of all his romantic partners, including and especially his on-again, off-again girlfriend Daryl Hannah (Dree Hemingway). Jackie’s disdain for her makes a certain amount of sense given the whiny, entitled and oblivious manner in which Hannah is written here — you honestly can’t imagine why she and Kennedy are ever on-again — but it’s an excuse for Jackie and Caroline (Grace Gummer) to exude irritation with Kennedy and deliver all manner of lectures on how he needs to get his act together.

By turns hangdog and defiant, this version of JFK Jr. is a little boy lost, positioned as a victim of his name and his mother’s expectations — on top of the unsuitable girlfriends, she doesn’t think much of his decision to leave law and start a magazine.

The former first lady’s influence over her son offers, regrettably, an excuse to rummage around in her own life, particularly (and in at least one scene, unforgivably) her final days. Watts, working through an eternal haze of cigarette smoke, gives as fine a performance as the nagging-mother material allows. But Hines cannot resist repeatedly dragging Jackie back to Camelot and that fateful day in Dallas.

Gummer’s Caroline is intelligent, witty and acerbic — when John complains that Jackie doesn’t judge her as harshly as she does him, Caroline retorts that her many psychiatrists would disagree — but she too is set up almost entirely as an obstacle to the love story. With Bessette as the clear hero of this tale, it is impossible not to see Caroline, even with the humor and humanity Gummer brings, as an antagonist, rude when she need not be and dismissive of the choices her brother has made.

New York in the mid-to-late ‘90s plays something of a role here — the tabloid headlines when John flunks the bar exam, the Mark Wahlberg (then Marky Mark) scandal, the rise of Kate Moss, the struggles of Kennedy’s magazine George — but many of the “street scenes” appear cleared for filming, except when they are filled with paparazzi.

In early episodes, the Kleins, Calvin and Kelly (Leila George), offer a thematic and at times far more tantalizing counterpoint; Kelly knows what it’s like to play second banana to a famous man (they would separate the same year Kennedy and Bessette married). As the domineering yet insecure designer (who did not come out as bisexual until 2006), Nivola is a bright spot of the series; his Klein has far more chemistry, albeit of the non-romantic type, with Bessette than John does.

Still, there is pleasure to be had in watching these initially star-crossed lovers dodge all the lectures and prophecies of doom — the always excellent Constance Zimmer shows up as Bessette’s mother, who is not happy about the match either — as they make their way to each other.

But as the series progresses (eight of nine episodes were made available), the media’s appetite for images of and rumors about the couple make Bessette’s life increasingly confined and unhappy. The energy of the series flags considerably and it’s difficult not to feel a little queasy as we watch her unravel.

It’s always difficult to make a series or film that explores the pressures of fame and media-fed public interest without seeming hypocritical. In “Love Story,” the real villain is the public’s unceasing demand for access to the lives of John F. Kennedy Jr. and Carolyn Bessette, whether they want to grant it or not.

There is no escaping the fact that by watching “Love Story,” we are engaging in a posthumous version of the very same thing.

———

(Mary McNamara is a culture columnist and critic for the Los Angeles Times.)

———

©2026 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments