Does your deed say Black, Jewish, or Polish people can't live in your home? In Pa., there's a new way to address old discriminatory language

Published in Home and Consumer News

In 1927, 44 homeowners living on West Penn Street in Germantown, Pennsylvania, got together to write a rule for who could and couldn’t buy or rent their properties. They excluded everyone “other than those of the Caucasian race.”

And then they went even further.

If anyone of any other race occupied any of the properties, the covenant read, neighbors could evict them “by force of arms.”

“You can go in with guns blazing to remove people who aren’t supposed to be there in your view,” said Marshal Granor, a real estate attorney in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. “Wow.”

Despite references to “forever,” restrictive racial covenants such as this one are no longer allowed or enforceable, thanks to federal law and state protections. But in the deeds of properties across the region and the country, they still exist. And many homebuyers and owners are horrified when they find this kind of racist language in their own properties’ documents.

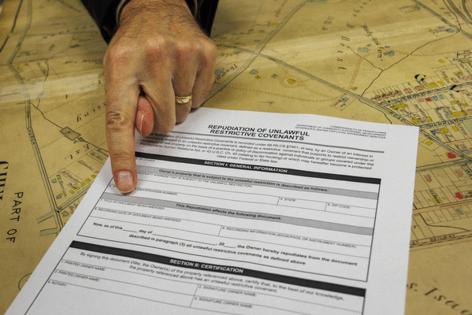

To address these historical restrictions, Pennsylvania passed a law in December that allows property owners to file a one-page form that gets attached to the deed and disavows and nullifies discriminatory language in it. The free form is submitted to the local county’s Recorder of Deeds office.

Pennsylvania joined states throughout the country, including New Jersey and Delaware, that have passed laws to address discriminatory language in deeds, either by allowing or requiring property owners to file documents to renounce it or by removing it.

Restrictive racial covenants thrived in the 1920s, when exclusionary zoning began to spread throughout the country and developers wrote restrictions into new deeds as a common business practice. As late as the 1950s, “Levittown” planned communities that were built in Bucks and Burlington Counties, Pennsylvania, included racial restrictive covenants. These covenants aren’t common in the Philadelphia region, and there’s been no run on Recorder of Deeds offices since the new form became available six months ago. As of early October, no property owner in the five-county area had filed a form.

But Granor, the attorney behind the push for the law, has been trying to spread the word, talking to groups of attorneys and real estate professionals across Pennsylvania and sometimes moving people to tears.

“The legislature understood that while there may not be a huge line of people lining up to record these repudiations, that it’s important,” said Granor, who is Jewish — one of the identities targeted with restrictive covenants.

“You do have the people who say, you know, it’s not really important because you’re not changing anything,” he said. But the law allows property owners to void the discriminatory language from the time it was first recorded. “We’re taking its power away. And that, to me, is worthwhile.”

What are restrictive covenants?

Restrictive covenants or deed restrictions are private limitations on how property can be used that stay with the property from owner to owner. They can ban certain activities and structures — outhouses, for example — and historically have been used to ban certain people.

A century ago, homeowners and developers could be as broad or specific as they wanted to be in deciding who to keep out. People who were Black, Jewish, Polish, Italian, Austrian, Russian, Hungarian or “foreigners” were among those listed in deed restrictions as forbidden from owning or occupying properties in Pennsylvania communities.

In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court reaffirmed that racial deed restrictions were legal but said state governments could not enforce them. The Fair Housing Act of 1968 made discrimination in the sale and rental of properties illegal.

Searching large numbers of documents for restrictive covenants became possible with the digitization of property records. That enabled researchers to publish reports that showed just how common these restrictions were throughout the country.

In the first comprehensive analysis of Philadelphia deeds published in 2019, the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia found that between 1920 and 1932, the deeds of almost 4,000 properties in the city included language that banned people of certain races. The report included the example of the Germantown homeowners on West Penn Street.

“In response to a number of projects around the country, there became an interest in addressing these remnants of nasty racial discrimination,” said Colin Gordon, a history professor at the University of Iowa and author of Patchwork Apartheid: Private Restriction, Racial Segregation, and Urban Inequality.

Last century, real estate agents were among the professionals who supported restrictive covenants, because they considered them useful to make places more desirable to white buyers and important for maintaining property values. The predecessor to the National Association of Realtors, partnering with the U.S. Department of Commerce, created a model racial covenant in 1927 that it encouraged agents to use.

Now, Pennsylvania’s new law has the support of the Pennsylvania Association of Realtors. Glenn Yoder, chair of the association’s legislative committee, said a commitment to fair housing practices is part of the organization’s code of ethics.

Members have encountered restrictive deed covenants during the course of their work, he said. “And they’ve had clients, both buyers and sellers, say, ‘Why is this on here? This is really ridiculous that it’s on here.’ And it’s very hurtful to a lot of people.”

A member of the Bucks County Association of Realtors called Granor after he’d finished a presentation about Pennsylvania’s then brand-new restrictive covenant law. They said that the day before, “we had a settlement, and the people are sitting there reading their title search and up comes this ‘No Blacks, No Italians, No Jews.’ And what do you do with that?”

Granor replied that an official form was coming. He said real estate brokers, title companies, and other professionals involved in real estate transactions are the law’s “line of offense” and can educate buyers and sellers.

Jeanne Sorg, Montgomery County’s recorder of deeds, said most of the property restrictions she sees relate to things such as where someone can put a chicken coop or cesspool. She doesn’t run into a lot of restrictions based on race, religion, or national origin, she said, “but they are out there.”

“As one of my staff said, you see those and it just makes you sick,” she said.

One deed restriction prohibiting anyone who was not Caucasian was dated as recently as 1946, which “was very surprising to us,” Sorg said. “We’re talking 78 years. That’s not that long ago.”

The Pennsylvania law

Pennsylvania’s restrictive covenant law came to be after several years and iterations.

The law includes two exceptions that were sticking points among some lawmakers. It does not apply to age-based restrictions used to create senior living communities or to deed restrictions used by religious organizations to prevent “the use of the property for purposes that would offend” the organization.

During a presentation to the Dauphin County Bar Association, the legislation’s prime sponsor, State Rep. Justin Fleming, D-Dauphin, said a friend who bought a home in Camp Hill in the 2010s was “horrified” to find that the property’s deed included a discriminatory restriction.

“It was just a reminder that even 60, 70 years after, or even 80 or 90 years after some of these deeds were maybe initially put in, that they still persist to this day,” even though they are unlawful, Fleming said.

New Jersey’s and other states’ solution to restrictive covenants

In November 2021, New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy signed into law legislation that dealt with discriminatory restrictive covenants. If a property owner with these covenants in their deed needs to complete a transaction involving that deed, such as the transfer of the property, they must first file an addendum to the deed that rejects those unenforceable restrictions.

The law also requires the governing boards of groups such as homeowners’ and condo associations to remove restrictive covenants from their governing documents.

New Jersey lawmakers modeled their legislation off a law in Virginia. New Jersey’s law states that “allowing this type of language to continue to be contained in a legal document recorded by a governmental entity of the State of New Jersey ... is a reminder of a hurtful and shameful national legacy that has been outlawed” by federal and state lawmakers.

“I’m proud to say that our 2021 legislation was among the nation’s first to ensure that this hateful legacy can be rectified from our state’s land deeds,” New Jersey State Sen. Troy Singleton, D-Burlington, said in a statement.

Maryland, California, Connecticut, Indiana, Texas, and Washington are among states with laws addressing racial covenants. In 2018, Delaware passed a law that allows property owners to get unlawful restrictive covenants redacted and prohibits a recorder of deeds from recording a document that includes them.

©2024 The Philadelphia Inquirer, LLC. Visit at inquirer.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments