Trump’s Grudge Against South Africa is Based on Racist Fiction

I can hardly think of President Trump and Africa without also remembering his global insult to underdeveloped nations.

In a 2018 Oval Office meeting, you may recall, he grumbled aloud about why this country would accept more immigrants from “shitholes” in Haiti and Africa rather than places like, say, Norway.

With that in mind, I didn’t have a sunny outlook about the prospect of his first meeting last week with South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa. I anticipated an attempt at televised humiliation much like the spectacle Trump sprang on Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelenskyy in February.

The meeting was called ostensibly to smooth strained relations between the two countries, but Trump used it to advance his white genocide agenda.

Trump contends that white South African farmers are being murdered in a racially motivated genocide, and that the South African government has permitted itself to seize their land. He has amplified these false claims since as long ago as 2018, when he seemed to have picked them up from Fox News host Tucker Carlson.

They were the basis of his dismissal earlier this year of South Africa's ambassador to the U.S. — who'd had the temerity to point out the racist overtones of Trump's allegations — and of his executive order to cut off aid to South Africa. He also used them as a justification to grant 59 white South Africans refugee status to the United States while he continues to vilify, arrest and remove immigrants who came here from other countries.

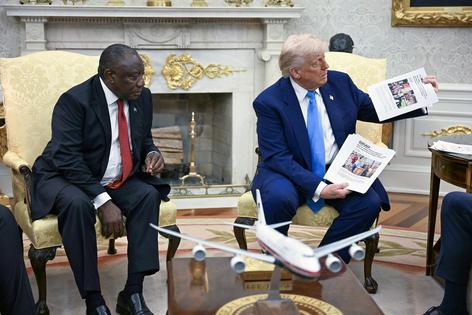

The Oval Office meeting with Ramaphosa had barely begun when Trump ordered the lights dimmed to play purported documentary footage he described, in his special Trumpian way, as like “no one has seen before.”

The video screen offered images that included body bags and graves that Trump claimed contained dead white farmers.

Trump also brandished printed handouts including a blog post purporting to document genocidal atrocities. He flipped through the pages intoning “death ... death.”

“Executed,” Trump said gravely. “These are all White farmers that are being buried.”

“People are fleeing South Africa for their own safety,” Trump said amid a series of accusations. "Their land is being confiscated, and in many cases, they’re being killed."

There is no denying that South Africa has a persistent violent crime problem. Yet, while data available on the country's violent crime indicate that farmers of all racial groups are disturbingly vulnerable to theft and violence, they do not clearly support race as a factor.

Ramaphosa admitted this, pointing out that most of the republic's violent crime victims are Black. In response to the images shown, he said that he would like to find out what the location was.

Trump interrupted, saying: “The farmers are not Black. They happen to be white.”

Ramaphosa responded: “These are concerns we are willing to talk to you about."

It will surprise no one that the grisliest images used in Trump's visual aids were not indeed from South Africa. They were Reuters images from the Democratic Republic of Congo, the news service confirmed. Specifically, they came from the city of Goma, where an insurgency has been raging, and they were published in February.

We know this now, because some institutions in this country still care about the facts, even if our president and his powerful political movement do not.

In the moment of the spectacle, Ramaphosa could hardly refute the images. But he kept his cool.

He had come with a plan. Perhaps most effectively, Ramaphosa allowed others to speak for him. He had brought impressive company. His delegation from South Africa included luxury goods tycoon Johann Rupert and champion golfers Ernie Els and Retief Goosen. Both complimented Ramaphosa’s leadership, perhaps more persuasively, to Trump’s golf-loving heart, than any other South African could have.

Most of South Africa's media appear to be praising Ramaphosa for remaining calm, patient and polite, although some say they wish he had hit back harder.

But Ramaphosa, by reputation, is no pushover. Once a protégé of Nelson Mandela, he was a key negotiator in the talks that ended nearly five decades of racial segregation known as apartheid in 1994.

When I first went to South Africa on assignment in 1976, the summer when riots broke out in Soweto, the Black township outside Johannesburg, little did I know that it would mark the beginning of the last round for apartheid and white-minority rule.

I certainly would not have imagined that a future president of the United States would amplify the racist backlash against the post-apartheid South African state — an entity, it should be said, that stands out in history for its restraint and humanity in addressing and rectifying the shocking, brutal injustices of the racist regime it replaced.

Now the next chapter in South Africa’s history is being written by a new generation with remarkably high hopes. They don’t need outsiders to churn up more racial animosity based on false pretenses. They have enough real problems to tackle — in multiracial coalitions, one hopes.

Meanwhile, our president is solidifying his image as a global leader of white identity politics. He and his movement may deny it, but his message is as clear as a bell.

========

(E-mail Clarence Page at clarence47page@gmail.com.)

©2025 Tribune Content Agency. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

(c) 2025 CLARENCE PAGE DISTRIBUTED BY TRIBUNE MEDIA SERVICES, INC.

Comments