Ronald Brownstein: How to avoid a gerrymandering war

Published in Op Eds

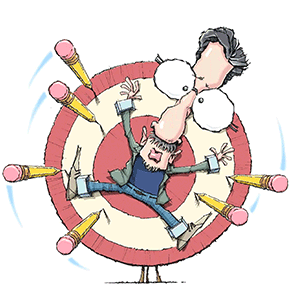

The nakedly partisan congressional redistricting effort that Texas Republicans are pursuing at President Donald Trump’s command shows what the map-making process should not look like. It’s more difficult to say exactly what an appropriate redistricting process should entail.

Reformers typically place the highest priority on avoiding bias toward one party, ensuring that nonwhite voters have a fair chance to elect nonwhite legislators, and maximizing the number of competitive seats. But those priorities can collide. As Michael Waldman, president of the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University Law School, told me, “Redistricting always involves balancing goals.”

Before Trump triggered the current firefight, the Congressional maps that states drew after the 2020 Census appeared to have found a sustainable, if flawed, equilibrium among those central goals. Although civil rights groups have sued several Southern states to create more districts favorable to Black and Hispanic candidates, there have not been widespread complaints about minority disenfranchisement.

On the whole, multiple studies have found that the post-2020 district lines are much less biased toward either party than the Democratic-leaning maps of the late 20th century or the plans that favored Republicans in the early 21st.

“The current House is unusual in the modern era in being very close to perfectly neutral according to various measures of partisan bias,” Nicholas Stephanopoulos, a professor at Harvard Law School and expert in redistricting, told me. Under the current lines, Stephanopoulos and his colleagues have argued, the party that wins the most votes in House elections nationwide is also very likely to win the majority — a big improvement from 2012 when severe gerrymandering allowed Republicans to amass a 33-seat House majority even as Democrats won the national popular vote.

The most conspicuous flaw in the current maps is their lack of competition. Today’s district lines are relatively unbiased not because red and blue states drew fair maps, but mostly because they offset each other in gerrymandering safe seats for their side. States where Republicans controlled the redistricting process, Brennan found, were especially likely to draw uncompetitive seats, but overall just 37 House races were decided by margins of five percentage points or less in the 2024 election compared to 235 that resulted in landslides of 25 points or more.

The geographic sorting of the electorate between blue metros and red-leaning smaller places limits the possible number of competitive seats, but Stephanopoulos told me his ongoing research suggests “that we’d have a lot more competition if line-drawers weren’t trying to make districts safer” for one party.

If Texas succeeds in launching a new redistricting war, it could disrupt the best (if inadvertent) feature of the current maps: their rough partisan balance. In an all-out mobilization, Republicans probably can squeeze out about half a dozen more House seats than Democrats before 2026. That would not shift the maps back all the way to their lopsided pro-GOP tilt after 2010, says Sam Wang, president of the Electoral Innovation Lab at Princeton University. But, he says, it would erase the roughly neutral playing field, and likely force Democrats to win the total House popular vote by 2 to 3 percentage points to claim the majority.

Simultaneously, an all-out war would compound the current maps’ biggest problem. Both red and blue states would likely shrink the paltry number of seats that can realistically flip between the parties. It would become even harder for voters to register discontent with the actions of their legislators. More safe seats would not only reduce accountability but fuel polarization, because members who represent districts that tilt overwhelmingly toward one party are more likely to fear losing in a primary (decided by the most committed activists) than a general election (tipped by swing voters).

The best solution would be legislation establishing comprehensive, national rules for redistricting. In 2021, the Democratic-controlled House passed the sweeping election reform bill known as HR 1 that would have required states to use independent commissions to draw Congressional district lines and applied national standards to that process.

Those included avoiding partisan bias, ensuring geographic continuity in the districts, and barring mid-decade redistricting. (Mid-decade redistricting is exactly what the GOP in Texas is now trying to do; usually seats are redrawn only after the once-a-decade Census.)

The version negotiated by Senate Democrats dropped the requirement for independent commissions but maintained the national standards. Even the Senate bill, Waldman says, “would have stopped what’s going on right now dead in its tracks.” But it died in a Republican filibuster in October 2021 (after then-Democratic Senators Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema refused to lift the filibuster rule to pass it).

There might be other ways to address the gerrymandering problem. Though the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the 2019 Rucho case that federal courts can’t overturn partisan gerrymanders, state legal action may still offer some opportunities to curb excesses: Stephanopoulos and his colleagues at the Harvard Election Law Clinic recently helped craft a novel lawsuit in Wisconsin that argues the extreme lack of competition in the state’s Congressional map “makes a mockery of” the state constitution’s promise of equal protection and the right to vote. In the long run, some election reformers believe that returning to the early 19th-century model of electing multiple members from a single district offers the best chance to ensure both greater fairness and competition.

Still, Congressional legislation establishing nationwide rules (which even the Republican-appointed majority in the Rucho case signaled would pass constitutional muster) remains the most viable way to prevent a redistricting race to the bottom. Republicans have never displayed much interest in such a truce. But the prospect of an unconstrained, years-long confrontation — what Wang calls “a Cuban missile crisis situation of gerrymandering” — might persuade some to reconsider. If not, it’s a safe bet the US will descend further into an upside-down world where officeholders are picking their voters, rather than the other way around.

_____

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Ronald Brownstein is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering politics and policy. He is also a CNN analyst and previously worked for The Atlantic, The National Journal and the Los Angeles Times. He has won multiple professional awards and is the author or editor of seven books.

_____

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments