Mary Ellen Klas: The property tax fight is a power grab in Texas and Florida

Published in Op Eds

As affordability politics take center stage across America, at least 18 states are attempting to lower or eliminate property taxes to offset the dramatic rise in property values. It’s a worthy debate, but wiping out property taxes, or dramatically limiting them, is dangerous.

It not only strips local communities of an economically efficient tax, it also erodes their autonomy, making them more susceptible to any authoritarian-leaning lawmakers at the state level.

There’s little doubt that the conditions for a property tax revolt are ripe. According to the nonpartisan Tax Foundation, property taxes have soared almost 27% faster than inflation since 2020. In just two years, the average sale price of a home in the U.S. rose from $371,100 to $525,100, squeezing out first-time home buyers to a record low of 21% while raising the typical age of first-time buyers to 40, an all-time high.

That’s unsustainable. Over the last year, at least 11 states have taken some kind of action to provide property tax relief, according to the nonpartisan National Conference of State Legislatures. Arkansas expanded its homestead credit. Idaho and Nebraska used state funds to pay for property tax relief. Kansas raised property tax exemptions and several states expanded property tax relief to senior citizens and veterans.

Although many of these reforms keep property taxes down for some homeowners, they also shift the tax burden to new homeowners and new construction, lock existing homeowners into their homes, and exacerbate the larger housing affordability crisis.

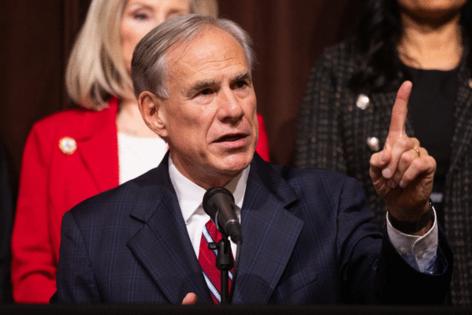

Heading into the midterm elections next year, two of the nation’s largest states are toying with some of these irresponsible policies. Texas Governor Greg Abbott launched his bid for reelection to an unprecedented fourth term on Sunday by unveiling a six-point list of property tax reforms. He wants to slash appraisal growth, wipe out taxes that support public schools, and impose limits on local spending. He offered no plan for how to replace the money cities and counties would lose, but his proposals are sure to get the attention of inflation-weary voters.

Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, who has his eye on a second presidential bid, has mounted an anti-property tax campaign to eliminate levies on homestead property in his state. He portrays property taxes as like having “to pay rent to the government.” He conveniently never talks about how communities use that money to provide essential services — like police, fire, trash collection, parks and recreation, public health and infrastructure.

DeSantis does acknowledge that Florida’s 29 “fiscally constrained” counties will lose an estimated $250 million in revenue, rendering them incapable of providing those services. He downplays the revenue losses as mere “budget dust” but offers as a solution a socialist-like redistribution measure: Counties could come to the state each year and plead for money to restore their lost revenue.

It’s not hard to imagine how this would work. Counties that don’t go along with the governor’s policies on culture-war issues could be punished by having the state withhold the money they need to keep running. It’s not unlikely; both Florida and Texas have already been on a binge to preempt local government laws and don’t take favorably to local communities that give them the stiff arm.

Florida legislators aren’t sold on DeSantis’ plan. The state House offered up seven different alternatives, some of them conflicting, and announced they would put them all on the November ballot to let voters decide. The ideas range from completely phasing out property taxes over 10 years to capping the growth of the assessed value at 3% over three years for homestead property and 15% for everything else.

Requiring voters to sort this out is a massive “dereliction of duty,” Jared Walczak, vice president of state projects at the Tax Foundation, told me. “It’s not living up to the responsibilities of a legislature.”

George Kruse, a Republican Manatee County commissioner, gets it. He told the USA Today Network that DeSantis’ plan would turn these counties into “wards of the state.”

“The governor and the Legislature are only showing you one side of the ledger: Cut taxes and you’ll pay less,’’ he added. “Sure, that sounds good, It’s free ice cream. But what are you giving up?”

For starters, property owners would be giving up local control. Property taxes serve as a safety valve for local governments when state aid declines or the economy falters, Walczak argues. When communities are stung by a downturn in the economy, they can ask their voters if they want to raise taxes or face cutbacks in services. If voters don’t think they're getting value for their taxes, they can show up at county meetings, participate in local politics and defeat elected officials who don’t respond to them.

Eliminating property taxes puts local communities at the mercy of the state. If another recession hits, and states choose to save money by reducing aid to localities, “local governments would have very little recourse other than to accept the lost revenues, cut their services, and live within those reductions,” Walczak explained.

A better approach, Walczak argues in a series of papers, would be for states to carefully design levy limits that impose rate rollbacks at the county level. These policies respond to population growth and inflation while limiting revenue collection when property values rise.

It's also no surprise that many state lawmakers, buoyed by partisan gerrymandering, are increasingly daring to control local governments. As I documented last year, most state legislatures operate by minority rule — especially in Republican-controlled states.

Fortunately, voters in both Texas and Florida will have to approve any change to their state’s property tax system. They should be very wary. The right reforms can provide some needed relief, but eliminating property taxes is not free ice cream.

_____

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mary Ellen Klas is a politics and policy columnist for Bloomberg Opinion. A former capital bureau chief for the Miami Herald, she has covered politics and government for more than three decades.

_____

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments