Editorial: Tick, tick goes the Doomsday Clock

Published in Op Eds

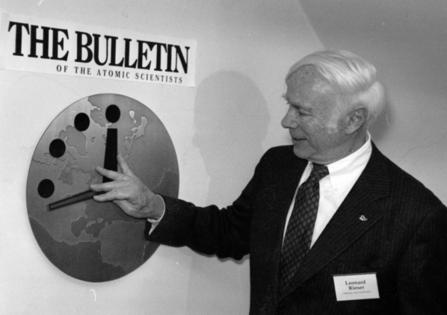

This month, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists at the University of Chicago is scheduled to announce whether the hands of its famous Doomsday Clock will move closer to midnight. It feels like a safe bet that Armageddon is drawing nearer today than it has in a long, long time.

The Doomsday Clock started almost 80 years ago, when physicists who developed the Bomb grew alarmed at its use against Japan to end World War II.

Between the late 1940s and the early 1990s, nuclear war wasn’t a remote possibility: It almost happened, repeatedly, as America and the Soviet Union fought the Cold War. Chicago’s atomic scientists moved the hands of their clock from seven minutes to midnight at its start in 1947 to just two minutes to midnight as of 1953, when the U.S. and Soviets started testing enormously powerful hydrogen bombs.

Fortunately for humanity, the 1990s ushered in a period of relative peace and proactive disarmament. In 1991, after the U.S. and Soviet Union signed the START treaty reducing strategic nuclear stockpiles, the clock was turned back to 17 minutes before the hour. The stockpile of nuclear warheads shrunk from more than 60,000 in the mid-1980s – an insane level of overkill – to an estimated 12,000. Test explosions became increasingly rare.

Today, unfortunately, the world is entering a new, more dangerous phase. The number of doomsday weapons and the number of countries wielding them threatens to grow. The clock gives humanity just 89 seconds to reverse course, its most perilous setting ever. Yet fewer people are paying attention,

The de-escalation that started in the early 1990s never would have happened without intense public pressure. That included mass demonstrations demanding an end to the arms race. And don’t underestimate the impact of 1980s movies such as “Threads” and “The Day After,” with their plausible depictions of death and horror after a nuclear exchange.

People in those days were scared, and rightfully so. Now, the fear factor is way down. It shouldn’t be.

New START, one of the landmark disarmament treaties that helped to pull the world back from the brink, is set to expire in February with barely a whisper of acknowledgement. In April, the United Nations will host a non-proliferation conference, and it appears likely that short-sighted national interests will outweigh concerns about the common good. Nuclear-weapons testing could make a destabilizing comeback in 2026.

Countries across the world are re-arming, as they recognize increased threats to their security. People forget that South Africa once had the bomb, and Ukraine was rife with atomic weapons after the fall of the Soviet Union.

Russia’s war on Ukraine is especially troubling. Drone incursions, sabotage and the vulnerability of nuclear reactors to attack is turning Europe into a dangerous flashpoint. The militarization of space, expanded anti-missile defenses and the potential risks of AI could create additional instability.

Proliferation is a red-alert risk again. One of arms control’s greatest successes — keeping the so-called nuclear club to nine countries — could fall by the wayside in short order.

When Ukraine agreed to give up the nuclear weapons on its soil in the mid-1990s, Russia provided a security guarantee that proved worthless. Now Europe has reason to doubt President Donald Trump’s commitment to NATO’s nuclear defense, forcing a reassessment among countries that depend on the U.S. for deterrence.

In Asia, South Korea and Japan are widely viewed as capable of producing nuclear weapons on short notice. With China and North Korea expanding their nuclear arsenals, and the U.S. increasingly viewed as unreliable, regional rivals may decide they need nuclear weapons for self-defense.

In the Middle East, Iran has flirted with joining the nuclear club for years. The joint U.S.-Israeli bombing of its nuclear facilities over the summer has driven the Iranian program farther underground, beyond the reach of international inspectors. If Iran gets the bomb, Saudi Arabia probably will want one too.

None of this is inevitable. It would be madness to resume nuclear testing, let treaties lapse and expand arsenals that already could wipe out the planet. Diplomacy worked for decades, mainly because of an understanding that avoiding nuclear war was essential to humanity’s future. Today’s global leaders need to start acting accordingly.

Submit a letter, of no more than 400 words, to the editor here or email letters@chicagotribune.com.

___

©2026 Chicago Tribune. Visit chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC. ©2026 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments