Why DEI isn't a success story at Seattle's tech companies

Published in Business News

For Monica Cisneros, her decade of experience in the tech industry as a product marketing manager has come with bigotry tied to her Latina identity.

Often, it's subtle slights rooted in prejudice. Colleagues ask the Texan where she's really" from. Misogynistic co-workers have told her they don't like her female voice, and have decided not to include her in deals because of it. They've also completely ignored her.

"It can go from microaggressions" — indirect but bigoted affronts, like assuming that a Mexican American colleague is an immigrant — "all the way to overt racism, which I have dealt with," said Cisneros, now a Seattle resident.

The city is a global hub for the technology industry, with its innovative giants and startups celebrated for changing society. The tech sector generates billions upon billions in profits and employs over 274,000 in the Seattle area, according to the Computing Technology Industry Association, a trade group.

Despite its successes, the industry has remained staggeringly white and male. Now, with corporate giants cutting thousands of workers to make way for more spending on AI, waves of layoffs signal that the small gains made by women and some tech workers of color could be lost.

Last year, across the state's tech workforce, only 3% of all tech roles were filled by Black professionals, and only 5% were worked by Hispanics and Latinos, according to the Computing Technology Industry Association. Women account for 25% of the tech workforce.

"Historically, I mean, the tech industry has been dominated by white, male professionals," said Marcus Courtney, a Seattle-based public affairs consultant on the government, nonprofit and business sectors, including the tech industry. "It's always been a boys' club."

The tech sector has largely been shaped by homogenous hands until recent years, and those leaders have been reluctant to let go of the reins. At Amazon, all seven executive officers are white, and six are men. Its 29-member senior team, or S-team, reflects more diversity, with 20 white men, four South Asian men, three white women and two Black women.

At Microsoft, five of seven executive officers are white, and four are men.

Both Amazon and Microsoft have faced gender discrimination lawsuits in recent years, with Amazon employees arguing that women are underpaid and Microsoft workers alleging bias against women. Allegations against Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates of inappropriate conduct toward female colleagues have also come to light.

In 2023, men held the overwhelming majority of positions in computer and information system management, at around 72%, according to database IPUMS USA, which uses U.S. Census Bureau microdata.

Courtney said large tech employers in Washington have shut out women, Latinos and the Black community, especially from engineering and coding roles.

The industry is even more competitive as of late, with Amazon recently laying off 14,000 corporate employees and Microsoft laying off more than 15,000 workers since May.

Some people who have made careers in tech told The Seattle Times that the industry has gradually embraced racial and gender diversity as corporate leadership recognizes its business benefits, such as access to a broader talent pool.

Cisneros, 32, isn't convinced. As she watches companies step back from their approaches to diversity, equity and inclusion by making cuts to diversity, equity and inclusion roles and employee resource groups, it leaves her feeling like those employers are disingenuous.

"A hostile environment"

Over the decades, Washington's tech industry has experienced highs and lows tied to gender and racial equity issues.

In the 1980s, "Seattle had some tech companies that were absolute leaders in gender issues," said Ed Lazowska, the Bill and Melinda Gates chair emeritus at the University of Washington. His example: Aldus Corp., a software company later bought by Adobe Systems, where many of UW's women graduates went to work.

That wasn't the case for the rest of the sector.

"Tech companies had what came across as a hostile environment" for women, Lazowska said. That included gender-based harassment, "locker-room talk" and workplace settings that Lazowska described as resembling "a boy's college dorm room."

The industry was also exceedingly white, but soon made space for some Asian workers.

In the aughts, Chengliang Zhang, co-president of the Seattle chapter of nonprofit Chinese Institute of Engineers, stood out: Back then, there were far fewer Chinese engineers, said Zhang, 49.

In the years since, a "significant change" has taken place, he added.

For other people of color, barriers remain.

Arif Gursel was an undergraduate studying computer science at Alabama's Tuskegee University, a historically Black university, in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

He remembers speaking with a Microsoft recruiter on campus and noticing a photo of a Black man among the company's promotional materials. Gursel said he wanted to connect with the man in the hopes of finding a mentor.

"The recruiter told me, 'Oh, sorry, he doesn't work at Microsoft. That's just a model we hired to be in the picture,'" Gursel said.

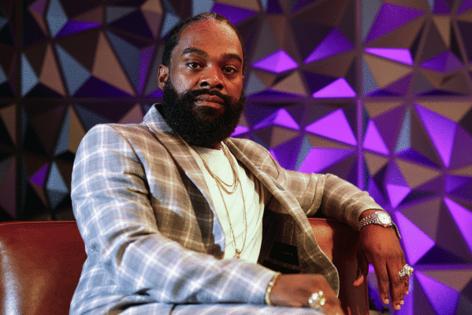

He took an internship with Microsoft and worked there for almost 12 years. Gursel, now 47, went on to fill leadership roles at Salesforce, Netflix and Google.

But as he rose through the ranks at major corporations, Gursel noticed fewer Black colleagues surrounding him with every promotion. Today, as the founder of a tech-driven nonprofit focused on empowering people of African descent, Gursel is one of the few Black leaders in Seattle's tech space.

After the 2008 recession and into the 2010s, the U.S. was swept with the realization that many people don't have access to tech jobs, said Jessica A. Lee, founder of Astute Strategies, a company that conducts inclusive economic strategy and research.

Two social movements — #MeToo, which decries sexual harassment and abuse around the world, and Black Lives Matter, a response to the 2013 acquittal of a Florida man who killed Trayvon Martin, a Black teenager — sparked social change felt within the tech industry, Lee said.

But professionals still say more needs to be done. Matthew J. Yazzie, 46, highlighted several obstacles for Native people trying to make it in the tech industry, though lack of representation rises to the top.

"The biggest hurdle that exists, just in general, is there's just no visibility of successful Indigenous individuals in tech," said Yazzie, who is Diné and grew up in the Navajo Nation. He started at Google in 2004 and worked there for close to seven years.

For Native people, community is a rarity in the tech sector, Yazzie said. Instead, they often find themselves in positions where they're forced to squash stereotypes and educate others.

Robin Máxkii, a Native technology activist in Portland, said remote flexibility was "a game changer" for Indigenous people like herself.

"For a lot of Indigenous people, remote work wasn’t just about convenience, it was access," said Máxkii, whose tribal heritage includes the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohicans. Working from home allows Native people to "show up fully" without the added financial and emotional pressures that an office culture can create, she added.

While tech companies put money toward aesthetics and amenities, "they weren’t investing in diversity pipelines, mentorship programs, or career development for Indigenous people," Máxkii said, "which sends a clear message that appearances matter more than structural change."

Fast-forward to this year. President Donald Trump's administration has rejected DEI policies across federal and corporate entities nationwide. Many of these policies were implemented in the wake of the 2020 murder of George Floyd, a Black man, by a white police officer in Minnesota, and the #MeToo revelations against top tech leaders.

An LGBTQ+ nonprofit leader declined to speak to The Times on record for the story, citing dangers currently faced by their community and concerns about being targeted.

'Consequences of being your true, authentic self'

Cisneros, the product marketing manager, found her first role in the tech industry at software company TIBCO through Las Comadres Para Las Americas, a Latina support network.

After about four years with TIBCO, she was recruited by Alteryx, another software company, in 2021. Alteryx went above and beyond to create an inclusive culture, she said, through its employee resource groups and well-trained human resources professionals.

To build tech careers, people of color and women like Cisneros must overcome long odds, but the fight for equity and acceptance doesn't end once they're on the job.

Cisneros said that, throughout her career, she's been supported by managers, but "you don't see a lot of Latino leaders out there."

She said she sometimes found herself the only Latina in the room.

In her Mexican American community, people sometimes don't know that tech jobs exist, she said.

For many young professionals who didn't attend esteemed high schools that supply prestigious universities, networking can be tough without alumni support.

And even when tech jobs are clinched, the social aspects of work aren't open to all.

"There's this thing about blending in: I don't think we should," Cisneros said. However, she added, "there will be consequences of being your true, authentic self."

Cisneros parted ways with Alteryx in 2024. She's currently the vice president of community for the Association of Latino Professionals for America's Seattle chapter, but she said she's watching their programming shrink as funding, including corporate sponsorship, dries up.

For now, Cisneros is back on the job market — in search of a workplace that aligns with who she is.

"I just want to do my job," she said. "I just want to write emails. I don't want to talk with HR.

©2025 The Seattle Times. Visit seattletimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC

Comments