Microsoft critics say complaints about Israel work go 'into a void'

Published in Business News

REDMOND, Washington — Two months after Microsoft for the first time restricted services to an Israeli military unit, protesters were again on the company’s doorstep to demand Microsoft sever all ties with Israel’s government.

On a chilly Tuesday morning in Redmond, pro-Palestinian activists beat drums, waved flags and pointed megaphones toward Microsoft’s headquarters chanting demands they’ve repeated for most of the year.

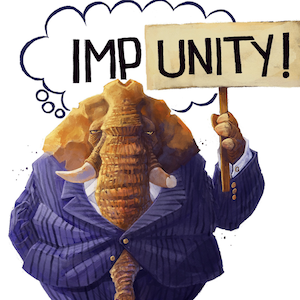

Microsoft has acknowledged that Israel misused some of its cloud technology, and moved to limit one Israeli military unit’s use of those services. That hasn’t satisfied protesters — who have disrupted high-profile Microsoft events and invaded Microsoft President Brad Smith’s office — or resolved a significant morale problem for the company.

A group called No Azure for Apartheid, made up mostly of former Microsoft workers, is maintaining calls for the company to sever all ties with the Israeli government.

During previous protests, members of No Azure for Apartheid clashed with police and private security at one of Microsoft’s marquee conferences held in May at the Seattle Convention Center. In August, they escalated tactics by occupying a plaza on Microsoft’s Redmond campus and breaking into Smith’s office to stage a sit-in.

But Tuesday’s rally had a different strategy. One of the group’s leaders said not to harass employees but rather try to engage with them as they walked. They said not to trespass on the campus but rather stay on public sidewalks and walkways.

The roughly two dozen protesters began their rally at the Redmond Technology Station and walked to the pedestrian bridge that connects the two halves of Microsoft’s campus on either side of Highway 520. They continued to chant, accusing Microsoft and its executives of profiting off the Israel-Hamas war and linking the company’s technology with accusations of war crimes in Gaza and the West Bank. Protesters also handed out flyers to Microsoft employees and other passersby.

As chants and steady drumbeats echoed across the highway, No Azure for Apartheid protesters in San Francisco were setting up a rally at Microsoft’s Ignite conference. The conference started Tuesday and runs through Friday.

On Tuesday, a member of the audience disrupted a conversation between Microsoft’s CEO of commercial business, Judson Althoff, and Adobe CEO Shantanu Narayen. Similar to disruptions during previous Microsoft events this year, the protester said they were a Microsoft employee who was resigning in protest of Microsoft’s ties to Israel.

“We are aware of the activity. Appropriate teams are engaged to help minimize these disruptions,” a Microsoft spokesperson said in an emailed statement. “We respect the right to peaceful assembly and ask that it be done in a way that does not cause business disruption.”

The dual rallies, hundreds of miles apart, are part of the group’s latest plans to expand, said Vaniya Agrawal, a former Microsoft employee who was fired after she disrupted a panel between CEO Satya Nadella and former CEOs Steve Ballmer and Bill Gates in April.

“We’re escalating by growing the movement globally,” Agrawal said. “We’re trying to take this fight and assert ourselves everywhere Microsoft goes.”

Microsoft has felt the pressure over its work with the Israeli government, but the company has maintained that the action it’s taken is more of a result from reporting in The Guardian, not No Azure for Apartheid.

After The Guardian reported earlier this year that the Israel Defense Forces were deepening ties to tech companies and their cloud systems to store intelligence data, Microsoft conducted an internal review of how its technology was used.

The company said in May that it found no evidence of its technology used to harm or target people in Gaza.

In August, The Guardian and two regional publications — +972 Magazine, an Israeli-Palestinian outlet, and Hebrew-language outlet Local Call — reported that Israeli military spy agency Unit 8200 was using a Microsoft cloud computing server to store surveillance data, including phone calls, on civilians in Gaza. That reported triggered an independent investigation by Microsoft and the company eventually said it found evidence that supported some of the claims and cut off specific services to Unit 8200.

Microsoft’s latest action came earlier this month, when Smith announced in an internal memo that the company had set up a new way for employees to flag concerns over how technology was used.

Agrawal said she heard about the update and found it “infuriating.”

“These so-called channels have always existed,” she said. “Our members have tried to use channels that exist to give feedback and raise concerns.

“It’s just another way to funnel the anger of Microsoft employees into a void.”

No Azure for Apartheid is a Microsoft-focused group, but it’s part of a larger network of organizations leading the backlash against tech’s ties to the Israeli government.

Holding a megaphone and leading the first chants Tuesday was Ahmed Shahrour, a former Amazon employee who said in September he was suspended after urging workers to protest the company’s relationship with Israel. His primary target was the $1.2 billion cloud-computing contract that Amazon and Google have with the Israeli government called Project Nimbus.

Shahrour shared messages throughout internal channels, calling for workers to join a “new, worker-led Palestinian resistance” at Amazon called the Amazon Worker Intifada. He was fired last month.

Shahrour, who is Palestinian, said Tuesday his dream was to be a software engineer for Amazon’s retail business. He became an engineer for Amazon-owned Whole Foods based in Seattle. But as the Israel-Hamas war stretched on and he learned about Project Nimbus, he felt uneasy while working for Amazon.

He started participating in No Azure for Apartheid protests. He joined them during the Microsoft Build conference rally in May, then the encampment-style protest in August and soon after the sit-in in Smith’s office.

“It felt very empowering,” Shahrour said. “It was like, OK this is it, I need to bring it to everyone’s attention. Everyone needs to know about Project Nimbus and tech’s complicity.”

©2025 The Seattle Times. Visit seattletimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments