Column: How little books, millions of them, helped in Word War II

Published in Books News

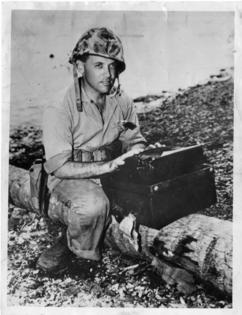

CHICAGO -- I have a photo of my father, sitting on a log on a beach somewhere in the South Pacific during World War II. Herman Kogan was a U.S. Marine Corps sergeant, a combat correspondent who fought in and reported from battles at Guadalcanal, Okinawa and elsewhere and, of course, made it home safely to Chicago.

He wrote stories for the Chicago Tribune during the war, and he read books too. I look at this photo and imagine one of those books tucked in a pocket of his fatigues, and I know that he was not alone, because more than 120 million books found their way to soldiers fighting in WWII.

He did not talk much about the war as I was growing up, but he did tell me about some of the books he read when the guns were silent. It is one of the most remarkable if relatively forgotten stories of that war, but this books-in-battle tale came rushing back with the release of the latest limited edition from the ever-imaginative company called Field Notes.

Four times a year or so since its founding in 2007, this local outfit has come forth with these limited editions. The previous 68 of them have featured such topics as baseball, dime novels, space flights, national parks, the Great Lakes, and on and creatively on.

This new one is called “1943” and was inspired by Armed Services Editions, a series of fiction and nonfiction books published and distributed to the U.S. military from 1943-47. More than 120 million copies of 1,200 titles went to troops in a small paperback format designed for a soldier’s pocket.

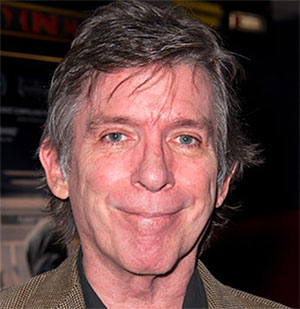

The story came to the attention of Field Notes recently when one of the company’s recently hired young designers, Casey Rheault, found some images of the ASE books online. He showed them to Field Notes boss Jim Coudal, asking him, “Have you ever seen these?” Coudal had not, and later that day, he bought some historic examples on eBay.

Coudal explains the Field Notes philosophy to me: “We like digging deep on subjects. We like selling notebooks, and we like telling stories. This edition ticked all those boxes. We don’t worry about things, we just take it on faith that if we are curious about something and excited about the process, people like us will dig it too.”

The “1943” edition “mimics the ASE’s horizontal orientation. While they’re our usual 5.5″ x 3.5″ memo book size, they’re the first with two staples on the short side instead of three on the long side.” They come in bright red, yellow and blue.

Coudal had made a call to his friend, novelist and frequent collaborator Kevin Guilfoile, to share his excitement about this project. And they have come with something extra, inspired by the “gold mine” found in their digging and reading “When Books Went to War,” a 2014 book by Molly Guptill Manning.

The book has inspired a rare Field Notes podcast featuring Guilfoile in conversation for an hour with the lively and smart author.

But wait, there’s more, and it comes in the form of Samuel Dashiell Hammett’s “The Maltese Falcon.” Though Guilfoile writes it “was never published as an Armed Services Edition, it is the type of sexy, gritty, realist novel that undoubtedly would have been a favorite among the troops.”

It is published now as a Field Note Brand Books release, available as part of a “1943” package or as an individual title. It’s the second such book, following Guilfoile’s “A Drive into the Gap,” about baseball and fathers and sons and which Pulitzer Prize-winning Chicago author Jonathan Eig called “extraordinary, (a) beautifully written story about baseball and memory. Simply amazing.”

Guilfoile also tells of the happy fate of what many consider the great American novel, “The Great Gatsby.” Most forget that it attracted only modest attention and sad sales when first published in 1925. But after it was reprinted as an ASE, it was, Guilfoile writes, “a huge hit. … (It) almost certainly would never have made it to your 21st century high school reading list if not for the ASE program.” (Poor F. Scott Fitzgerald would never know; he died in 1940.)

Guilfoile also gives us the censorship-shadowed publishing history of “The Maltese Falcon,” which was first published as a serial across five issues of Black Mask Magazine and he solves one of the mysteries of the 1941 film version of the book, which starred Humphrey Bogart as private detective Sam Spade. Guilfoile writes of a seminal line in the film, when Bogart refers to the falcon as “the stuff that dreams are made of.”

As Guilfoile explains, “This, the most famous line from the film, does not appear in the novel or the screenplay. It’s adapted from Shakespeare’s “The Tempest,” and legend has it that Bogart suggested it to (director John) Huston on set, while shooting the film’s final scene.”

That’s good to know. As for the entire ASE saga, Guilfoile says that it “transformed many soldiers into passionate readers, … comforted millions of people in battle zones, and fostered a culture of reading. … The program turned forgotten works into beloved classics, expanded the market for affordable books, and promoted literature for both entertainment and the public good.”

There exists only one complete set of the books, and it resides at the Library of Congress. Individual books for sale pepper the internet. Many libraries hold some. I am holding one of them, “You Know Me Al” by Ring Lardner, once a writer at this paper. It’s worn, its pages a bit darkened and a few torn and tattered and all that tells me is that once a soldier had it in his pocket, somewhere, long ago.

©2026 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments