Medetomidine is replacing xylazine in Philly street fentanyl − creating new hurdles for health care providers and drug users

Published in Health & Fitness

Philadelphia’s street opioid supply – or “dope” market – is constantly changing. As health care workers and researchers who care for people who use drugs in our community, we have witnessed these shifts firsthand.

New adulterants are frequently added to the mix. They bring additional and often uncertain risks for people who use drugs, and new challenges for the health care providers and systems who treat them.

The latest adulterant to dominate the supply is medetomidine.

Medetomidine, pronounced meh-deh-TOH-muh-deen, is a drug used in veterinary medicine for sedation, muscle relaxation and pain relief, often during surgery. It is an alpha-2 adrenergic agonist, which essentially means it works by slowing the release of adrenaline in the brain and body.

In May 2024, the Philadelphia Medical Examiner’s Office began testing for medetomidine in people who died from fatal overdoses. By the end of the year, 46 of the deceased had tested positive for the substance, in addition to fentanyl and other known chemicals.

In fact, medetomidine is quickly becoming more common in Philadelphia’s street opioid supply than even xylazine, a non-FDA-approved sedative linked to skin ulceration, chronic wounds and amputation.

Xylazine was first detected in Philadelphia street drugs in 2006 and became increasingly common starting in 2015. By early 2023, xylazine was detected in 98% of tested dope samples in the city.

However, its presence is steadily dropping, according to local drug-checking program data. The Philadelphia Department of Public Health says medetomidine has emerged as a primary adulterant and is now twice as common as xylazine in drug-checked samples.

Recent studies show even more unusual substances entering the street fentanyl supply, such as the industrial solvent BTMPS.

At the same time, hospital and behavioral health providers are reporting more common presentations of severe withdrawal symptoms among people who use drugs in Philadelphia.

While medetomidine’s sedating effects are similar in mechanism to xylazine, it is upward of 10-20 times more potent. It suppresses brain signals in the central nervous system, leading to deep sedation.

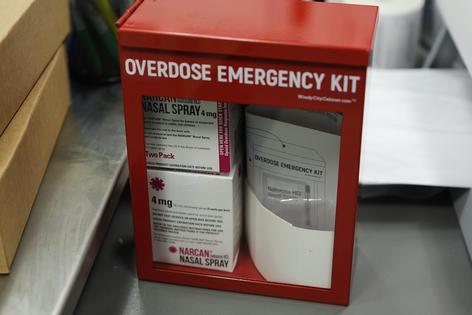

Since medetomidine is so powerful and does not act on opioid receptors, a person who overdoses on it often does not respond to the opioid-reversal drug naloxone, which goes by the brand name Narcan, in the manner we commonly expect from people who appear to have overdosed on opioids.

When patients overdose on a combination of opioids and medetomidine, providing naloxone will help individuals start breathing again but does not reverse the sedation caused by the medetomidine.

From our clinical experience, after patients start to breathe normally, providing additional doses of naloxone does not seem to help and even risks prompting opioid withdrawal symptoms.

Additionally, medetomidine presents serious clinical challenges for health care workers treating patients in withdrawal. These patients often experience symptoms such as rapid heart rate, severe spikes in blood pressure, restlessness, disorientation and confusion, and severe vomiting. While many of these symptoms were similar, if less intense, for those withdrawing from opioids and xylazine, the number of patients we are seeing is unprecedented – as is the severity of their symptoms.

While published data on humans’ withdrawal from medetomidine is limited, clinicians are drawing comparisons to dexmedetomidine, a related drug used in humans that has shown similar features when withdrawn too quickly.

Researchers and clinicians in Philadelphia’s hospitals, including us at Thomas Jefferson University, are analyzing emerging clinical data. This data suggests that existing protocols that effectively controlled withdrawal symptoms in the era when xylazine was common are no longer adequate in the era of medetomidine. New protocols have been developed based on the guidance of local experts and are being tested.

The rise in severe withdrawal symptoms has prompted expanded testing for adulterants such as medetomidine in Jefferson’s emergency departments.

Currently, drug testing involves two primary approaches. Qualitative analysis determines the presence or absence of substances. For example, fentanyl and xylazine test strips are commonly used by harm reduction groups and people who use drugs. Unfortunately, they can be unreliable and prone to user error, expiration, misinterpretation and false positives or negatives. This technology is also commonly used in urine drug-testing kits sold over the counter.

Quantitative analysis, on the other hand, is a more sophisticated approach to drug testing. It uses complex technology such as liquid-phase chromatography and mass spectrometry to separate the individual components of a sample and determine their concentration. This form of testing is more expensive and requires specialized equipment and analysts to perform the tests and interpret the results.

Hospitals in the city have begun selectively testing urine and blood samples from patients who present with suspected medetomidine exposure. The labs are looking for the presence of certain drugs and their related byproducts, and also trying to identify distinct concentrations that might be associated with overdose, intoxication and withdrawal.

We believe Philadelphians should be aware of these recent changes in the street drug supply and how people in their communities may react to exposure to medetomidine.

Naloxone is still recommended for a person showing signs of opioid overdose – such as excess sedation, shallow or absent breathing and small pupils. Narcan is freely available at pharmacies around the city. But if the patient starts breathing but does not immediately wake up, additional doses of naloxone should be avoided.

As always, contact 911 for expert assistance and to get patients to an emergency department to complete their care.

Patients who use large amounts of drugs may suffer from severe withdrawal symptoms. Typical medications given to those in opioid withdrawal, such as buprenorphine or methadone, may not be sufficient to treat this constellation of symptoms. Even medications and regimens tailored for xylazine may not be effective.

Patients with severe withdrawal symptoms need to be seen in the emergency department, given the risk of undertreating this emerging condition.

Read more of our stories about Philadelphia.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Kory London, Thomas Jefferson University and Karen Alexander, Thomas Jefferson University

Read more:

Philly hospitals test new strategy for ‘tranq dope’ withdrawal – and it keeps patients from walking out before their treatment is done

Philly’s street fentanyl contains an industrial chemical called BTMPS that’s an ingredient in plastic

How opioid deaths tripled in Philly over a decade − and what may be behind a recent downturn

Kory London receives funding from The Sheller Family Foundation.

Karen Alexander receives funding from the National Institutes on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

Comments