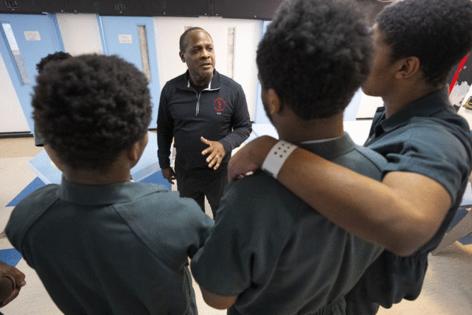

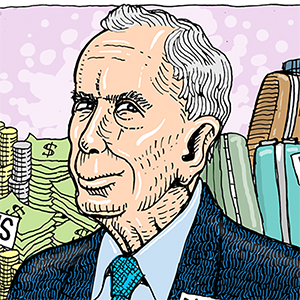

Mentoring the kids 'typically nobody else loves': Pastor Damone Jones has dedicated his life to guiding and supporting children charged with murder

Published in Lifestyles

PHILADELPHIA — For the last three decades, the Rev. Damone Jones has worked to build relationships with Philadelphia's most troubled children, the teens he says "typically nobody else loves": those charged with murder.

Several days per week, the West Philadelphia pastor visits the young men under 18 who are held in a city jail, and offers them guidance and support.

He provides the boys with clean underwear, socks, and toiletries, and through his nonprofit, the Brothahood Foundation, he hosts biweekly basketball games inside the jail that introduce them to the positive role models that many have lacked and needed in their lives. He sits with them for lunch, hires a barber to cut their hair, and attends their court hearings. In some cases, he testifies at their sentencings — often the only person willing to do that.

But most of all, he helps them confront the pain they have caused and experienced, and counsels them as they come to terms with what they have done — and the decades of their life they will likely spend behind bars because of it.

"Jesus said, 'I was in a prison and you came to me,'" he said. "It doesn't negate what landed you there."

Jones' work has led him to become a father figure, mentor, and confidant to dozens of young men whose mug shots have flashed across Philadelphians' television screens and social media feeds.

There is Ameen Hurst, the 16-year-old who killed four people, then escaped from jail. Troy Fletcher, who at 15, fired dozens of shots outside Roxborough High School, killing Nicolas Elizalde. And Michael Moore, who was arrested for killing a man at just 13 years old — making him one of the youngest people in Pennsylvania history to be charged with murder at the time.

Many of them have come to call Jones Dad. They reach out almost daily, calling and mailing him drawings and handwritten letters filled with their late-night thoughts, fears, and regrets.

And Jones, too, accepts them as part of his family.

The work, all unpaid, is a calling from God, he said — a responsibility to be there for the young Black men he believes society has largely failed. All will eventually be released, he said, and "what are they coming back to?"

"Who will they be?" he asked.

Jones, 59, has earned the respect of Philly's top leadership. District Attorney Larry Krasner called his work "groundbreaking." Mayors have appointed him to various agency boards. The Philadelphia Department of Prisons wants to expand his reach to adults.

But Jones' heart is with kids, he said, the city's most broken young men, a population forgotten by most, but whom he sees as his children.

The guiding principles

On a recent visit to Riverside jail, Jones walked through the cell blocks where the teens spend their days.

"Doc! Doc!" two young men cheered when they saw him, a nod to his doctorate in ministry. They ran over for a hug.

Jones can name each of the 18 juveniles held there. For most, he can recall the neighborhood they are from, the basics of their criminal case, and the tragedies of their young lives: abuse, drug use, deep poverty, absent parents, witnessing violence.

He has seen, he said, how just a little love and structure can transform a teen in just a short period of time.

"They become people who are different than who the prosecutor knows only from a docket," Jones said. "They paint a picture of this animal who can't change. But they grow, they mature. Two years is a long time for a teenager."

Jones' upbringing was dramatically different from that of most of the boys he works with. He grew up near 63rd Street and Lansdowne Avenue in West Philadelphia, raised by loving parents in a Christian home.

His dad showed him the importance of a father figure, and his Bible study teacher taught him that the work outside church matters just as much as, if not more than, the work inside.

Not long after Jones became a minister at 21, that teacher invited him on a visit to Holmesburg Prison, the now-closed facility in Northeast Philly.

Jones was skeptical, but reluctantly agreed to go.

"That's where all of the stereotypical images of inmates that I had and held melted," he said.

He went on to visit other adult prisons, before meeting the Rev. James Hazzard, Philly's juvenile jail chaplain at the time. He realized there that working with children was his passion.

"Everything I learned about working with incarcerated juveniles, I learned from him," Jones said of Hazzard, who died in 2004. "And everything he taught me, I still practice to this day. And it works."

Among those principles:

1. See every child as a person, as family, and as valuable. Make clear that you care more about them, and their well-being, than their case.

2. Do not be afraid to physically embrace them. Many of the kids, he said, have been physically and sexually abused, and have never experienced healthy physical touch in their lives. Hugs are an essential greeting.

3. "Shut up and listen." Kids will shut down if they don't think you understand or hear them. Stop assuming what they are dealing with and where they came from, and let them talk.

Jones went on to earn a doctor of ministry degree, and in 1995, he became the pastor of Bible Way Baptist Church, at 52nd and Master Streets, where he remains today. He and his wife, Melissa, a therapist, have four adult children.

Fast-forward to 2011, when then-Mayor Michael Nutter appointed him to the board of the Philadelphia prisons, giving him greater access for the first time to young people at the jail on State Road. He started visiting the juvenile unit and spending time with the young men, bringing in public speakers and counseling them.

He almost walked away in 2016, at the start of then-Mayor Jim Kenney's first term. The conditions inside the jails were deteriorating and unsafe, and yet the city "always painted a picture that everything was wonderful," he said.

On what he thought was his final day inside the jail, he ran into a young man named Malik Manson, and said he might not see him again. The politics in the prisons, he told him, had grown too frustrating to watch.

Manson grew quiet and looked at him.

"You ain't here for them," he told the pastor. "We need you."

He has continued the work ever since.

The young men he's helped

The walls of Jones' office tell the story of his journey. A brick from Holmesburg. The canvas painting of a Black man with an American flag noose around his neck. Manson's quote.

And there are photos of the four dozen young men he holds closest to his heart, framed and hanging next to his desk.

Michael "Kyle" Moore is among them.

Moore met Jones after he had been in custody for about two years, charged with killing a 25-year-old man in retaliation for the shooting of his cousin. Moore was 13 at the time of the shooting.

Born and raised in North Philly, near 22nd Street and Lehigh Avenue, Moore had a childhood defined by poverty, neglect, and trauma. With an unstable home and absent parents, he sought friendship and support from older people in the neighborhood who sold drugs. By the fourth grade, he was truant in school, and by 10, he was drinking, smoking, and later, using pills.

Then, in 2010, he was charged with murder.

Moore had been holed up inside his cell at the Philadelphia Industrial Correctional Center for about a year when prison officials asked Jones to pay him a visit. They were worried about the teen, who wasn't eating and didn't want to talk to anyone.

Moore, now 28, remembers ignoring the pastor at first. He was just there to preach at him, he thought, and would never understand him.

But Jones kept returning, and soon, Moore started to open up. Jones brought him some books, like "Letters to an Incarcerated Brother" and "The New Jim Crow." Moore devoured them, and they started a miniature book club.

"He started helping me without me knowing that I was being helped," he said.

The pastor taught Moore how to deal with his emotions and open up about his traumas. Through reading and writing exercises, he expanded his vocabulary. He slowly started working to repair his relationship with his mother and siblings.

"For a long time, I couldn't see how big the world really was, and how limited my thinking was by the people that I was around," he said.

Moore was later convicted and sentenced to 25 years to life in prison, but by then, he said, he felt prepared to begin his sentence. He could better control himself and interact with others, and was ready to use the time to work on himself.

He stays in regular contact with Jones, who still sends him money for commissary, clean clothes, and a tablet for his cell. Moore hopes to work alongside Jones when he is released.

"Everything I am, everything I say, Dr. Jones taught me," he said.

It was a common sentiment among the young men he has worked with. Cameron Choice, who at 15 years old, shot into a crowd in Fishtown and wounded seven people in 2021, said in an interview that Jones helped him feel like he had "another chance at life."

DeAndre Wiggins, who is serving 30 to 60 years for murder and aggravated assault, calls the pastor Dad — "the perfect person to help me along this journey we call incarceration."

"Sometimes I feel hopeless, and then I remember I have people like you," he wrote to him in a letter.

He signed it, "I love you."

From basketball to mentoring

Jones created his nonprofit, the Brothahood Foundation, in 2019 to help pay for basic toiletries like toothpaste and deodorant, socks, and underwear for young men in jail. The prisons provide each boy with one pair of each, and most cannot afford to buy extras, he said.

The organization also hosts a basketball game with the teens every other week, where Jones and about a dozen other men from the community gather for an hour-long game, then break out into small group conversations for about 45 minutes.

The goal, he said is to "let them breathe, let them be kids, let them laugh," he said. "Because they don't get to do it very often."

On a February night, after the team of teens won the game, Khalil Rogers gathered in a circle with about four young men. Their conversation on the Eagles' Super Bowl prospects soon merged into a question of leadership and respect.

"What's your next goal?" Rogers asked the boys.

"Take some college courses," said one teen.

"Get out of jail, and take care of my daughter," said a 16-year-old charged with double murder.

Jones' work is not without critics. Families of victims have asked how he could support a murderer. Prosecutors and judges in court have cast doubt on how he and other mentors in the Brothahood Foundation could truly get to know a young person through hour-long visits. Some have shown open contempt for the program.

The pastor is careful about what he says in court. He sticks to what he has observed — how he says a teen's demeanor has changed over time, from being angry and antisocial to becoming a leader on the basketball court and the cell block. To him, he said, those small changes show growth, promise, the ability to be rehabilitated.

And, he said, just because he works with offenders does not mean he doesn't feel for victims. His brother-in-law was killed in a homicide in Baltimore last year, and he has lost other friends to violence.

"I have been on both sides here," he said. "We work hard to help the kids accept responsibility.

And while he is careful not to discuss kids' open cases with them in detail, the private conversations could, in theory, expose him to being subpoenaed. No prosecutor has tried it yet.

"There's not gonna be a day where I tell the court what a kid tells me," he said. "The day that happens is the day I need to give this up."

Saying goodbye

There's a pain that comes with caring for this group of young people. He spends years getting to know teens, only for them to be sent to a state prison hours away, handed decades-long sentences. He doesn't know when, if ever, he might see them again — or if he will even be alive by the time they are released.

"They become like family to you," he said, "I never anticipated that when I started. When they get sent upstate, it's a loss."

The distance has made it challenging to visit, he said. He is working on organizing a trip to State Correctional Institute Pine Grove, about 300 miles away, where a core group of young men he mentored are now held.

His hugs with teens get tighter the closer they get to sentencing, he said. Earlier this year, after spending 2 1/2 years with Troy Fletcher, one of the teens responsible for the fatal shooting outside Roxborough High, it was time for Fletcher to begin his 25- to 50-year sentence.

Jones gathered with the boys for their basketball game, and afterward, Fletcher pulled him aside.

Fletcher is usually one to joke around and not take things seriously, Jones said. But this time, the 17-year-old looked deeply into his eyes and said: "I just wanted to say thank you."

He was grateful for the time he had spent with Jones, he said, and was ready to start serving his time — to move toward what the rest of his life will be like for at least the next quarter century.

The pastor usually tells young men that he will be there for them when they get home. But in Fletcher's case, Jones will be close to 90 by the time the teen is free. He couldn't make that promise.

Jones' eyes welled with tears. He told Fletcher he could do this.

They embraced. And it was a little bit tighter.

©2025 The Philadelphia Inquirer, LLC. Visit at inquirer.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments