Signs of dyslexia and reading troubles can be spotted in kindergarten -- or even preschool

Published in Lifestyles

LOS ANGELES — This year, for the first time, California schools will be screening kindergarteners, first- and second-graders for reading difficulties, including dyslexia, under a state mandate signed into law by Gov. Gavin Newsom in 2023.

Such early identification of reading struggles is key to getting young children the needed interventions before they fall too far behind. California — with reading scores below the national average — is the 40th state to mandate such a screening.

But can a 5-year-old, who can't read yet, be screened?

While reading itself is a learned skill, research has found that the brain structures connected to literacy begin developing right after birth and continue across the first few years of life. The earliest signs of reading differences and dyslexia can be spotted in preschool — and perhaps even earlier.

The new California screening is intended to identify children with reading difficulties who could benefit from additional help. It can also flag children for early signs of dyslexia — but is not intended to formally diagnose a learning difference.

Instead, the screeners are carefully crafted to test the pre-reading skills that form the building blocks for literacy, including a child's ability to manipulate sounds, name objects, and remember a list of words.

"The earlier, the more plastic the brain is, and the better the response will be, so you can avoid problems down the line," said Dr. Marilu Gorno-Tempini, a behavioral neurologist at UC San Francisco who helped develop one of the four state-approved screeners. "It's preventative medicine."

The earliest signs of dyslexia in a preschooler

Megan Potente of San Francisco grew up with a brother who had dyslexia, so she wasn't surprised when she started noticing some familiar signs when her son was in preschool.

He was a bright and engaged child, and he didn't seem to have a language delay. Yet he didn't seem interested in letters or rhyming the way his older sister had, and he had a very difficult time learning to write his name.

But the brightest flag came during a preschool performance. "He was the kid standing in the front who obviously didn't learn the song. It was so hard to watch," said Potente, who is the state director of Decoding Dyslexia CA, a grassroots group of parents of children with dyslexia.

Potente said if her son had been screened for reading difficulties in kindergarten, he might have gotten help earlier. Instead, he didn't learn to read until he was 10, after attending a school for children with dyslexia.

Gorno-Tempini said difficulty rhyming and remembering words could be common signs of dyslexia in preschoolers. In early elementary school, children may struggle with their working memory, including learning simple children's songs. They may ask a parent to go back and reread an early part of a book because they can't remember what just happened.

Many also have difficulties learning their colors or the names of animals, because words do not stick to their associated objects, she said.

Rhyming, meanwhile, is an early part of phonological awareness — the ability to recognize and manipulate sounds in oral language. If a child has trouble with rhyming, or doesn't seem to enjoy playing with rhymes, Gorno-Tempini said this could also be an early indicator of dyslexia.

Stephen Mutkoski of Manhattan Beach said his son struggled to learn the alphabet song, and had trouble saying words that begin with the letter S. "Instead of saying Snake he would say Nake, and instead of saying School he would say Cool," said Mutkoski. He was later diagnosed with dyslexia.

Sound reversals are another early sign, Gorno-Tempini said. While mispronouncing San Francisco as Fran Sansico can be an adorable part of language development for the youngest children, she said, if it persists after age 4 or 5, such verbal expressions might indicate a need for extra help to prevent later issues.

In the future, Gorno-Tempini said, she hopes 4-year-olds will be eventually be screened in transitional kindergarten so that teachers will be able to intervene even earlier.

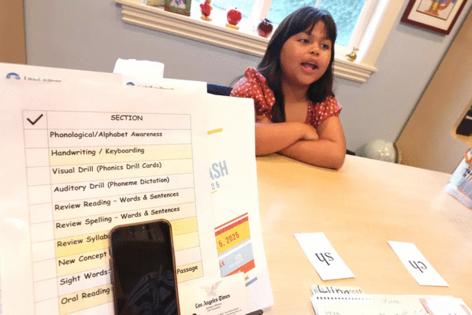

How do the new reading screeners work?

Kindergartners will be given the screeners individually. The screeners are computer-based and take about 10 to 15 minutes.

Most schools will wait until at least November to give the screeners to kindergartners, to first allow for a few months of letter instruction before checking if children are behind, said Leslie Zoroya, who leads a literacy initiative at the Los Angeles County Office of Education.

Ideally, she said, the screeners will be administered several times during the year to monitor how a child is learning and whether interventions are working.

The screeners are adaptive, and programmed to push on areas where a child may be struggling.

In kindergarten, the test uses letters as well as visual symbols to check for a range of skills, such as alphabet knowledge, object naming, vocabulary, and phonological awareness.

One part of the screener asks children to manipulate the sounds in a word orally, said Gorno-Tempini. For the word "cat," for example, they must be able to segment the sound C-A-T, and then figure out what happens if they remove the C- sound.

In another section, children are given a list of objects and asked to name them as quickly as possible. Difficulties retrieving the sounds of these words is one early indicator that a child may have reading difficulties in the future. .

In first and second grade, to check their auditory memory, a child might be asked to remember and then repeat a sentence or list of items.

In another section that checks for a child's ability to hold attention and process visual information, students might be shown a list of symbols; one symbol is taken away, and the child is asked to remember which one is missing.

Once a child at risk is identified, what happens next?

The screeners are designed to alert teachers where a student's strengths are, and where a child's skills may need additional support.

"That's the information that a classroom teacher needs to be able to address a problem early so they're not just guessing," said Zoroya. "Instead, a teacher will know, "you need help with 's' and 'sh' sounds. You can't hear the difference between those. Let's work on that."

Children can then be broken out into smaller groups to receive targeted instruction, given extra time to practice and then tested again.

"You want to address the deficit in kindergarten and follow it so you can make sure kids aren't going to middle school without these basic skills," Zoroya said.

Some children may need further assistance, such as help from the school's reading interventionist.

If the problem persists, a child can be referred out for an outside evaluation, where they might be formally diagnosed with dyslexia or another reading disability and given more intensive tutoring.

____

This article is part of The Times' early childhood education initiative, focusing on the learning and development of California children from birth to age 5. For more information about the initiative and its philanthropic funders, go to latimes.com/earlyed .

©2025 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments