He wants to be composted after he dies. Here's how he plans to do it

Published in Lifestyles

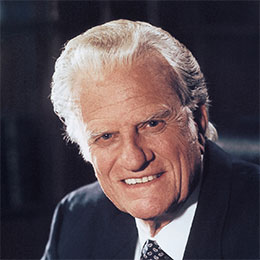

PHILADELPHIA — Paul Meshejian, a 76-year-old retired actor who lives in Philadelphia, said he never liked the idea of his body being embalmed and taking up land in an expensive box. The remaining spots in his family's plot and cemetery have already been claimed anyway.

Cremation, he said, is "a waste of energy and throws a lot of pollution into the atmosphere."

So when he heard about human composting, he was all in.

"When's the last time you walked through a cemetery and just stopped in front of a random headstone, and said, 'I wonder what that person's life was like'?" he said. "My ego is not that big," he added with a laugh.

Meshejian has arranged for his body to be composted by the West Coast-based Earth Funeral, one of a handful of companies that legally compost bodies, with an average price tag of $5,000.

Once Meshejian dies, the company will wash his body before wrapping it in a biodegradable shroud and putting it inside a vessel with mulch and wildflowers. After a 45-day process, his body will emerge in the form of enough "nutrient-rich soil" to fill the bed of a pickup truck.

Human composting, also known as natural organic reduction or terramation, is not yet legal in Pennsylvania. Neighboring states have been legalizing the process, but since the nascent industry does not have a facility on the East Coast yet, people have been shipping bodies across the country to take part.

Meshejian's loved ones will be able to receive small containers of his soil. He thinks it could be romantic for it to be sprinkled over his wife's grave. The rest will be donated to conservation efforts, though picking up all the soil for a separate planting project is also an option.

"It seems well thought out and makes sense to me," Meshejian said. "And honestly, I mean, the bottom line is, I'll be dead. So what do I give a s—?"

While legislative efforts to allow human composting in Pennsylvania have moved slowly, New Jersey is poised to be the next state to legalize the rapidly growing practice.

Legality varies from state to state

Human composting is one of the emerging alternatives to cremation or burial that are viewed as more environmentally friendly or more appealing than being burned to ashes through cremation (which uses fossil fuels) or lowered underground in a coffin (which can pollute soil).

The New Jersey legislature passed a bill legalizing human composting about a month ago with bipartisan support, in a 37-2 Senate vote and a 79-1 House vote. The bill is awaiting the signature of Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy, at which point the Garden State will become the 14th state to legalize the practice.

Human composting was first legalized in Washington state in 2019. Among Pennsylvania's neighboring states, New York, Maryland, and Delaware have all legalized the practice.

State Rep. Chris Rabb, a Democrat who represents parts of Philadelphia, is working on a bill to allow the practice in Pennsylvania.

Earth Funeral CEO Tom Harries said the company plans to open a facility in the region, potentially in Maryland, Delaware, or New Jersey, by early next year.

In the meantime, East Coast families are shipping their loved ones elsewhere — regardless of whether doing so is legal in their state. The method costs more and undermines the environmental benefit, Harries said, but it gives the option to people who like the idea of their body becoming soil until the industry expands.

Dianne Thompson-Stanciel, a New Jersey resident, had her husband's remains shipped to Washington earlier this year and now has his soil in plants around her home. She said she felt as if her husband, Kenneth Stanciel Sr., "came home."

"He'd been sick for a few years, so we spent a lot of time in the house together, talking all day long," she said. "This almost feels almost the same."

She said the option felt "more humane" than the alternatives, and the $7,000 total price tag was worth it to her.

"It's a comforting feeling for me to have that compost here," she said.

The average cost of a traditional full-service burial in New Jersey is over $9,000, and nearly $7,000 for a full-service cremation, according to consumer advocate Funeralocity. Direct cremation without a service, like a viewing, averages closer to $2,500.

How did human composting get started?

Katrina Spade, who invented modern-day human composting, is a 1999 Haverford College graduate and was awarded an honorary degree in March for her work. Spade founded Recompose, the first human composting company, in Seattle in 2017. The company began composting bodies in 2020.

Spade began pursuing the idea as a hypothetical as part of her master's degree thesis project while studying architecture at UMass Amherst. But as interest grew in the idea, she got the momentum to bring it to life.

"I wasn't hindered by the idea that I couldn't do it because I wasn't really expecting to make it into a business and an operating facility," she said. "But as I kept working on it, I realized, like, oh no, people really are craving something different when it comes to the end of life."

She said farmers had been composting livestock for years, so she "took that idea and designed it for a human and a human experience." Spade said her company serves East Coast families often and her goal is to open facilities around the country.

At least three other companies — the West Coast-based Earth Funeral and Return Home, and Minnesota-based Interra Green Burial — emerged after Recompose. Spade isn't bothered by that.

"At first I was pretty surprised to see it happen so quickly," she said. "It indicated to me that there was a real business model behind this ... that was validating in a way."

Efforts to legalize human composting in Pennsylvania

Rabb previously sponsored a bill to legalize human composting in Pennsylvania in the 2023-24 legislative session, but it did not progress. He has been working on a revamped version that he hopes to have ready to introduce before the legislature reconvenes in late September.

The Democrat said he has to dispel misinformation about the practice "because there are a lot of strong feelings about end-of-life matters."

"A lot of people are afraid of things that are new or new to them, and it's not because of the substance of that topic, but because of the newness, and that is sometimes disorienting to some people," he added.

A separate bill from State Rep. Mary Jo Daley (D., Montgomery) to legalize alkaline hydrolysis, or a water-based cremation, has bipartisan support but has not yet been voted on by either chamber.

Nancy Goldenberg, the president and CEO of the Philadelphia-area Laurel Hill cemeteries and funeral home, supports legalization of both practices because she believes people should have the choice about how to dispose of their body.

Plus, it's "good for business," she said.

"States that offer the widest range of choice are states where people will gravitate to ... and we've seen that happen," she added. "If it's a product somebody wants, they will travel to get it."

© 2025 The Philadelphia Inquirer. Visit www.inquirer.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC. ©2025 The Philadelphia Inquirer, LLC. Visit at inquirer.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments